Related News

Video installations from ‘Stille Bewegungen/Tranquil Motions’.

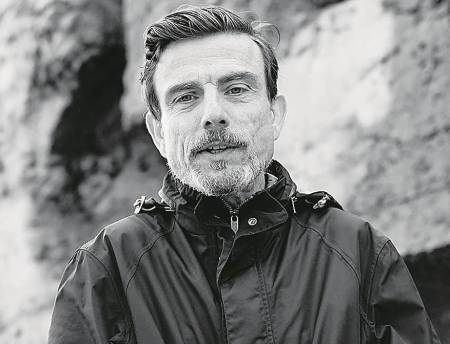

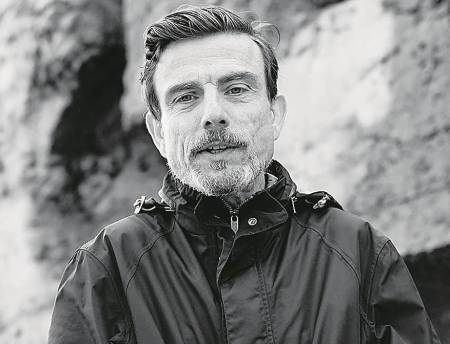

Engaging with the works of Marcel Odenbach demands attention and complete immersion. The 65-year-old’s oeuvre — considered pioneering in German video art — explores the difficult themes of migration, social repression of minorities and creation of conventional gender roles, while also reflecting on the nature of the medium itself. The exhibition ‘Stille Bewegungen/Tranquil Motions’, which opened at the National Gallery of Modern Art, Mumbai along with Goethe-Institut/Max Mueller Bhavan Mumbai, last week, offers a glimpse into the last 30 years of Odenbach’s career, featuring early works that were created to be viewed on monitors, complex installations with large projections as well as paperwork featuring his distinctive collages. The exhibition is curated by Matthias Muhling for the Institut fur Auslandsbeziehungen (ifa). Excerpts from an interview:

Advertising

Marcel Odenbach

A striking feature of your video works is the use of sound. How do you bring together the visual and aural elements in your work?

Right from the beginning, even in the early pieces where I did the sound by myself, I was giving the same attention to it as to the image. I also learned a lot from cinema, especially (Alfred) Hitchcock, about how much you can influence image by the use of sound. And my pieces are like collages, so sound-wise also, they are like collages. For example, for the images, I collect archival footage, images from magazines etc, and I work with sound in the same way.

Would you call Hitchcock an influence?

Hitchcock was an influence in a way. A lot of his work actually deals with the question of voyeurism, and the first time that I ever handled a camera, I also felt like a voyeur. I was looking at people and situations through my camera, and that gave me a certain distance from reality.

Why was that distance important?

Advertising

In my early days — and this has a lot to with my autobiographical details — I was travelling a lot, meeting different people, and experiencing different cultures. Looking at these through a camera helped, because the distance ensured that these experiences wouldn’t overwhelm me with directness.

Could you elaborate on how your autobiographical details influenced your view of the world?

I suppose it has to do with the fact that I was born more or less directly after the Second World War when Germany was looking inwards. Also, I come from a very international family. My father was born in Holland, one grandfather was born in France and grandmother in Belgium. I have family in Congo, and a Jewish family too, which had to leave the country. There are a lot of refugees in the family. So travelling and trying to find your identity was a constant in my childhood.

When you began making videos in the ‘70s, did you follow any models?

Popular Photos

The earliest video artists were actually visual artists first. They didn’t come from the cinema. But I was interested in bringing together films and video art, so on the one hand, my heroes were some of the earliest American video artists like Vito Acconci, Bruce Nauman, and of course, Nam June Paik. On the other hand, there were also filmmakers like Jean-Luc Godard who were working with film in a completely different way, compared to commercial cinema.

More than any other medium, photography and video have developed the most rapidly. How did you adapt?

I used the new formats, but I was always critical. Nowadays everybody is constantly using images, but without reflecting what the image means. Fifty years ago, when people took photographs, they had to be far more selective about which images to make. Today’s selfie culture has changed all that.

What does that mean for an artist? Does your approach change as well?

As an artist, the decisions you make about images are always very private and you’re constantly in a critical confrontation with the image or the sound. This means that you’re constantly questioning the choices that you make, about the colour, or the edit or the frame. I do this questioning because I have to reflect myself in the work. This is very different from somebody running around making selfies. At least, I hope so.

What is the most important step of your art-making process?

You have to learn to get rid of the image that you love the most. For example, when I did In Still Waters Crocodiles Lurk, a piece about the genocide in Rwanda, I had 29 hours of material. I decided that it shouldn’t be longer than 40 minutes, and I had to learn to get rid of things. You have to learn to kill your babies.

Advertising

Did your paper works emerge from the videos or vice-versa?

When I started to do video, I tried to make storyboards. When you don’t have dialogues or a direct story, you have to work with images. So I would cut out images from magazines and newspapers, and would glue them together in a storyboard. This was how I started with collage, and you can see how they’re connected to my video works.

The exhibition is on at NGMA, Mumbai, till November 30.