Biden talks up electric vehicle revolution – but is America ready to give up gas?

President appears at Detroit auto show, where EVs are this year’s stars – but the road to electrification promises to be a bumpy one

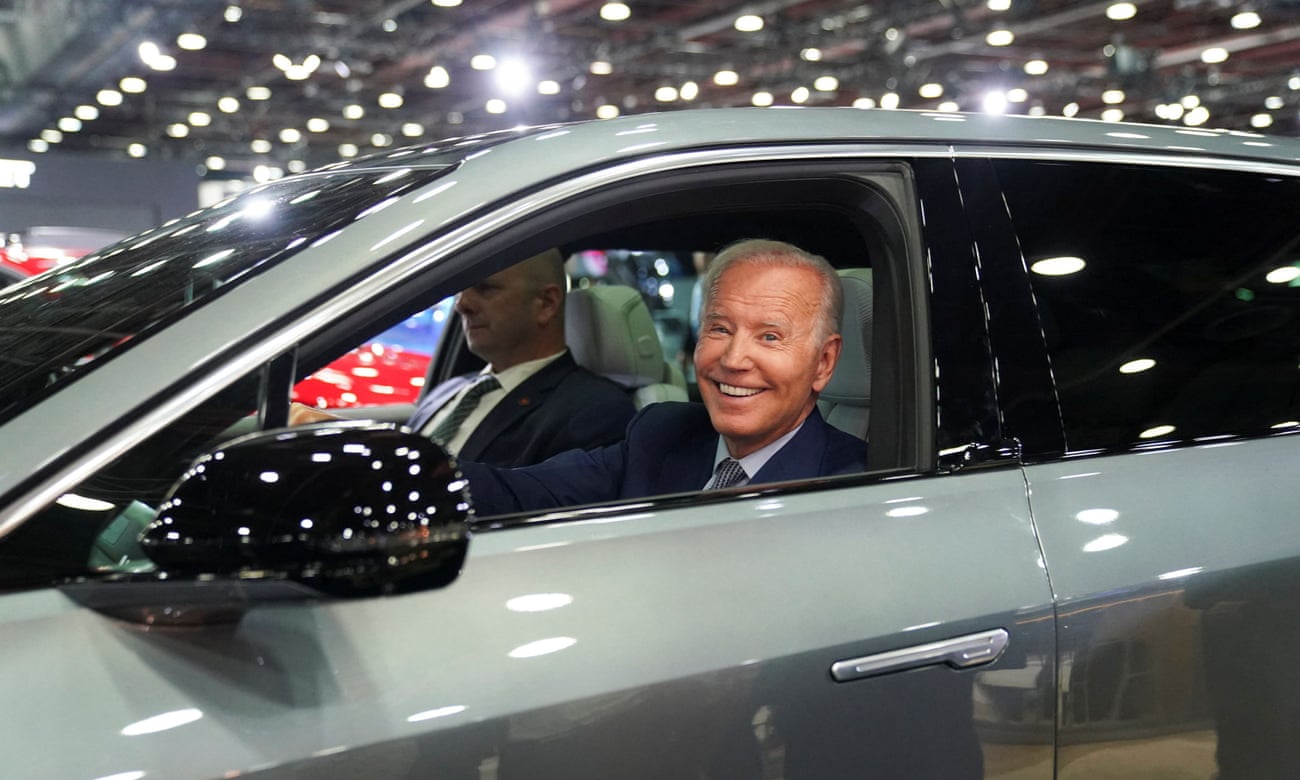

Fresh off signing legislation aimed at propelling the nation’s electric vehicle (EV) transition, Joe Biden was in Detroit last week to reaffirm his support for electrification ahead of the opening of the US’s largest annual car show.

“The great American road trip is going to be fully electrified, whether you’re driving along the coast, or on I-75 here in Michigan,” he declared as the first North American International Auto Show since 2019 prepared to open its doors.

Electric vehicles are the stars of this year’s show, which opens to the public on Saturday. But behind the glimmering showroom prototypes and lofty promises, real questions about the US’s electric vehicle ambitions remain.

At the press preview of the Detroit show, getting reads on the state of the US’s EV transition from analysts, officials, the president, and automakers is like administering a Rorschach test. Many praise automakers’ bold electrification goals, but others are skeptical after years of failed promises and low sales. Some hailed the federal government’s moves, while others say the president’s administration has not gone far enough.

Even Biden seemed to reveal mixed feelings as he test drove an electric Cadillac Lyriq SUV: “It’s a beautiful car, but I love the Corvette,” he said.

Like the president, most Detroit auto show attendees still prefer, and will next buy, a gas-powered car, even if the EVs are the event’s most hyped, said Michelle Krebs, executive analyst for Cox Automotive.

“It’s those flashy, glitzy vehicles that get the attention, and those just happen to be electric right now,” she said. “The EVs get more attention than the numbers that are sold.”

Opinions on the EV transition also partly depend on how one slices and dices the sales numbers. National market share for fully electric vehicles, called battery electric vehicles (BEVs), from January to August climbed to 4.8% compared with 2.3% for the same time period a year ago, industry analyst Edmunds reports. Monthly national BEV market share has remained above 5% since May.

That translates to about 436,000 sales in 2022 through August. Some view that as promising. Others see it as dismal.

Still, the auto show is about the future, and hyping still fledgling or non-existent EV lines this early in the game makes sense from a marketing standpoint. Automakers know electrification is the future and “they want to be part of the narrative and early adopters,” said Jessica Caldwell, executive director of insights at Edmunds.com.

“Nobody wants to be seen as being behind or as the dinosaur that will be out of business in 20 years,” she added. Still, even with the electric focus, no companies introduced a new EV, and Chevrolet, the company with the most EVs on the floor in Detroit, instead rolled out its massive new luxury gas-guzzling Tahoe SUV.

Even if the future isn’t yet here, significant money is being invested in developing it. In August, Biden signed an infrastructure bill that included $7.5bn for EV charging-station infrastructure. That same month he signed the Chips Act, which offers breaks for semiconductor manufacturers that produce key parts for EVs. And on Wednesday he announced a $900m investment in chargers, in the first round of funding for plans to roll out a network across the national highway systems in 35 states.

US automakers have invested billions in EV battery and assembly plants across North America, in part in response to the ascent of tech EV automakers, like Tesla and Rivian, and because some of its largest markets are legislating to ensure an electric future.

Tesla is now more valuable than all other US car companies combined, said Dan Becker, director of the Safe Climate Transport Campaign with the Center for Biological Diversity, and the legacy automakers are being pressured by shareholders to turn toward the future, he said. The lofty goals are partly an attempt to boost stock values.

“Wall Street investors are complaining to [GM chief] Mary Barra, and Ford’s investors are complaining to their brass, saying, ‘Hey, my neighbor has Tesla stock and made a fortune, and I have your stock and it’s in the tank,’” Becker said. “You need to do what they’re doing.”

He also pointed to a Chinese mandate that will require automakers selling in the nation of 1 billion potential customers to boost EV sales to make up 40% of all sales by 2030. In the US, California will phase out combustion engine sales by 2035, and other states are likely to follow suit. Such mandates are critical to the transition, Becker said.

“Auto companies make a lot of promises they don’t tend to keep unless there’s a law to back them up,” he added.

But even with all these pressures, the EV market still faces roadblocks. Not least that the average US car is 12.5 years old. “If a Californian buys a 2035 gas-guzzler, that will probably be on the road 20 years later, guzzling and polluting,” Becker added.

Which companies are serious?

In October 2021, GM hit the headlines when it was reported it would sell “only zero-emission vehicles by 2035”.

But the promise comes with a caveat. Barra said the company “aspires” to electrify its light-duty vehicle fleet by 2035. It said nothing about its large, luxury gas-guzzlers, which are popular and pull in huge profits for the company.

“An ambition does not necessarily equal vehicles, and Mary Barra didn’t make the promise – she said there was an ambition,” Becker said.

On a shorter timeline, the company is aiming to have 1m EVs on the road and electrify 40% of its fleet by 2025. Its Ultium platform – consisting of batteries, motors, software and other components – is allowing GM to push down costs while improving battery range, Caldwell said.

On the floor at the auto show, GM’s Chevrolet was the only brand to showcase vehicles that could be marketed to a wide range of consumers, including an electrified Blazer, Equinox, Silverado and Bolt. Meanwhile, GMC and Cadillac have rolled out higher-end, large SUVs in the Hummer and Lyriq.

But the achievability of GM’s goals are in question. The company has sold fewer than 18,000 BEVs through August 2022, and many of those were the Chevrolet Bolt, a car that Krebs characterized as a “disaster”.

“GM is not much ahead of the game, but they’re ambitious,” she added.

Ford, with 26,000 BEVs sold this year through August, is second worldwide in sales to Tesla. It recently doubled its annual production plans for its hit F-150 Lightning and is now attempting to assemble 150,000 annually, and deliver 200,000 by the end of 2023. The Mach-E, Ford’s electrified Mustang, is generating similar demand, while the E-Transit owns about 95% of the electric van market through July.

“Ford seems to be having products that really hit the mark,” Caldwell said.

Stellantis, formed from the merger of Fiat Chrysler and Peugeot, meanwhile, is viewed as playing catch-up.

And, unlike its American counterparts, Toyota didn’t have any BEVs on the floor in Detroit, though it did showcase a plug-in Prius Hybrid. Hybrids comprise about 25% of its sales, and analysts say the company has remained focused on them because it doesn’t believe there’s a strong market for BEVs.

“Toyota and Honda are asking the same question – is the consumer really there yet?” Krebs said.

Are customers ready?

Analysts say price is the No 1 obstacle facing the EV transition. The average EV sale price hit nearly $62,000 in August, up from about $57,500 a year prior. That compares with an average of $47,200 for all vehicles. The average US income is about $65,000, Krebs noted. “That math doesn’t work,” she said.

Cheaper EVs are here, and more are coming. Tesla now sells a $47,000 model, the Bolt is about $32,000, and more models under $40,000 will hit the market in 2023. Tax credits of up to $7,500 made available under the Biden infrastructure bill could help, but stringent requirements will limit their use, and they can be used on hybrids, which still use gas.

And then there are supply problems. Despite costs and other issues, demand for Ford’s Lightning is still outpacing supply, which is a blessing and curse for Ford: a consumer who orders one at the auto show may not get it until some time in 2024, and that’s costing the company customers.

“Consumers don’t want to hear that,” Caldwell said. “Americans are used to wanting to buy a car, going out today and driving it home tonight.” The delay is partly attributable to supply-chain squeezes, though those growing pains will probably work themselves out in coming years.

The US’s inadequate EV charging station network and still shaky technology is also driving away some customers, Caldwell said, adding that installing a home charging station makes the car-buying process even more daunting.

“Companies and their dealers need to say, ‘We’re going to make this as seamless as possible, we’re going to show you how to install a charger at home, we’re going to help you get the tax rebate, we’re to walk you through this from A to Z,” she said.

Regardless, the return of the Detroit show is giving consumers a solid taste of what the near future will look like, even if the road there isn’t as smooth as some would hope.

“I tell everybody: this is not going to be a linear transition – it will be a bumpy, windy road,” Krebs said.