The Netherlands offers a real-world test of what happens when flexible platform work becomes fixed employment. In 2025, Uber Eats couriers moved to employee status through staffing agencies — and the results were stark. Active courier numbers plunged as many work opportunities disappeared or workers simply walked away. Six months after the shift, only 10% remained on the platform, compared with 50% retention under the independent model a year earlier.

The Dutch case highlights a central dilemma: how to protect workers without eroding the flexibility they value most — and shows what’s at stake when that balance tips too far.

The shift to employment

The shift followed a 2023 Supreme Court ruling against a competitor, which heightened the likelihood that couriers would be classified as employees in the country. In response, Uber Eats tested an employment model in early 2024, closed new independent-contractor sign-ups in July, began the transition in December 2024, and completed it by mid-2025.

Under the new system, couriers are employed through third-party staffing agencies, paid hourly, and offered shifts of 3 to 5 hours that can be canceled up to an hour in advance. With no minimum-hour requirement, they can work only during scheduled slots, earning a fixed rate per hour regardless of the number of deliveries completed — a major change from the previous model, in which they could go online at any time.

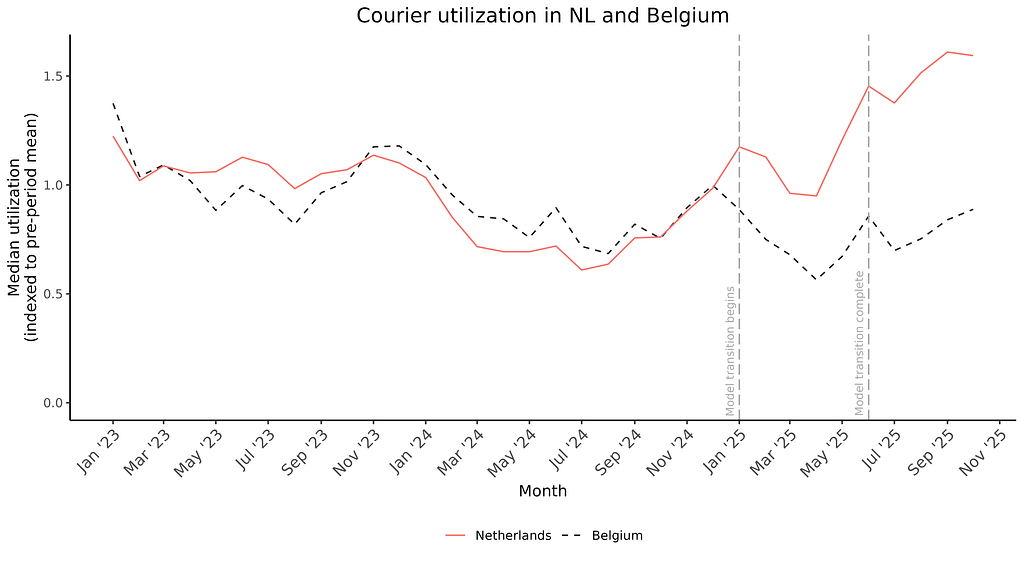

Paying couriers for time rather than per delivery requires tighter operational oversight. Courier coordinators monitor scheduling, performance, and attendance, issuing warnings or dismissals for repeated issues. This stricter management increases courier utilization — the share of time spent actively delivering — which rose sharply in the Netherlands compared with Belgium.

As the nature of the work changed, many couriers chose not to transition. Among those active before the model change in December 2024 — just prior to the transition — only 10% remained on the platform six months later, compared with 50% retention the previous year. In Belgium, where the independent contractor model remained in place, retention held steady.

Unfortunately, the business (along with restaurants and eaters) suffered. While Uber Eats’ performance management ensures couriers are now delivering more per hour, courier supply hasn’t met delivery demand since the model change. There continue to be many vacancies and, despite active recruitment efforts and a €750 sign-on bonus, it remains challenging to find workers willing to work as employees.

Why many couriers decided not to become employees

To understand why so many couriers walked away, Uber ran a call campaign reaching nearly 500 couriers, most of whom chose not to transition. Their responses revealed the loss of flexibility as a recurring theme across different concerns.

- Real-time access: Couriers said they could no longer go online whenever they wanted and faced new shift constraints. “As IC, I could work 24/7 when I wanted. With the staffing agency, I can’t. What if I want to work but I’m not scheduled? Then I just stay home.”

- Combining with other activities: Many felt unable to combine Uber with studies or other jobs. “I can’t work with Agencies because I already have other contracts. I can only work in my free time”

- Preference for other platforms: Some preferred to continue working with freelance apps that still offered independence. “I don’t think I’ll switch to the agency model, I have other freelance platforms.”

Among those who transitioned, only a small number valued the guaranteed hourly pay. Most echoed the same concerns about flexibility — now as lived experience. Many also viewed the necessary performance oversight as undesirable, saying they “couldn’t reject trips” or disliked penalties for lateness and missed shifts.

Lessons and reflections: balancing protection and flexibility

Protecting workers and preserving flexibility must go hand in hand. Replacing flexibility with fixed employment hurts workers, restaurants, and customers alike, and these dynamics aren’t unique to the Netherlands. The same trend played out in Geneva, where reclassifying couriers as employees led to steep declines in active couriers and deliveries.

But the lesson from the Netherlands is not that regulation is unnecessary — it’s that the design of regulation matters. Around the world, governments are exploring ways to extend protections while preserving the independence that platform workers value most. New frameworks in California, Washington, France, Greece, Estonia, and Australia maintain independent status while introducing minimum earnings, sick leave, and insurance. Others, such as India and British Columbia in Canada, offer proportional protections that scale with hours worked.

These examples show that smart, balanced solutions are possible — ones that protect workers without dismantling flexibility. Uber remains committed to working with governments and workers to design models that safeguard both: protections and autonomy.

From Flexibility to Employment: Lessons from Uber Eats in the Netherlands was originally published in Uber Under the Hood on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.