Project to record cultural, geological and environmental treasures at risk from climate crisis

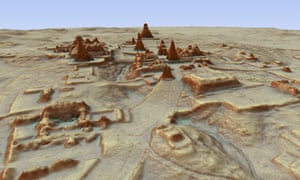

The Earth Archive plans to use Lidar, which has been used to reveal archaeological treasures such as the Mayan city of Tikal.

Photograph: Canuto and Auld-Thomas/AP

A project to produce detailed maps of all the land on Earth through laser scanning has been revealed by researchers who say action is needed now to preserve a record of the world’s cultural, environmental and geological treasures.

Prof Chris Fisher, an archaeologist from Colorado State University, said he founded the Earth Archive as a response to the climate crisis.

“We are going to lose a significant amount of both cultural patrimony – so archaeological sites and landscapes – but also ecological patrimony – plants and animals, entire landscapes, geology, hydrology,” Fisher told the Guardian. “We really have a limit time to record those things before the Earth fundamentally changes.”

He also said that while it was important to take action on the climate crisis, even if we started “living like the Flintstones”, changes are already taking place.

The main technology Fisher hopes to use is aircraft-based Lidar, a scanning technique in which laser pulses are directed at the Earth’s surface from an instrument attached to an aircraft. The time it takes for the pulses to bounce back is measured, allowing researchers to work out the distance to the object or surface they strike. Combined with location data, the approach allows scientists to build 3D maps of an area.

The method has already helped reveal ancient cities deep in jungles and map the full extent of sites built by rivals to the Aztecs.

The resolution of aircraft-based Lidar data can lead to images with stunning detail. “We can see things on the ground that are on the order of 20cm or so … which is about the size of a construction brick,” said Fisher.

Fisher said the idea to use Lidar to create a global map came to him after hearing of the work of CyArk, a non-profit organisation which uses digital techniques including laser scanning to record cultural monuments and sites in 3D.

“I came to realise that is great, but those archaeological sites are just a tiny fraction of what we are actually about to lose in the next couple of decades because of the climate crisis,” he said.

Fisher said that Lidar works well over land and the ice caps. As a result the project will focus on the planet’s land area: roughly 29% of the Earth’s surface. Fisher says the first areas to be recorded will be those most under threat, such as coastal regions at risk from sea level rises and the Amazon, where deforestation is surging under the Bolsonaro government in Brazil.

Fisher said the first move was to collate existing Lidar data. The Earth Archive will also contain data from other techniques including aerial photography and satellite data, some of which already exists.

The result, Fisher said, will be an open source record of the planet which could help archaeologists, geologists, conservationists and others.

Besides revealing manmade structures within jungles, Lidar can also reveal details such as the age and complexity of forests. The data can also be used to reconstruct landscapes and to track changes to the landscape over decades.

Building the Earth Archive will not be cheap: Fisher estimates it would cost about $15m (£12m) to scan much of the Amazon within two or three years.

He says a large part of the cost lies in getting the equipment to the required location, while filtering the data takes people power. While Fisher said the team was seeking funding, he said some organisations had already pledged to donate services in kind.

Fisher’s plans have had a mixed response from others in the field. While most say such a resource would be valuable, they say the practical hurdles are considerable.

Kevin Tansey, professor of remote sensing at the University of Leicester, welcomed the project, but said Lidar was expensive and time consuming. What’s more, changes in some areas are happening so quickly that landscapes could be altering drastically even as data is collected.

Prof Mat Disney of University College London raised concerns the project’s expensecould divert money away from other research. What is more, he added, getting permission to map certain areas could prove difficult.

“Who is going to give them permission to fly over Brazil? The Brazilian government aren’t,” he said.

Dr France Gerard of the Centre for Ecology and Hydrology also has mixed feelings.

“I think conceptually it is a great idea,” Gerard said. She added that many countries such as the Netherlands were already carrying out Lidar surveys.

However, Gerard has concerns over areas being captured at different points in time. “The date of the observations will vary tremendously across the globe,” she said.

Gerard said there were also questions about whether the raw data would be made available, and what sort of data would be collected.

Both she and Disney note there have already been space-based Lidar projects that offer consistent, global-scale data and are providing valuable information on forests, albeit at a far lower resolution than aircraft-mounted Lidar – this lower resolution is something Fisher says is problematic.

Fisher says his project will take time but will be valuable. “I won’t live long enough to see the results of this project, none of us will, and our kids won’t live long enough,” he said.

“It is for their grandchildren, and their grandchildren, and their grandchildren. [It’s like] the ultimate gift we can give to future generations.”