In a few weeks the California DMV will release disengagements data from Cruise and other companies who test AVs on public roads. This data is really great for giving the public a sense of what’s happening on the roads. Unfortunately, it has also been used by the media and others to compare technology from different AV companies or as a proxy for commercial readiness. Since it’s the only publicly available metric, I don’t really blame them for using it. But it’s woefully inadequate for most uses beyond those of the DMV. The idea that disengagements give a meaningful signal about whether an AV is ready for commercial deployment is a myth.

Our collective fixation on disengagements has been further fueled by the AV companies themselves. Many of them give demo rides that include a de facto story-line that goes something like, “I didn’t touch the wheel during this demo, therefore it works.” This is silly, and everyone knows it. It’s like judging a basketball team’s performance for the year based on how they looked during a practice session. Or winning a single spin of roulette and claiming you’ve beaten the house. A carefully curated and constrained demo ride is just the tip of the iceberg, and we all know what happens if we ignore what’s lurking below the surface.

The AV industry is in a trust race, so it’s important that we do things to build confidence in the technology. It’s certainly convincing to go on a ride where it seems the human is just there for show, or on rides where there’s no human present at all. So companies carefully curate demo routes, avoid urban areas with cyclists and pedestrians, constrain geofences and pickup/dropoff locations, and limit the kinds of maneuvers the AV will attempt during the ride — all in order to limit the number of disengagements. Because after all, an AV is only ready for primetime if it can do dozens, hundreds, or even thousands of these kinds of trips without a human touching the wheel. That’s the ultimate sign that the technology is ready, right? Wrong.

After extensive testing in complex urban environments, we’ve come to realize there’s a threshold of environmental complexity above which it’s nearly impossible for even a well-trained, attentive, and responsive human to avoid touching the wheel. Said another way, even if the AV was 100x better at driving than a human, rides through places like downtown SF will still regularly generate disengagements. As a result, disengagement-free driving is not actually a prerequisite for commercial deployment of AVs.

If an AV is functioning correctly, then why does the human take control? Sometimes things happen really quickly and sometimes there are many distinct but correct ways to handle a situation — each of these may lead to the human taking control of the AV out of caution. This would also be true if you secretly had a person driving an AV and told another person to supervise and take control if they ever felt the need. Have you ever been in the backseat of a human-driven car and felt the urge to grab the wheel when something crazy happens on the road? It’s exactly like that.

Let’s break down the common reasons for disengagements a bit more to understand how they can occur:

1) Naturally occurring situations requiring urgent attention

In complex urban scenes, it’s very common to require a split-second decision by the driver. People pop out from behind parked cars, drivers cut our AVs off at the last second, etc. Since Cruise’s top priority is safety, we instruct the driver to use their judgement and disengage if they feel it’s prudent, even if it turns out to have been unnecessary, and without penalty for doing so. We’ve put great care into designing our user interfaces so that it’s clear what the AV will do next, but sometimes things change too quickly for this to be effective in preventing a disengagement (whether it was necessary or not).

2) Driver caution, judgement, or preference

Humans aren’t perfect, sometimes a perfectly informed driver will misjudge a situation, even if they’re given accurate information about a decision the AV plans to make several seconds in the future. If they think the planned path is wrong or might be wrong, we instruct drivers to disengage. This can happen even for paths that are legal, comfortable, and predictable to other drivers. And even with a second driver actively monitoring the scene and various displays designed to convey the AV’s future intent.

3) Courtesy to other road users

We test on the streets of San Francisco, which is an extremely valuable way to quickly improve and validate our technology. We don’t take our responsibility to ensure that such testing is performed safely, respectfully, and responsibly for granted. So until our AVs meet our desired level of performance in all dimensions, we err on the side of politeness and allow our operators to disengage the AV system if they feel it’s confusing other road users. Or even if another driver is having a rough day and chooses to act aggressively. Again, safety first.

4) True AV limitations or errors

These are situations where the AV’s action or inaction may have led to a collision or other significant issue, and are sometimes reportable to the DMV. It’s physically impossible for AVs to avoid all collisions or interpret every situation exactly like a human driver would, but our AVs are improving rapidly and we’re not far off from beating the average human driver and ultimately achieving a level of safety performance substantially better than that of even the world’s best human drivers.

All this isn’t to say that disengagements should be completely ignored. Even if a disengagement occurred for a reason other than an AV error, it can still be important. In order to validate an AV’s performance in tough situations, we need to understand what the AV would have done after the disengagement in the absence of any human intervention. We use multiple ways to analyze data from disengagements. Sometimes it’s sufficient to examine what the AV was planning to do at the exact moment of disengagement, such as whether the AV was planning to stop or that it was correctly tracking an object in the distance.

In more complex or interactive scenes, we run simulations to examine what would have happened in another universe where the AV was operating in driverless mode instead. We use one of our simulation engines to forensically reconstruct the scene in as much detail as necessary to model the critical elements of the scene. We then fork reality at the time of disengagement and apply an AI model to other agents in the scene (cars, humans, bikes, etc.) to examine possible potential future outcomes in a highly interactive way that closely resembles what we’ve seen other people do on the road in the past.

We also use these same techniques to confirm that changes to our software have a positive impact on scenarios where we deemed the AV to be in error in the past. The net result is that every software release is at least slightly better than the previous one. In basketball terms, this would be equivalent to an athlete who never misses the same shot twice.

Fun stuff. But if we can’t use the disengagement rate to gauge commercial readiness, what can we use? Ultimately, I believe that in order for an AV operator to deploy AVs at scale in a ridesharing fleet, the general public and regulators deserve hard, empirical evidence that an AV has performance that is super-human (better than the average human driver) so that the deployment of the AV technology has a positive overall impact on automotive safety and public health. This requires a) data on the true performance of human drivers and AVs in a given environment and b) an objective, apples-to-apples comparison with statistically significant results. We will deliver exactly that once our AVs are validated and ready for deployment. Expect to hear more from us about this very important topic soon.

In the meantime, you can extract some limited signal from the CA DMV’s disengagement reports by looking at the rate of change for a company’s metrics, but this can’t really be used to compare one company’s absolute performance to another. Disengagement data isn’t adjusted for driving complexity, weather conditions, or other spatio-temporal variations between miles that affect difficulty (I wrote in the past about how all miles aren’t equal). Similarly, the mileage counts included in these reports tell you how much a company is spending on AV testing, but unfortunately that’s about it.

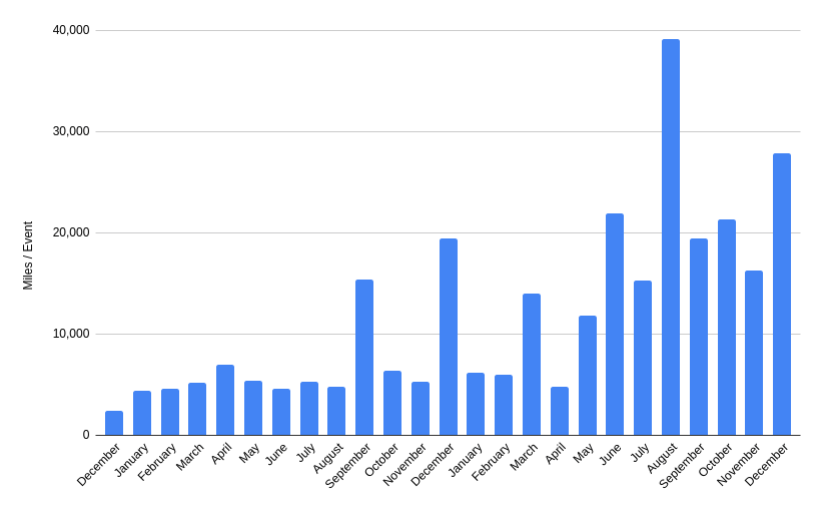

We believe customers will flock to the safer, cheaper, and more comfortable product, so we obsess about making our product better and better. There’s no obvious performance ceiling for AV performance — human performance certainly isn’t where we’ll stop — so rate of change in performance is perhaps the most telling metric for AV companies over the long run. In contrast, it isn’t really possible for human-powered rideshare services to make their product better, since driving quality is roughly equivalent across large pools of individual human drivers. The quality of the human-driven rideshare product is therefore essentially fixed, or may actually decline over time as rideshare companies exhaust the supply of the best human drivers. We think AV rideshare can be much, much better. Our DMV-reported data suggests we’re on the right trajectory so far:

Rate of improvement is one signal, but it’s still fairly abstract. A more qualitative indicator of technology maturity is video footage of actual rides. Look for a significant volume of raw, unedited drive footage that covers long stretches of driving in real world situations — this is hard to fake. Keep in mind that driving on a well-marked highway or wide, suburban roads is not the same as driving in a chaotic urban environment. The difference in skill required is just like skiing on green slopes vs. double black diamonds. If there are no disengagements, that’s even better, but even in complex environments this is a matter of both luck and skill. If there are disengagements in the video, look for evidence that they weren’t necessary.

Despite all the AV demos that have taken place over the years, the only video that I’ve found anywhere online that shows continuous, rideshare-like autonomous driving is the one that we posted back in early 2017 (slowed down version here). I haven’t seen any others that are more than a few minutes long. We’re certainly biased and have our own opinions, but I think one can assume that if anyone else had this level of performance, they’d be showing it. I’d like to see more of these, because I think they are one of the many things that will help us debunk the belief that AVs are only science projects.

Since that last video, our service area has expanded to cover the entire 7×7 region of San Francisco and we route to within less than a block of almost all addresses in the city. That means traversing crazy steep hills, narrow streets, and everything else needed for efficient routes and smooth rides. So we’re long overdue for some new videos. These don’t contain our most impressive maneuvers or the most obvious errors, but they do give you sense for how our AVs perform. These happen to be disengagement-free drives, because — let’s face it — it’s just really cool when that happens.

https://medium.com/media/bd147123331601c29e5f1c1855c7fc7e/hrefhttps://medium.com/media/21dfd7ec770ab5f93e1edcc86964ef43/href

Between the trends seen in our metrics and these videos, I think it’s clear we’re well on way to building and shipping a great AV experience. More details on this next week.

The Disengagement Myth was originally published in Cruise on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.