Like it or not, we live in a globalized economy. How you define or measure globalization can vary, but it tends to just mean greater financial integration among countries, as well as more political cooperation, immigration, and trade of goods and services. In all these domains, globalization has been on the rise until recently.

Some economists, pundits and politicians are arguing that globalization has peaked and will now start to reverse. Niall Ferguson sees this period of globalization, thanks to the pandemic, fading away with a whimper. Harvard economist Dani Rodrick is announcing the end of neoliberalism.

But globalization isn’t a phase; it’s a force that can’t be stopped.

There was a concerted push toward more global integration throughout the era following World War II. As the war ended, the global community created several large institutions (the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, the United Nations and the like) to facilitate more cooperation and trade and avoid the mistakes of the past. But globalization really took off after the fall of the Berlin Wall.

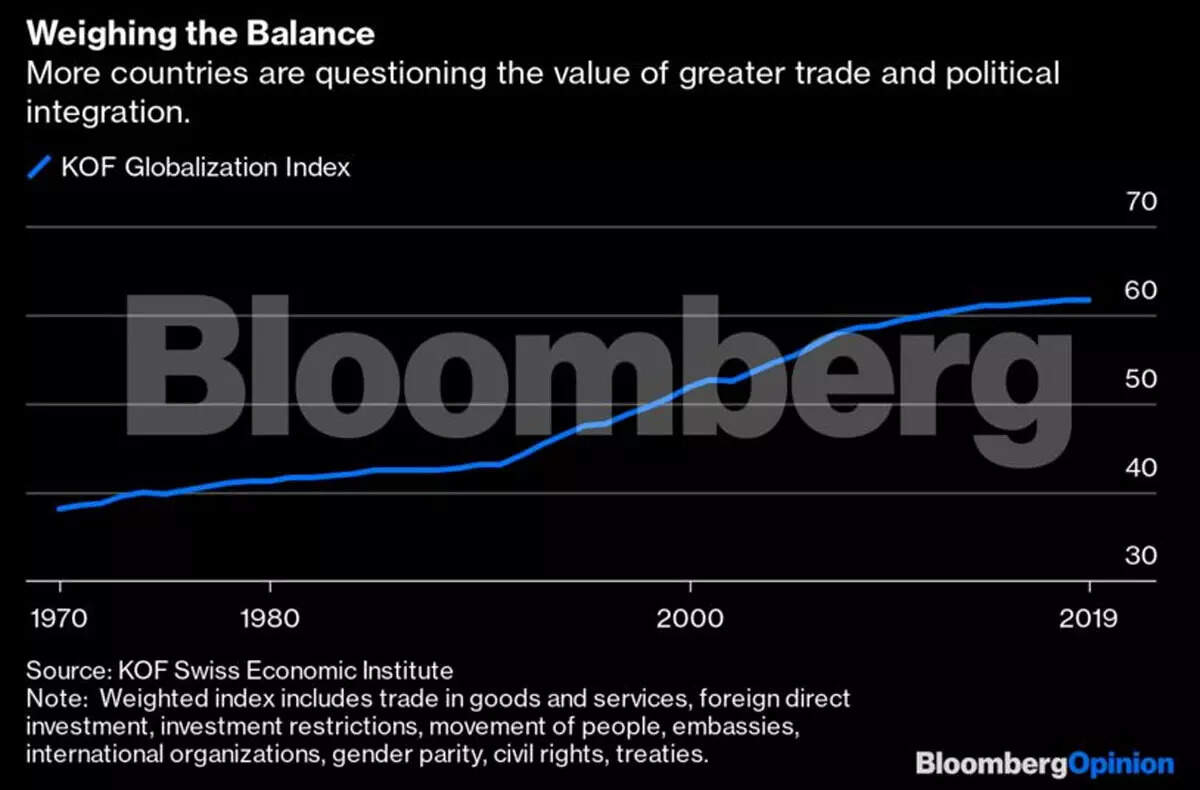

The end of the Cold War, improving technology that facilitated trade (especially of services and information) and an intellectual environment, such as the Washington Consensus, favored all things global. Countries dropped tariffs and more capital and goods moved across borders than ever before. You can see this in the KOF index of globalization, which includes various measures of economic and political integration.

But if you look closely at the index, there is a slowdown in the pace of globalization during the last decade. It peaked in 2008 if you measure it as trade as a percentage of GDP.

The last few years caused us to question the value of globalization. It delivered on many of its promises; more than a billion people no longer live in poverty. Goods and services are much cheaper, and diversification has made the economy less risky. But there were also problems. Bringing billions of lower-paid workers into the global market very quickly displaced many people in richer countries from their jobs and worsened inequality within countries. Dollarization meant some developing countries faced currency volatility as foreign investors pulled their money out at the first sign of trouble.

No surprise, then, that there has been a backlash against globalization accompanied by policies to slow or even reverse it. The pandemic, which led to shortages when trade slowed, only added to the disenchantment with globally integrated supply chains. Both political parties are pushing for industrial policies that subsidize more domestic manufacturing of certain goods. There are more tariffs on some goods and restrictions on capital. The IMF, once globalization’s biggest champion, now endorses capital controls.

The outlook appears even more dire. China’s once unstoppable economy — a big force in globalization’s rise — is not looking so good. The world may not be able to count on China for cheap and plentiful goods anymore. Meanwhile, a rising dollar and interest rates will put pressure on emerging markets, which will make them even more skeptical of global markets.

Nothing lasts forever. Human progress stumbles and can stall. But globalization is not going anywhere. First, it’s way too hard to unwind many of these relationships. We are all in bed together, assets and commodities are still priced in dollars and foreigners still own lot of US debt. Manufacturing depends on intermediate goods made all over the world that are not only cheaper, but made with skills we don’t have anymore. America’s recent attempt to re-shore semiconductor manufacturing illustrates why industrial policy is much harder than it looks and is not a good solution to structural job loss.

Second, the benefits from globalization are too good to walk away from. Many people no longer live in poverty and the world has become accustomed to cheaper stuff. We are seeing how disruptive and painful the return of inflation has been both economically and politically. Deglobalization would make inflation much worse, and no one wants that. It turns out politicians are quite flexible on their policy views (see phasing out fossil fuels) if it can deliver cheaper prices. Big talk on a retreat from globalization may be the next populist position to fall.

The economic and political trends that threaten globalization need not be so ominous. Ken Moelis, founder and chief executive officer of Moelis & Co., is concerned there will be a pullback on globalization because the war in Ukraine exposed how vulnerable we are to foreign countries. But that only shows how risky it is to depend on any one country, including your own.

Going forward, countries need more diversification when it comes to where they get their goods and commodities, not less. We may not be able to depend on China with its aging population and uncertain economic future, but more production may come from younger countries on the African continent, who still can benefit from more economic integration.

Globalization is far from perfect, but on balance it does make our lives better. New tariffs and industrial policies will take us a few steps back toward protectionism, but more trade can relieve pricing pressure and maintain the momentum toward more integration. The tone of discourse about globalization may have changed, but the genie is out of the bottle and won’t be contained.