July 25 (Reuters) – The U.S. economy may ultimately skirt a recession, but it’s felt like one for months at Jon Ferrando’s 103 RV dealerships.

Retail sales of recreational vehicles are on track to be the lowest since 2015, said Ferrando, CEO and president of Fort Lauderdale, Florida-based Blue Compass RV, which operates in 33 U.S. states. There’s “definitely a recession in RVs,” he said.

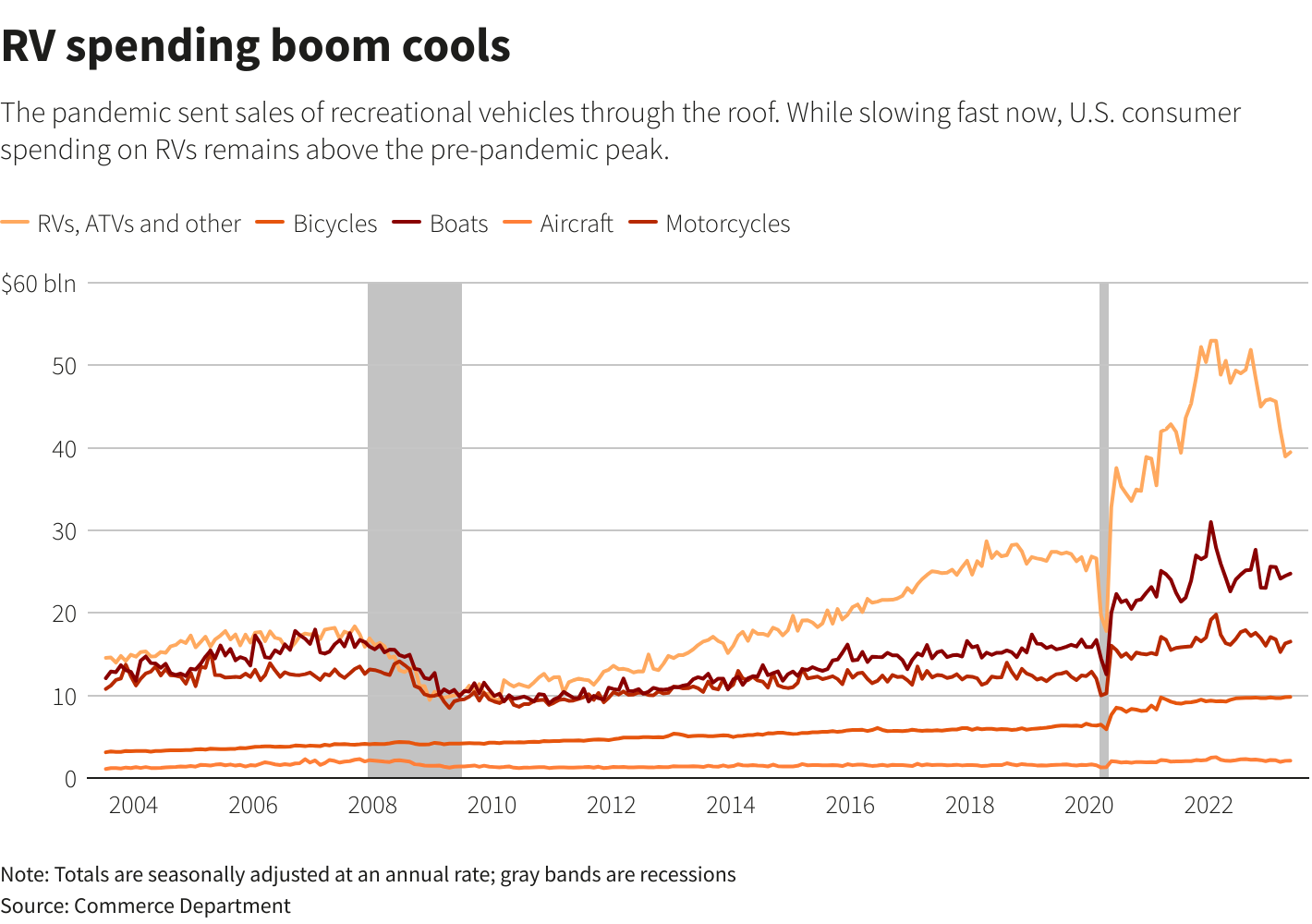

Blame the coronavirus pandemic. Few industries better illustrate the wild shift in U.S. spending habits that occurred during the health crisis.

In a matter of months, consumers stuck at home cut spending on services, as restaurants shuttered and airports turned into ghost towns, and began splurging on goods, especially items like RVs, bicycles, and swimming pools. Anything that made quarantine conditions more tolerable saw a massive surge in demand.

Winnebago Industries (WGO.N) CEO and President Michael Happe has called it the “COVID retail frenzy” when speaking to investors.

But trouble emerged soon after pandemic restrictions were eased and U.S. interest rates began to rise. The Federal Reserve has hiked borrowing costs 10 times since last March as part of an aggressive campaign to tame high inflation. The U.S. central bank’s benchmark overnight interest rate has climbed by 5 percentage points to the 5.00%-5.25% range, the highest level in about a decade-and-a-half.

The interest rate consumers pay on loans is well above even that, and RV loans recently have averaged around 10% versus 7% or so before the Fed’s monetary tightening kicked into high gear, Ferrando said. With 80% of his company’s customers financing their purchases, it was natural that rapid rate hikes would curb buyers’ appetites.

‘SCREAMING RECESSION’

As demand evaporated, manufacturers hit the brakes. North American shipments of new motorhomes and trailers, almost all of which are produced in the United States, are expected to plummet to 300,000 this year, about half the number shipped in 2021, according to the RV Industry Association. The only other time shipments have fallen so sharply was during the 2007-2009 financial crisis and recession.

Winnebago and Thor Industries (THO.N), the largest U.S. RV manufacturer, declined to discuss how they are adjusting to the slump, but investors seem to think the worst is over. Shares of Elkhart, Indiana-based Thor and Eden Prairie, Minnesota-based Winnebago are up about 46.5% and 29%, respectively, on a year-to-date basis.

“Our industry has always been a little challenged on forecasting around demand,” said Jason Lippert, CEO of LCI Industries, a large supplier of parts to the RV industry that is also based in Elkhart.

That shortcoming was magnified during the pandemic, he said. “During COVID, dealers would take whatever they could get – as long as it was an RV.”

Downturns in this business have long been considered a dependable recession gauge, but that may not apply this time.

“If I was just looking at RV data, I would be screaming recession,” said Michael Hicks, an economics professor at Ball State University in Indiana who tracks the industry, adding that pullbacks in RV shipments have signaled every U.S. recession since 1981. But the glut created by a rare event like the pandemic may have skewed the normal picture, he said.

RVIA spokesperson Monika Geraci said the industry faces a dual challenge: inflation has led to higher sticker prices and higher interest rates have made it costlier to finance hulking purchases like RVs.

“We expect in the second half of this year shipments (of RVs) will start to increase again,” Geraci said. The RVIA projects that shipments in North America will rebound to about 350,000 units next year “as consumers get more comfortable with the leveling off of inflation and the level of interest rates,” she said.

OLD AND OVERPRICED

The problem for many dealers is the unsold RVs on their lots. Gregg Fore, an RV industry consultant who previously ran an RV parts supplier, said half the new inventory at some dealers he works with are 2022 models. That figure would normally be about 20% to 25%, he said.

Dealers now face the prospect of bringing onto their lots the newest 2024 models which cost less than these aging models. “How do you sell a ’22 that’s more expensive than a ’24?” Fore asked.

Meanwhile, other sectors that saw pandemic-related booms have also fallen to earth – though in many cases not as hard as RVs.

Tyler Hermon, vice president of sales and marketing at Pools of Fun, a large in-ground pool builder in Indiana, said his backlog of orders for new pools is down to about three months – compared to the year-long waits that customers saw at the height of the pandemic.

“I would say we’re still, volume-wise and revenue-wise, ahead of where we were pre-COVID – so we haven’t fallen completely back,” he said.

Back at Blue Compass, there is also optimism. The company moved quickly to sell off the glut of older RVs on its lots, Ferrando said, and its service business has stayed strong as existing customers continue to need repairs and upgrades.

“There’s still interest in RVing,” he said, “but customers are just more cautious right now.”

Reporting by Timothy Aeppel;

Editing by Dan Burns and Paul Simao

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles.