Editor’s Note: This week, Peter discusses why “Design Matters” in Part II of his series. Andy Warhol’s automotive art makes an appearance at the Petersen Automotive Museum in Los Angeles in On The Table, and Elvis Costello is featured in our AE Song of the Week. The next chapter of Peter’s much-praised series on “The Muscle Boys” can be found in Fumes, which is his glorious take on big-bore V8s in American sports car racing. And in The Line we have coverage of F1 from Austria and Corvette Racing’s huge win at the WEC Monza 6 Hours. Enjoy! -WG

By Peter M. DeLorenzo

Detroit. I heard from a lot of friends in the business – especially in the Design community – who savored last week’s column and added their points of view as well. Though my perspectives ruffled quite a few feathers (Really? We’re shocked. – WG), my points were well taken and agreed with for the most part.

To further understand why design matters, you really have to think about how design affects our daily lives, because pretty much everything we come across in an average day is directly influenced by design. One thing about design that remains true is that even if most people don’t understand the inner workings of the process, or the whys and wherefores, they respond to what they like emotionally, as in, I want to go there. Or, I want to be a part of that, or quite simply, I want that.

Think about it for a moment. Our eyes are drawn to logo and typeface designs of all kinds. For instance, just walking through a supermarket aisle is a test of that, with graphics, logos and colors fighting for our attention at every turn. Or, how about digital shopping? Everything we see is visually presented and orchestrated to draw you in. Fashion in and of itself is a design kaleidoscope of fabrics, colors and styling crafted to entice people in for a closer look. Shoes, one of the most important dimensions of fashion, are constantly being reimagined to create design “looks” that are new, fresh and juiced with enough I just have to have that style that make them irresistible, at least to those so inclined.

What makes us gravitate to one shoe or another? Design. What about to a coat or a particular pair of boots? Design. And how about furniture? Design. Everything we come across as we go about our day is directly attributable to design, from residential and commercial architecture to graphic presentations in videos and on TV, and everything and anything in between. Even mundane places – such as gas stations and their attached convenience stores – have graphic designs helping to create their look and feel. Design sets the tone and creates an ambience, and even if we’re not consciously aware of its power and influence, it is always there.

And when it comes to automobiles, of course, it’s no secret that the power and influence of design are magnified exponentially. Design not only matters in the automobile business: It. Is. Everything.

Let’s consider one segment for this discussion: The one that is still (quaintly) referred to as “pony” cars. Started by the Ford Mustang in 1964 and followed by the Chevrolet Camaro, Pontiac Firebird, Plymouth Barracuda, Dodge Challenger and even the AMC AMX among others, this segment – now most often referred to as “muscle cars” – has endured through a series of peaks and valleys over the decades. Consumer interest in these cars is notoriously fickle, usually gravitating to the newest and latest cars when they hit the market, to the detriment of existing competitors.

Why pick what is basically a segment in limbo? Because it gives a good example of purity of design, and a segment that isn’t dependent on the vagaries of whatever the four-door crossover “coupe” of the month is. (Besides, four-door crossovers are so tedious. -WG)

There are only three cars to talk about in this segment: The Ford Mustang (not the Mach-E, please), the Chevrolet Camaro and the Dodge Challenger. The Mustang is expertly rendered with proportions that I consider to be damn near perfect. It harkens back to the original fastback Mustang just enough, and despite the modern pony cars’ inherent heftiness, it looks crisp, uncluttered and clean. This is design that works.

(Ford)

The Ford Mustang Mach 1.

The Camaro is another story. Full disclosure, my favorite Camaro of all time was the ’67-’68 Camaro. It was light, purposeful, it looked more compact – especially in Penske/Donohue-prepared Trans-Am guise – and it was the perfect counterpoint to the Mustang at the time. The Camaro has had several iterations over the decades – some more successful than others – but it’s no secret that I find the latest version to be a mishmash of themes and a disappointment. It’s fat in places – especially from the side – and it’s scrunched-up in others, as if to counter the ungainly profile, and it’s far from pleasing to the eye. GM designers have worked hard on this latest version, and it’s certainly better than what it was, but it lacks the kind of fundamental design cohesiveness that the nameplate deserves. I don’t know where GM takes the Camaro from here – if it even exists in the oncoming EV age – but this is a car that sorely needs to be reimagined, because right now it looks like a committee-think car with a very low desirability factor. And when it comes to a segment of cars that people don’t really need, that’s not even remotely good enough.

(Chevrolet)

This Camaro had a special color applied for the SEMA Show in 2018. The fact that we had to search and search through several sources to even find a decent Camaro shot says a lot about the Camaro’s standing within GM. And the fact that the company’s NASCAR entry is called a “Camaro” means nothing. The Camaro is officially lost in translation, apparently.

And finally, there’s the Dodge Challenger. Bigger and heavier than the other two machines in this discussion – to a notable degree, in fact – the Challenger nonetheless is the quintessential definition of a modern pony-muscle car. Talk about emotionally compelling design that matters: the Challenger is brutish, purposeful and badass, and it rings all the bells and pushes all of the buttons, especially in “widebody” form. The design conveys exactly what this machine is all about and does so in such a way that the desirability factor is simply off the charts. If you want to ride off into the sunset for the remainder of the ICE Age with your foot hard to the floor – and you don’t want to spend six-figure dough-re-mi to do it – the Challenger is the machine to get.

(Dodge)

Dodge Challenger R/T Scat Pack Shaker Widebody.

Yes, the aforementioned “pony” segment is a veritable blip on these manufacturers’ radar screens in this era of gussied-up and bloated “four-door” crossovers and SUVs. A sad and depressing era that has been reduced to a variety of front and rear clips – with sculptured side surfacing! – that supposedly counts for design “differentiation.” It doesn’t and it’s not.

But design still matters in this business, despite the tedious four-door crossover trend. You see it everywhere. How about the most profitable, highest-volume segment in the business? Don’t think that that design matters in pickup trucks? These car company design studios spend hours and hours and hours coming up with the right look for their pickup trucks. If they get it right, it can add multi-billions to the bottom line of the company. Conversely, if they get it wrong, it means a costly mid-cycle re-do. There are plenty of examples of car companies that came up short in the last decade because they didn’t go far enough – inside and out – with their trucks. We’re talking crushing disappointment, folks, and huge balance sheet disruptions, just because a company didn’t reach far enough or made misguided assumptions about what people would settle for, as oppose to what they really wanted.

Speaking of “design reach,” I am going to close this week’s column with some quintessential definitions of pure design reach. Are they practical? Not necessarily. Did they end up in production? Only parts of them. Then, why?

Because designers need to reach for the blue sky and dream of what could be. Because without it, the art of design will die in a cloak of mediocrity. And our world would be crushingly boring if that ever happened.

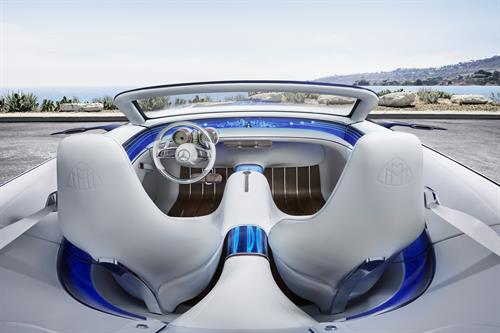

(Mercedes-Benz images)

The Vision Mercedes-Maybach 6 Cabriolet concept exemplifies the idea of “automotive haute couture,” according to Mercedes PR minions. And boy, does it ever. It is projected to be powered by a four-motor, all-electric, all-wheel-drive system with a combined output of 750HP, and capable of accelerating from 0-60 in under four seconds. Design reach, indeed.

(GM Design images)

(GM Design images)

No, the Cadillac Ciel concept never gets old. Now over a decade old, it still succinctly and perfectly captures the “idea” of Cadillac. A majestic car in person.

As I’ve reminded my readers frequently, in the face of a business that grows more rigid, regulated and non-risk-taking by the day, we must never forget the essence of the machine, and what makes it a living, breathing mechanical conduit of our hopes and dreams. And that in the course of designing, engineering and building these machines, everyone needs to aim higher and push harder – with a relentless, unwavering passion and love for the automobile that is so powerful and unyielding that it can’t be beaten down by committee-think or buried in bureaucratic mediocrity.

Design still matters? Yes, absolutely. In fact, with the onslaught of EV similarity, design is everything.

And that’s the High-Octane Truth for this week.