Remodelling the global alliance with Renault and Mitsubishi will be tougher

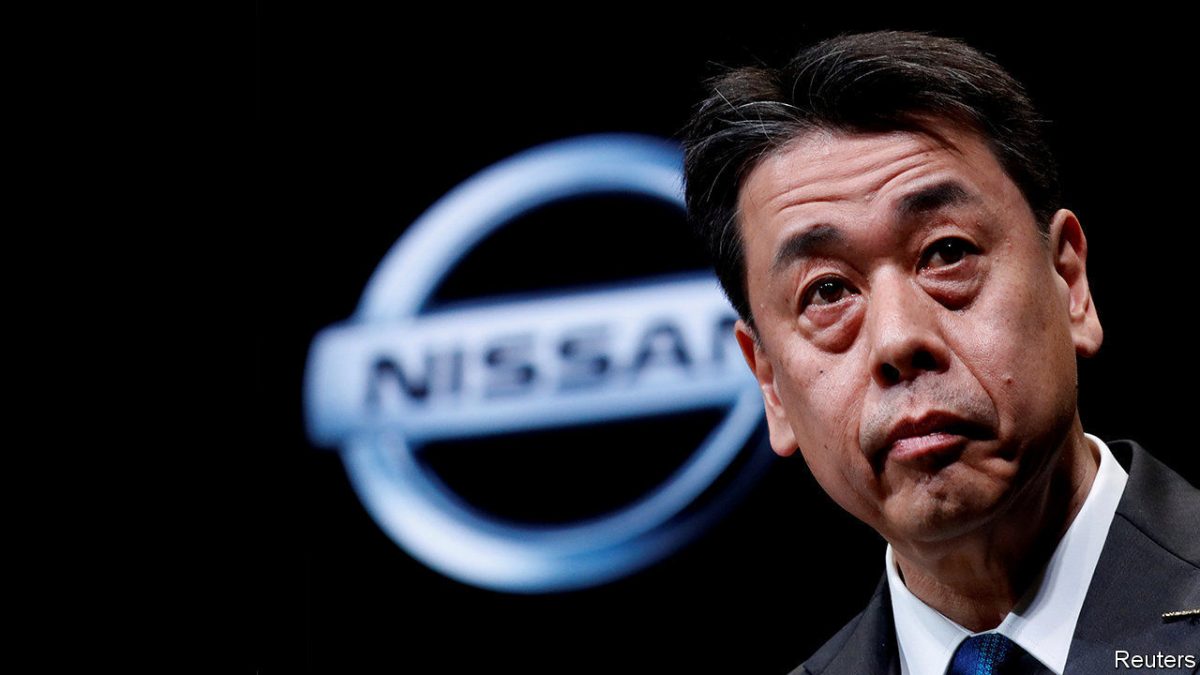

NISSAN IS IN for a makeover. On July 15th the Japanese carmaker will unveil what is rumoured to be a sleeker, more minimalist logo more in line with the contemporary aesthetic. To its boss, Uchida Makoto, the redesign is the outward expression of deeper corporate reinvention after a turbulent period. He wants to streamline not just the marque but Nissan, too, as a smaller, more efficient concern. The new vision, first unveiled in May and reiterated in a recent interview with The Economist, will not be easy to bring about.

Until 2017 Nissan was racing ahead. That year it sold 5.8m vehicles and raked in an operating profit of $5.2bn. Its alliance with Renault of France and Mitsubishi, another Japanese firm, overtook Germany’s Volkswagen to become the world’s biggest carmaker, selling a grand total of 10.6m sets of wheels.

Then things took a turn for the worse. Nissan fell short of targets in America, one of its biggest markets. Chasing volume with ageing models forced heavy discounting, irritating dealers and sullying Nissan’s reputation. A costly push into emerging markets failed to pay off as economies in Brazil and Russia soured. Car sales in China, hitherto a reliable growth market, slumped. The alliance, always fractious, nearly collapsed after its chief architect and chairman (as well as boss of Renault), Carlos Ghosn, was arrested in late 2018 on charges of financial misconduct.

As a result of all this, Nissan’s revenues dipped in 2018, then again in 2019. Its share price fell by nearly half over the two-year period. In the latest fiscal year to March the company booked an operating loss of $380m.

Enter Mr Uchida. He took over as boss in December after his predecessor, embroiled in the Ghosn scandal, was forced out. Half a year into his stint he cuts a relaxed figure, at least by the standards of corporate Japan. What he lacks in Mr Ghosn’s brashness he makes up for in quiet focus.

His downsizing plan looks both wise and achievable. Closing factories in Spain and Indonesia and cutting production will reduce capacity by 20% to 5.4m cars a year. The target of slashing costs by $2.8bn in total by 2021 appears within reach.

Restoring a tarnished brand will be tougher. As a start, Mr Uchida promises 12 new models in the next 18 months to replenish its line-up. Each of the alliance partners will concentrate on what it does best; in Nissan’s case that is selling medium-sized vehicles, electric and sports cars in America, China and Japan.

Hardest of all will be repairing the alliance. The idea to share more parts to keep costs in check is sensible. But Nissan’s grievances over Renault’s 43% controlling interest in Nissan, compared with its 15% stake in Renault, have not gone away. The most notable thing about Nissan’s annual meeting on June 29th was strident denial that its executives conspired to oust Mr Ghosn, in part to forestall his plan for a full merger with the French firm.

Mr Uchida nevertheless hopes to achieve a 5% operating margin by 2023. That may seem “conservative” with respect to past ambitions, he concedes. But it would be a marked improvement from -0.4% last year.

Conservative or not, the goal looks a tall order. Details of the new parts-sharing arrangement remain sketchy. Consumers hit by the coronavirus recession may be reluctant to splurge on new wheels. And even if Mr Uchida succeeds in fixing Nissan he will struggle inside an alliance riven with internal tensions but too intertwined to unpick. He will not be probed on the future of the alliance, which he has been asked about “100 times” since taking the job. Further integration, he insists, is not something he and his opposite numbers at Renault and Mitsubishi talk about, and “we don’t intend to.” As for rebalancing the shareholder structure, he says, “It is not a discussion for us.” Such prevarication will only store up trouble. A smaller Nissan may not automatically translate into smaller problems.