With the 2018 World Cup in full swing, Carlos Ghosn, chairman of the Renault-Nissan-Mitsubishi Alliance, has plenty to be optimistic about. Born in Brazil’s tin mining town of Porto Velho, raised in Lebanon and schooled in France, and as boss of a Franco-Japanese auto conglomerate headquartered in the Netherlands, he has a number of teams to support in the coming tournament.

“I support the winner,” Ghosn said when asked his preference.

Ghosn is best known for his turnaround of Nissan Motor, instrumental to the creation of the most successful merger in the global auto industry. In person, Ghosn manages to be both enigmatic and forthright, smoothly pivoting a conversation from topic to topic – a talent that would have been a key element in his survival. In his autobiography, he wrote that he always had the feeling of being different, from the outside, presumably making it easier to adapt to new environments.

Just as much as Ghosn loves numbers, targets and deliverables, he also points to the intangibles: “You need for people to give you the ability to deliver,” he said at a recent interview with the South China Morning Post. “They need to feel that you are part of them, you are part of their culture, you are connected to them, their identity, that they are not afraid of you, and that what you propose fits their goals.”

Yet, the bottom line is always paramount. “You have to understand the importance of identity, but at the same time, you have to overcome it by understanding that there are some things that need to be done. But you don’t do more than is necessary, and it’s only for business purposes.”

It is like walking a tightrope between the needs of a corporate culture, often rooted in a national culture, and those of a business. “I don’t like it when people talk about a global leader as someone who went to school in Brazil or likes Thai food,” he said. “By definition, a global leader is someone who can deliver performance anywhere and everywhere. That’s a global leader. You can’t have a global leader who can’t motivate elsewhere (outside his or her own country).

Ghosn’s rise to corporate power is underlined by a series of rapid turnarounds. Educated by Jesuits in Lebanon and trained as a chemical engineer at the prestigious Ecole Polytechnique and Ecole Des Mines in Paris, he was said to excel as a student. He took a job as management trainee with French tyre maker Michelin in 1978, and quickly rose through the ranks.

By definition, a global leader is someone who can deliver performance anywhere and everywhere

Carlos Ghosn

In 1985, he returned to his home country to oversee Michelin’s Brazil operations. At 31, he took charge of manufacturing operations for South America at a time of massive inflation (over 200 per cent in 1985) and financial turmoil.

Ghosn, whose surname rhymes with “bone,” succeeded with a method that he has employed repeatedly: setting up troubleshooting teams, often mixing French and Brazilians, to come up with solutions. The operation was back to profitability within two years. He went on to run Michelin USA in 1989, and in just two years, engineered the takeover of troubled US tyre maker BG Goodrich.

In 1996, Ghosn was recruited to Renault by CEO Louis Schweitzer, who had started a revamp programme , which included cutting the French government’s stake in the struggling French carmaker from 80 per cent to 16 per cent.

As executive vice-president in charge of operations, Ghosn had derided Renault’s corporate culture as a talking shop, and so went about cutting costs, which earned him the moniker, Le Cost Killer. It was a nickname he hated, according to John Harris, Ghosn’s speech-writer for four years.

Schweitzer apparently knew the potential he had in Ghosn, and in March 1999 paid US$5.4 billion to cover Nissan’s debt in exchange for a 36.6 per cent stake in the ailing Japanese carmaker. That same month, Schweitzer asked Ghosn to lead the turnaround at Nissan.

The task was enormous. Nissan was plagued with enormous debt and excessive production capacity, had not invested in new models due to cash flow problems and had investments tied up in its many suppliers – part of the Japanese Keiretsu industrial system. Freeing up capital by dumping unproductive investments, cutting costs and workers, and bringing in new, often foreign, talent were assaults on the cornerstones of Japanese corporate culture.

“I knew that if I tried to dictate changes from above, the effort would backfire, undermining morale and productivity. But if I was too passive, the company would simply continue on its downward spiral,” Ghosn wrote for Harvard Business Review in 2002. He reportedly gave himself a 50 per cent chance of success.

Ghosn cut 20,000 jobs – 8.5 per cent of Nissan’s workforce – in an unprecedented move in a nation that rewarded loyalty with lifetime employment.

Following methods honed over years of executing rapid turnarounds, Ghosn established nine cross-functional teams to develop the Nissan Revival Plan. “I had used [cross functional teams] in my previous turnarounds and found them a powerful tool for getting line managers to see beyond the functional or regional boundaries that define their direct responsibilities. In my experience, executives in a company rarely reach across boundaries,” Ghosn wrote in 2002.

“Getting Ghosn in was like having a prostate exam for corporate Japan; they knew it was sensible, healthy and necessary, but it was still an indignity. They realised they had to endure. And the result was that he brought the company back to life,” said speech-writer Harris.

To a highly sceptical Japanese public, Ghosn spoke out frequently about the financial necessity of remaking Nissan. A return to profit helped. The turnaround cemented Ghosn’s position, not just within the newly combined Renault-Nissan alliance.

As Ghosn’s reputation went from outsider to business saviour, a Japanese bento (lunchbox) was designed in his honour, and he also became the subject of a series of manga – adult-themed comic books.

“We started work on the series after it was evident the depth Mr Ghosn’s impact was having on the company and, more broadly, on companies in Japan. And we could see that after the V-shaped recovery at Nissan was visible,” said Akihiro Yoshino, the editor at Shokgakukan, publisher of The True Story of Carlos Ghosn series, who had interviewed Ghosn extensively.

Yoshino said the Japanese focus on relationships took a rough hit in the Ghosn years, but the impact had been far-reaching. “It did forge a path that has taken Japan away from the local ways of doing business to make companies more competitive internationally.”

Just two years after joining Nissan, he became CEO in 2001, and in 2005, the chief executive of Renault, making him the first person to head two Fortune 500 companies.

We started work on the series after it was evident the depth Mr Ghosn’s impact was having on the company and, more broadly, on companies in Japan

Akihiro Yoshino, Shokgakukan

In 2006, Renault-Nissan even considered extending their partnership to General Motors, then in serious financial trouble. The deal didn’t happen, but GM shareholder-activist Kirk Kerkorian originally pressed Ghosn on opening the alliance to GM on the strength of his reputation as turnaround artist.

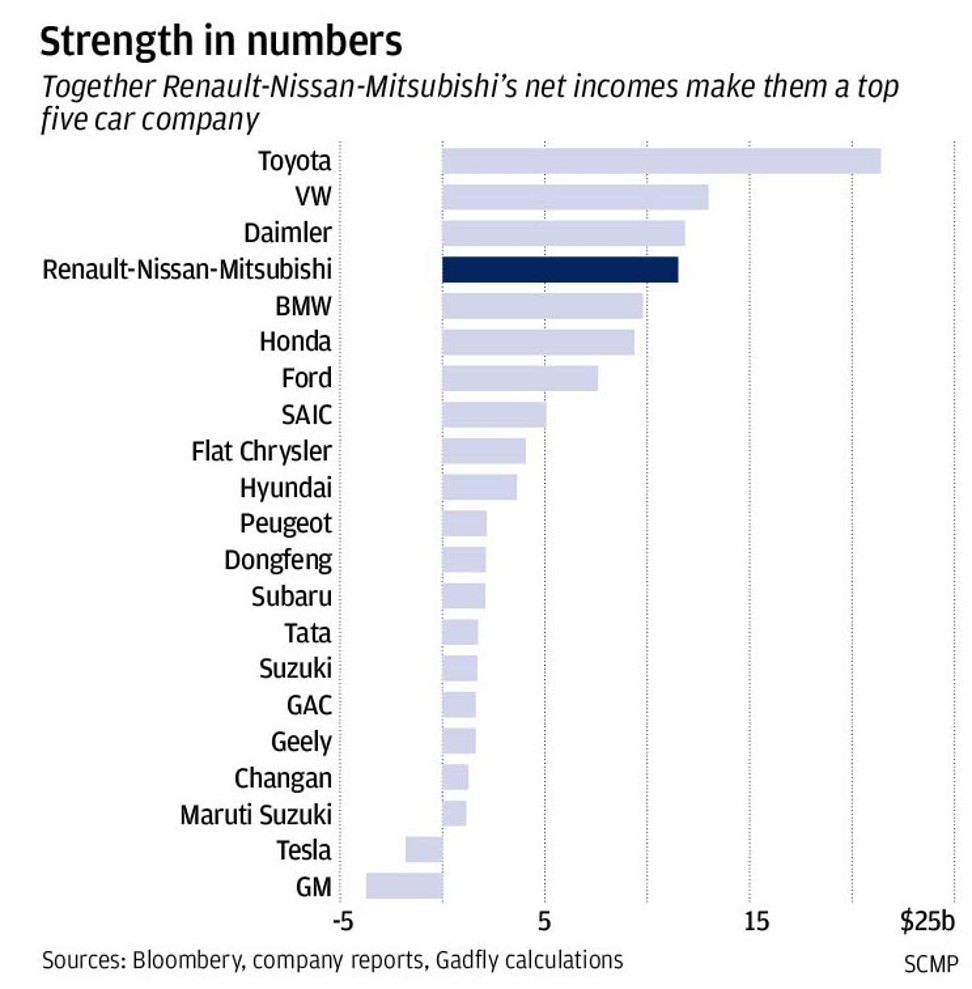

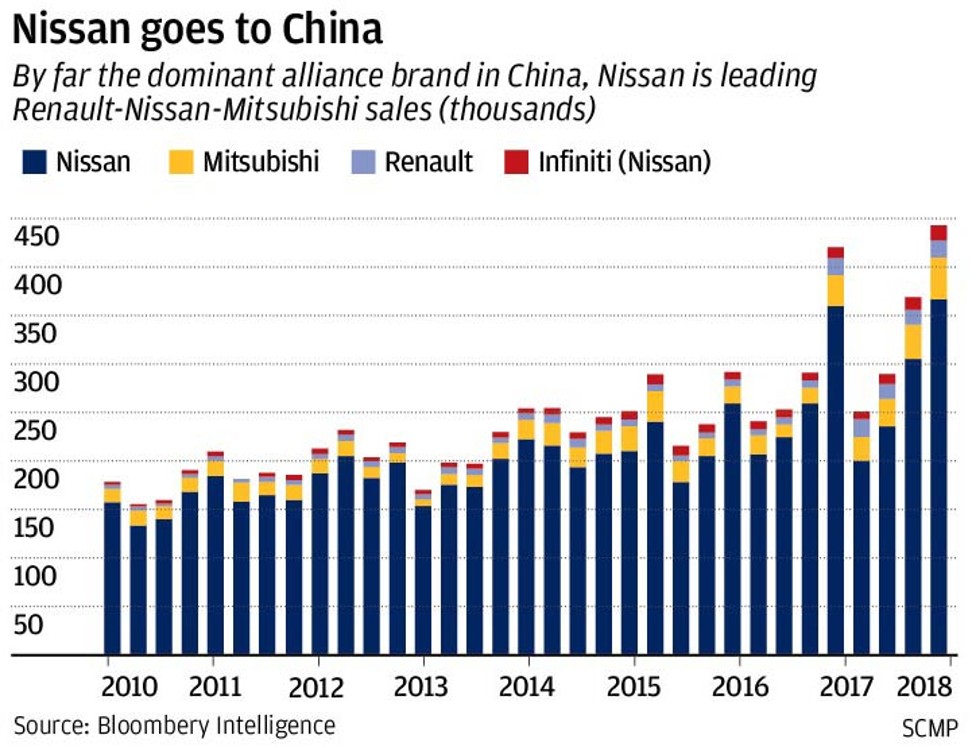

In 2016, Mitsubishi Motors joined the Renault-Nissan partnership, which created the Alliance, one of the world’s largest carmakers and a tripartite corporate entity through a complex cross-shareholding structure.

Ghosn likes to say that the next five years will see as much change as in the last 50. The list of disruptions hitting the auto industry is long. Electric vehicles (EVs), while still a fraction of the overall market, are mandated by governments around the world, particularly in Europe, China and India. The growing performance parameters of EVs and public acceptance of them have led to the establishment of electric carmakers like Shenzhen-based BYD and most famously, Tesla.

Accustomed to challenging circumstances, Ghosn describes the landscape as “an exciting time for the industry”, where the battle is not just about competitiveness, but also the attractiveness of the kind of services – encapsulating developments in technology, engines and applications, and imagination – carmakers can offer. This is why, Ghosn says, he talks to many tech companies, including Nvidia, for partnerships that he reckons would become the mainstay of the industry.

Ghosn has positioned his firms at the forefront of electronic vehicles, bringing to market the Nissan Leaf in 2010.The 2018 edition, which launched last September, aims to beat off criticisms of the car’s earlier editions, and has been compared favourably with the much anticipated Tesla Model 3.

The Alliance is now the world’s leading EV maker: Renault has a significant line up of EV models, and Infiniti – Nissan’s luxury brand – will be all-electric by 2021. It developed a platform for EV technology that all the companies work from.

The keys to it all, Ghosn says, are governments. “We are moving towards electric cars … the technology is headed there through better motors and knowledge. But I think the main driver is the regulation, not the consumer; it’s how much governments will support it. China, we know, will give full support.”

Ghosn, once the wunderkind of industry turnarounds, turned 64 in March, making it reasonable to wonder how the Alliance will continue without him. Based in Amsterdam, it is an entity that includes three carmakers, as well as a stake in Russian carmaker Avtovaz and a partnership with Dongfeng Motor to build EVs for the China market.

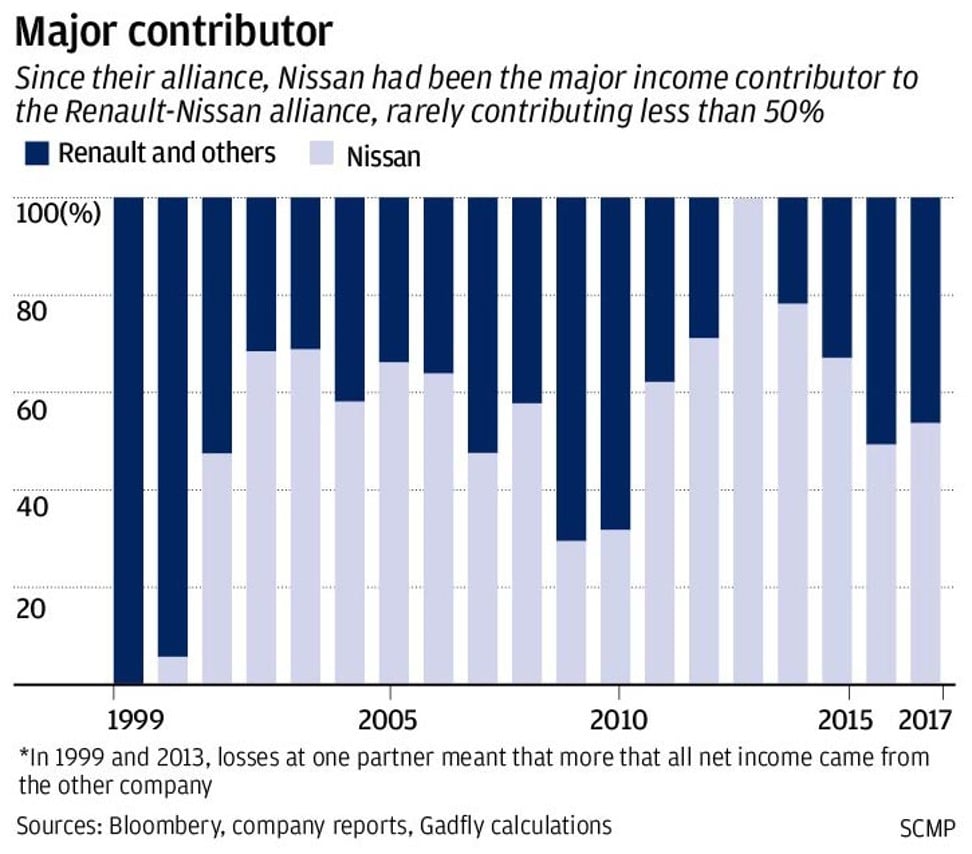

The real test is streamlining the lopsided two-decade old Renault-Nissan alliance (with Mitsubishi added since 2016). Nissan owns 15 per cent of Renault with no voting rights, but contributes the bulk of vehicle models, sales and profit to the alliance. Further complicating matters, the French government which owns another 15 per cent is the biggest shareholder. Conversely, Renault owns 44 per cent of Nissan and can vote on corporate matters. It’s a relationship that will involve as much as government-to-government negotiation between Paris and Tokyo to manage, as it is with two corporate boardrooms.

Ghosn, who put the entity together, is still the lynchpin; he is chairman of all three carmakers, as well as CEO of Renault.

Last September, the Alliance announced its six-year, 2022 plan, with integration targets that include producing nine million vehicles built on four common platforms and raising the proportion of common power trains from one-third to three-quarters of total volumes. New technology in EVs and autonomous driving are also expected to drive synergies.

Four months before that, Ghosn turned over the Nissan CEO role to Hiroto Saikawa, who in a recent interview with the Nikkei Asian Review, made clear his opposition to further integration with Renault.

And successors can also turn into competitors. In 2014, Renault COO, Carlos Tavares, left the company soon after he let it be known that he’d never be CEO if he had stayed on.

Ghosn says that his main job is now operating as chairman of the Alliance. “In a certain way, it’s an evolution to position yourself as the head of the Alliance, to help each CEO prepare.”

Whether Ghosn can find a successor, one able to walk the tightrope that he built, is a growing challenge as the world’s biggest carmaker faces a litany of challenges.

With additional reporting by Julian Ryall in Tokyo

(The full version of this article is published in the June issue of The Peak magazine, available at selected bookstores)