MEXICO CITY, Nov 17 (Reuters) – Under pressure to increase production, Mexico’s state oil company Pemex has risked fines for violations that cause environmental damage rather than delay output to fix the underlying issues, according to two senior company sources.

The decision by Pemex to opt for fines instead of repairs represents a major blow to the oil regulator’s struggle to rein in the company, an energy behemoth closely tied to the government.

Over the past year, the regulator has fined Pemex four times for not complying with its own development plans for two top fields – Ixachi in Veracruz and Quesqui in Tabasco – that resulted in huge amounts of natural gas being burnt off.

In addition to a waste of resources, flaring releases greenhouse gases that contribute to climate change.

The two most recent fines could each reach 120 million Mexican pesos ($6.2 million), said a third source at the regulator with direct knowledge of the matter.

While relatively small, it would be the highest single fine ever levied by the regulator, locally known as Comision Nacional de Hidrocarburos (CNH).

Neither the amount of the two new fines nor the internal discussions about them have been previously reported.

Unlike in other countries, fines in Mexico are not made public until the legal process is completed.

Pemex did not respond to repeated requests this week for comment while the regulator declined to comment.

One senior Pemex official told Reuters the fines for violations were worth it because the fines were “small” and the company needed to speed up output to meet President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador’s ambitious production goals.

Pemex said in October to investors that it had managed to reduce the time between discovery of a field and production from eight years to one year.

Pemex was already fined over 42 million pesos ($2 million) for violating its own development plans for Ixachi, Reuters reported in August. Reuters was unable to determine the details of the first fine for Quesqui.

The fines are small for a company that had revenues of more than $87 billion between January and September, buoyed by high oil prices .

The other source said they had witnessed senior Pemex executives agreeing in four meetings that took place since the start of the year that the company would prefer to pay the fines than make changes.

Lopez Obrador’s office declined to comment on the fines. In 2019 during a visit to Ixachi, the president talked about the urgency of boosting oil production.

“If we hadn’t intervened in time, falling oil production would have put us in a situation of a lot of risk: it would lead – possibly – to a severe economic and financial crisis,” he said.

Pemex is appealing all four fines, according to two sources at the regulator. Reuters could not determine how long it would take to resolve the violations or how much it would cost.

Since February, neither Pemex nor the energy ministry have responded to repeated requests for comment about excessive flaring.

The company’s willingness to invite fines rather than resolve its flaring problems underlines structural problems around the regulation of Pemex, which faces mounting scrutiny from its own increasingly environmentally conscious investors to clean up its operations.

Mexican law stipulates that the oil regulator can only levy fines for breaches of development plans rather than for environmental damage.

A separate environmental regulator, whose head and key members are appointed by the president, is tasked with policing environmental harm but has historically not taken action against Pemex for flaring. Environmental agency ASEA did not respond to a request for comment.

WORDS VS ACTIONS

Pemex’s approach conflicts with the rhetoric of Mexican leaders, who are meeting with their global counterparts at the U.N. COP27 summit this week to discuss how oil and gas companies must accelerate the transition toward a low-carbon economy.

Recently, Pemex said it would work with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to meet ambitious international commitments.

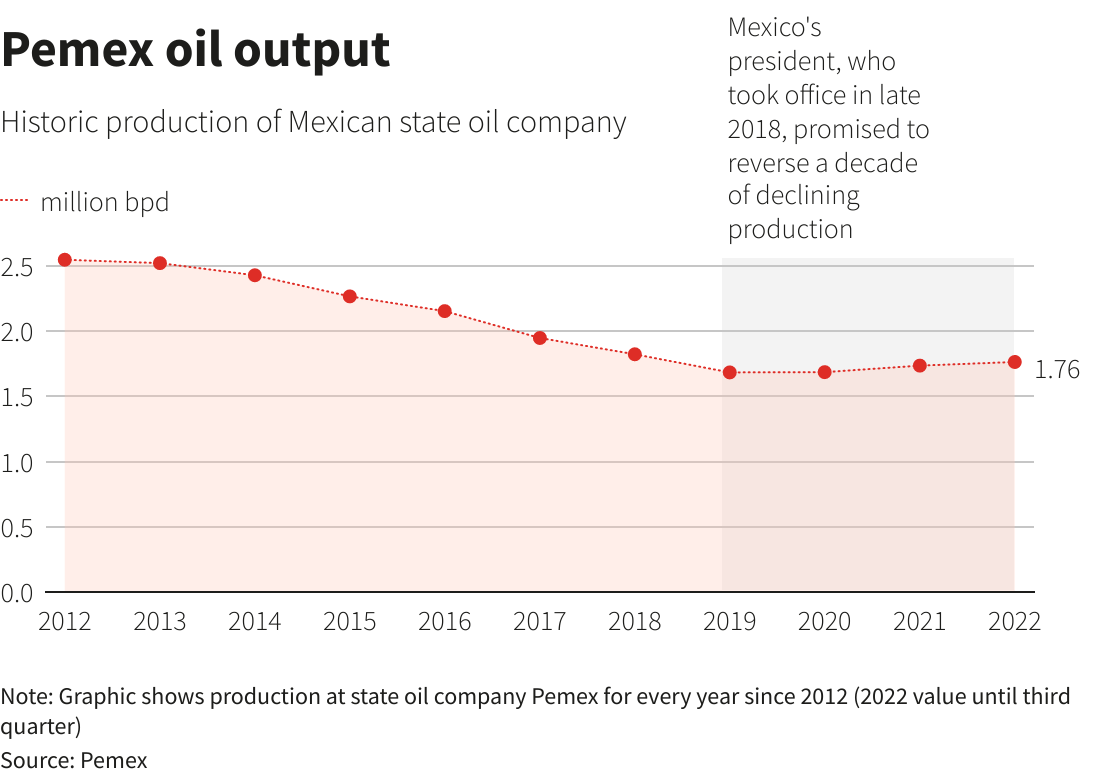

The world’s most indebted oil company, whose profits were for years plundered to fund government spending, has struggled to reverse a decade of declining oil production.

In Mexico, fines are decided by various factors including if it is a first or repeated offense, and damage caused.

Fines are low to avoid depleting Pemex funds that could be used to resolve the underlying problems, the sources at the regulator said.

Gas is often burnt off when it comes to the surface as a byproduct of oil exploration and production; but in the cases of Ixachi and Quesqui the gas is not a byproduct but rather one of two key resources, the other being higher-value condensate.

($1 = 19.3812 Mexican pesos)

Reporting by Stefanie Eschenbacher and Ana Isabel Martinez in Mexico City; Additional reporting by Adriana Barrera in Mexico City and Sabrina Valle in Houston; Editing by Stephen Eisenhammer and Lisa Shumaker

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles.