The world over, the auto industry is rapidly heading towards an electric-only future, and just a few years ago, India too considered a 100 percent EV target by 2030. However, it has since rationalised that to a more realistic 2040. Interestingly, despite the EV target, ethanol flex-fuel vehicles are being seriously evaluated, and the Indian minister for road transport and highway is also actively campaigning for the cause too. Is there a case for biofuel and what’s behind the rising confidence in it?

Ethanol-blended fuel is not new to India – for over a decade now petrol here is mixed with ethanol, albeit a small amount of about 2 to 3 percent. Since low levels of ethanol – roughly around 10 percent – have no detrimental effects on current internal combustion engines, ethanol doping was done to lower India’s crude oil import bill. Over the past few years, this doping level has increased to about 10 percent, which the government plans to take up to 20 percent by 2025.

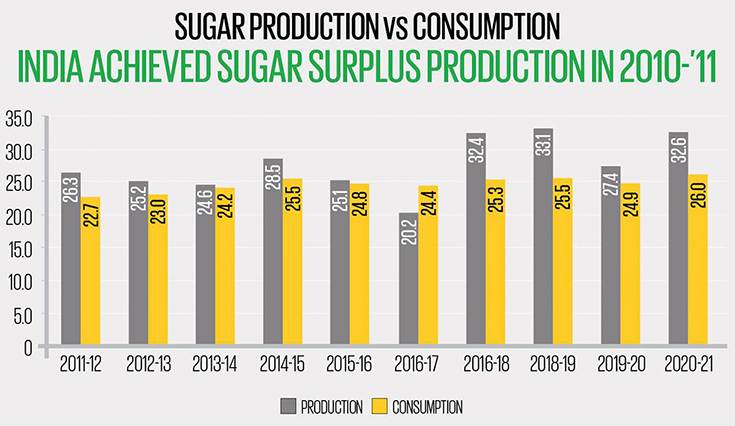

Enabling this is sugarcane, ethanol’s primary source and a crop India has long been producing. In 2010-’11, India achieved surplus sugar production, comfortably exceeding its domestic consumption and has done so ever since. Thus, for a while now, the country has diverted some amount of sugar cane towards the production of ethanol for use in petrol blending. However, going forward, increasing fuel consumption along with an increasing blend percentage will mean more ethanol will be required, but this is something all stakeholders say is easy to achieve.

Sugarcane could deliver a sweet deal in lowering automotive emissions.

Sugarcane could deliver a sweet deal in lowering automotive emissions.

Going by petrol consumption estimates and factoring in a blend of 20 percent ethanol, India will require 1,016 crore litres of ethanol in 2025, which is significantly lower than India’s projected supply of 1,500 crore litres of this biofuel. The public sector oil marketing companies that are under the administrative control of the Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas are also setting up twelve 2G bio-refineries with an investment of Rs 14,000 crore. Besides bagasse, which is sugarcane residue left behind after extraction of juice, 2G or second-generation ethanol is produced from agricultural residues like rice and wheat straw, corn cobs and even empty fruit branches. Thus, these 2G ethanol plants will increase ethanol production, and importantly, will do so from agricultural waste.

The additional benefits here are obvious, 2G ethanol is a good example of waste-to-wealth creation for the farming community. It can also potentially divert a lot of crop waste that would have otherwise been burned and added to air pollution. The use of ethanol will also aid India’s Conference of the Parties (COP26) commitments to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), where it has stated that 50 per cent of its energy requirements will be met from renewable energy by 2030.

Shift to ethanol: Reducing emissions via ICE vehicles

So, while ethanol production has good potential in India, the question arises – in an EV future, will there be demand for internal combustion engines (ICE)? And the answer to that is yes. Given the uncharted territory that the automobile industry is headed towards, there is no definitive answer as to when EVs will be the only source of personal mobility, and timeframes vary from study to study. One fact that all agree on, however, is that ICE vehicles will still form the majority, for the next decade at least.

Besides cane waste, second-generation ethanol can be produced from crop residue after a harvest and even empty fruit branches. Thus, it can reduce stubble burning and lower pollution too.

Besides cane waste, second-generation ethanol can be produced from crop residue after a harvest and even empty fruit branches. Thus, it can reduce stubble burning and lower pollution too.

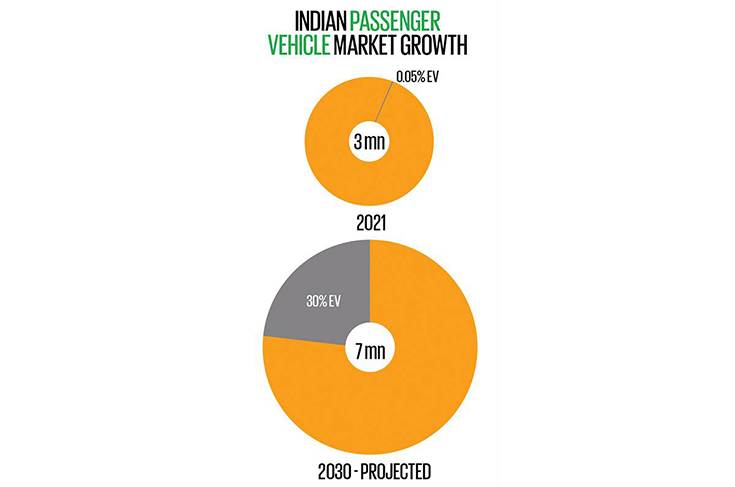

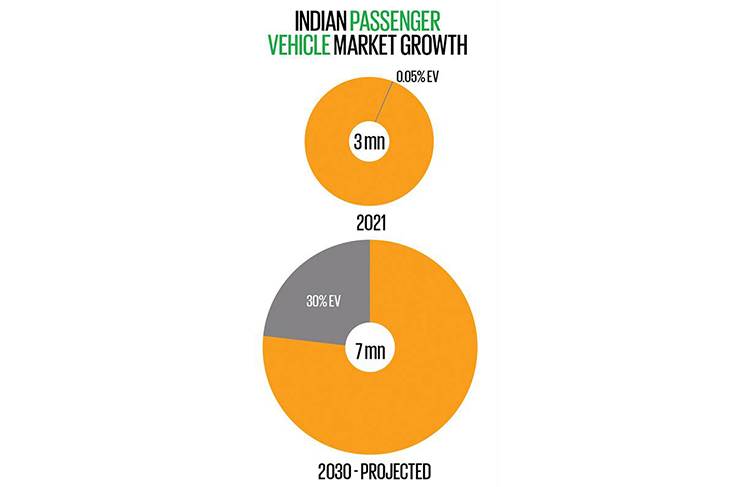

The Indian passenger car market is expected to grow from 3 million units last year to a 7-million-unit market in 2030. Of this, while estimates vary widely, nearly all agree that EVs will not exceed 30 percent, which means even at that level, a massive 5 million odd units will still be driven by internal combustion engines. And ICE vehicles will also continue to be a part of our landscape for a while. Speaking at the 62nd SIAM Annual Convention in New Delhi, Arun Goel, Secretary, Ministry of Heavy Industries, said, “ICE vehicles in India will co-exist with various electrified and greener fuel technologies powering cars at least for the next 20 years.”

It’s clear that something needs to be done to reduce these emissions too, which is where the government’s E20 plan plays a part. With a 20 percent ethanol blend not only will the country be reducing its crude imports, it will also mean a cleaner fuel is being burned, as ethanol, being plant based, has the lowest carbon emissions on a well-to-wheel basis.

Shift to ethanol: support from the industry

To run E20 fuel, however, requires modifications to the engine – mainly material changes to bits like hoses and fuel lines as they need to handle the extra corrosive nature of ethanol. Engine tuning also needs to be tweaked to handle ethanol’s lower energy density and, of course, to enable the engine to meet emission regulations.

However, unlike past regulations, for instance – leapfrogging from BS4 to BS6 stage emission norms in 2020 – the auto industry is not as apprehensive with E20 as the technology remains the same (internal combustion) and only simpler modifications are required to adapt to the new fuel. As Vikram Gulati, country head and senior VP (Corporate Affairs & Governance) at Toyota Kirloskar Motor, said to Autocar India, “It [ethanol fuel] has been there for decades, so it does not require research and it’s not that much of a challenge, but yes, people would require some lead time from a point of view of development and implementation only.”

Toyota is quite clearly behind ethanol-fuelled vehicles and has brought to India a flex-fuel Corolla hybrid to serve as apilot project – to showcase the technology and create awareness about ethanol. While India will target a 20 percent ethanol blend, the Corolla is a flex-fuel vehicle meaning that it can run any blend percent, even pure ethanol only. This is what Toyota also wants to highlight; even beyond E20, the industry can go to full flex-fuel vehicles. Gulati adds, “You only need sensors in the tank to determine the fuel mix, so it’s a little bit of development, but nothing any OEM today cannot manage.”

On flex fuel, Minister for Road Transport and Highways Nitin Gadkari is also optimistic. Speaking at the unveiling of the flex-fuel Corolla, he said, “With flex engines running only on ethanol, we will only need 4,000 crore litres” – production of which, most say, India can potentially achieve in this decade.

Shift to ethanol: tackling challenges

The ethanol path is not all rosy though, while new cars will be E20 compliant, older cars will have issues with the higher corrosive nature of the fuel. While there is a study underway at ARAI measuring the impact of E20 and higher ethanol blends, there is certainly going to be an issue with older cars running E20. Thus, one possible workaround is to continue the supply of E10 blends. Distribution and storage would pose a challenge, but not so much for refineries as the blending of ethanol and petrol is quite simply a mixing that happens after distillation, and downstream in the overall production process.

Going fully into flex-fuel vehicles also has challenges: for one, they should ideally be coupled to a strong hybrid system, as in the case of the Corolla. Ethanol has a lower energy density, and thus, running higher blends of it reduces an engine’s fuel efficiency, which can drop by as much as 30 percent. This is precisely where the strong hybrid system comes in, as it more than offsets this loss

However, this dependence on strong hybrids to back-up full flex-fuel vehicles can turn out to be their Achilles’ heel in India. The Indian auto industry is clearly divided on strong hybrids, with manufacturers like Tata Motors and Mahindra – who do not have such tech – saying it’s best skipped altogether, while brands like Toyota and Maruti are clearly behind it. So while E20 compliance will be industry wide, given the mandate, it remains to be seen what the prospects for full flex-fuel vehicles will be here in India.

However, this dependence on strong hybrids to back-up full flex-fuel vehicles can turn out to be their Achilles’ heel in India. The Indian auto industry is clearly divided on strong hybrids, with manufacturers like Tata Motors and Mahindra – who do not have such tech – saying it’s best skipped altogether, while brands like Toyota and Maruti are clearly behind it. So while E20 compliance will be industry wide, given the mandate, it remains to be seen what the prospects for full flex-fuel vehicles will be here in India.

Full flex-fuel vehicles will also further drive up demand for ethanol, and if not met fully by 2G ethanol, it would mean food crop and agricultural land for food production gets diverted to producing fuel, which drives up food costs. And in the past, this has been witnessed in nations like the USA, which have a large ethanol fuel industry. The USA had mandated increasingly higher blends of ethanol, which had driven up the prices of corn, the main source of ethanol in the US. Thus, as India heads towards ethanol fuel, careful assessment needs to be undertaken to avoid unintended consequences, especially with regard to food security.

In any case, ethanol will play a larger role in our automotive landscape and be a key cog in what is shaping up to be a multi-energy market. As Gadkari mused aloud, “The Indian automobile market is an ocean, and bring it all – flex-fuel, petrol, electric, CNG, green-hydrogen – all will have a place here.” Indeed, as we and many others have said before, the solution to clean mobility does not lie with a singular tool, but will come about from a carefully thought-out and targeted multi-fuel approach.

In any case, ethanol will play a larger role in our automotive landscape and be a key cog in what is shaping up to be a multi-energy market. As Gadkari mused aloud, “The Indian automobile market is an ocean, and bring it all – flex-fuel, petrol, electric, CNG, green-hydrogen – all will have a place here.” Indeed, as we and many others have said before, the solution to clean mobility does not lie with a singular tool, but will come about from a carefully thought-out and targeted multi-fuel approach.

Copyright (c) Autocar India. All rights reserved.