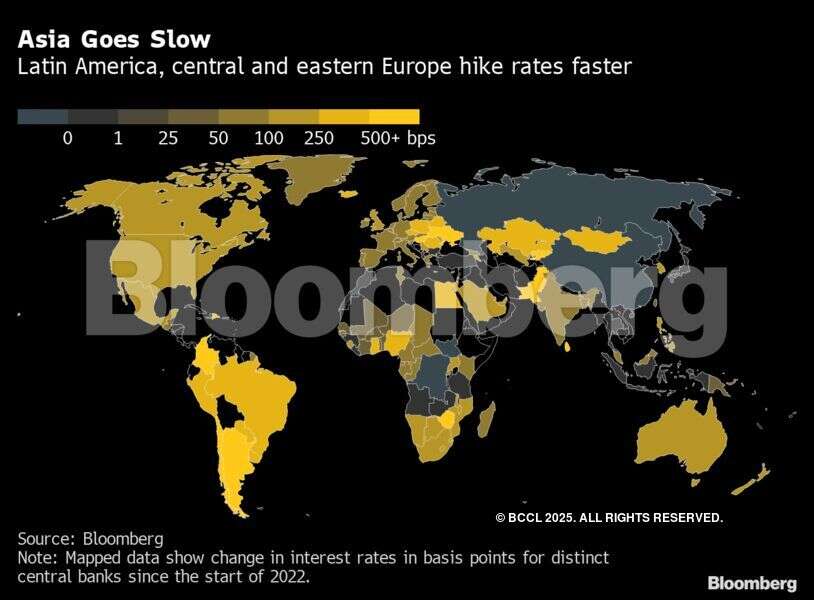

Asia’s emerging economies are drawing on large foreign exchange reserves to help prop up their currencies rather than going all-out with interest-rate hikes.

India, Thailand and Korea have seen their reserves drop by a combined $115 billion this year as they sold dollars to curb currency declines. While most central banks in Asia are also raising rates, economists see this aimed more at tamping down inflation than narrowing the rate differential with the Federal Reserve.

The hope in the region is that a relatively slow and shallow hiking cycle will be enough to keep a lid on price gains without sending economies into reverse.

“Emerging-markets Asia central banks are arguably less willing to indulge in competitive hikes,” said Vishnu Varathan, head of economics and strategy at Mizuho Bank Ltd. in Singapore. “The build-up of FX reserves provides some scope for these central banks to exploit this as a means to backstop currencies and contain imported inflation.”

China, the biggest emerging market of all and the top-ranked nation for currency reserves, remains on a different course to the rest of region. Its reserves have fallen by $179 billion this year to $3.07 trillion but the central bank has also lowered some key lending rates amid efforts to offset the impact of Beijing’s Covid-zero stance.

“Many Asian central banks have accumulated foreign reserves during periods of capital inflows and low US interest rates, which can now be drawn upon,” said Chua Hak Bin, an economist at Maybank Investment Banking Group. “Maintaining currency stability is important to shoring up economic confidence and lowering the threat to exporters and borrowers, especially for smaller, more open economies.”

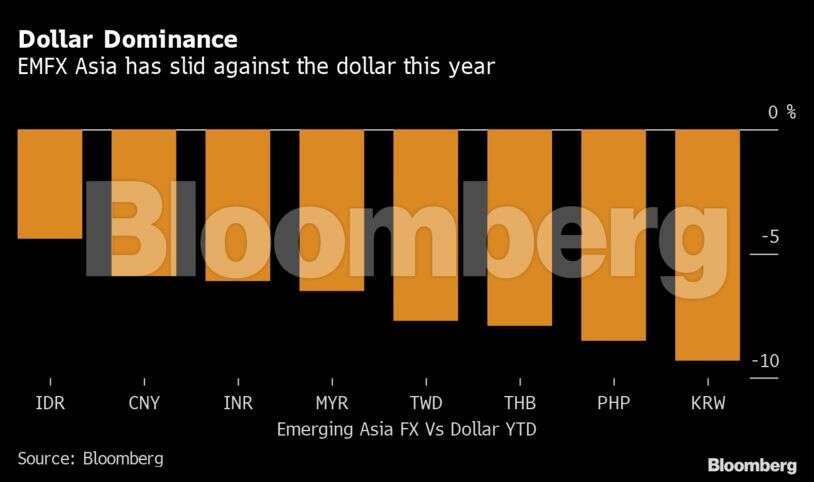

To be fair, almost no economy in the world has been spared the impact of the dollar’s relentless rise, but emerging Asia currencies have held up well on relative basis and despite a reticence to push hard on policy rates.

India has run down its reserves by $62 billion this year while raising its benchmark interest rate just 90 basis points. Even with an expected 50 basis points hike by the Reserve Bank of India on Friday, this will still be well short of the 225 basis points of increases by the Fed.

The rupee has dropped to a series of record lows during the period, but has managed to hold its place in the top half of the field for year-to-date performance among currencies in the region.

Lower rates and renewed appeal for equities and the tech sectors in India and South Korea should help rupee and the won, said Ashish Agrawal, head of FX and EM macro strategy research at Barclays Plc in Singapore.

South Korea, which began raising rates 12 months ago but let itself fall behind the Fed this year, has seen a near $25 billion of drop in reserves. The won is down over 9% since the beginning of January and has hit levels seen last seen in 2009.

Thailand has seen $28 billion of depletion in its reserves while maintaining rates at a record low and seeing the baht drop 8% to the lowest since 2006. The Philippines, Indonesia and Malaysia have also seen a drop in their reserves this year.

Mizuho’s Varathan cautioned that Thailand, the Philippines and to a lesser extent South Korea are showing a concerning degree of “cash burn” of dollars in their reserves when compared to times of previous crises for the region.

To be sure, reserves are not made up entirely of dollars and part of the reserve decline across countries reflects the drop in the value of other reserve currencies against the greenback, not just market intervention.

Policy makers have also looked beyond both reserves and rate hikes to support their currencies. The RBI has eased rules to attract more dollar inflows from non-residents and foreigners into its debt. South Korea has asked its National Pension Service for more active hedging when investing abroad.

“Rates hikes don’t always work in currency defense,” said Sonal Varma, chief economist India and Asia ex-Japan at Nomura Holdings Inc. “So central banks are using a mix of allowing some depreciation and expending FX reserves.”