The year 2022 has not been a pleasant one for Thomas Mastrobuoni. The chief investment officer of Big Idea Ventures, a foodtech investment firm backed by Singapore state investor Temasek Holdings, recently found himself for the very first time in a position of having to turn down a pitch without even giving it a look.

“Dude, save the stamp,” Mastrobuoni had told the potential investee. “Don’t send me the deck because I’m not going to do anything with it, and I don’t want to increase your expectation.”

As with most other sectors, valuations of foodtech companies have fallen from the peaks witnessed in the pre-COVID era, when billions of dollars were chasing the nascent players setting out to disrupt the $6.3-trillion food industry. But some entrepreneurs, still excited by the fundraising frenzy of the past, are having a hard time adjusting to this new norm.

“We are starting to see opportunists,” said Mastrobuoni, who reviews over 1,100 pitches a year. Entrepreneurs need to have “realistic valuation expectations”.

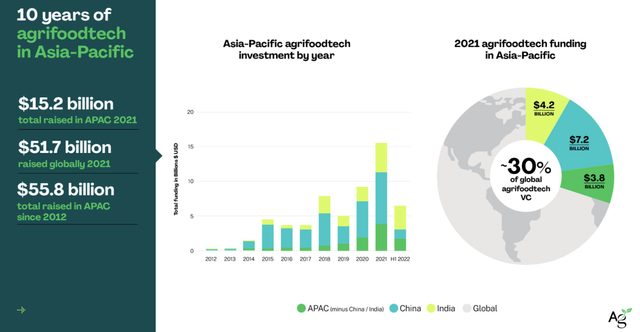

Mastrobuoni is not alone in feeling the chill. Venture capital (VC) investment in the global foodtech space fell to $2.7 billion in the third quarter of 2022, down 76.9% year-over-year (YoY), according to PitchBook data. It marks another quarterly retreat from the $5.6 billion recorded in Q2. It had already fallen 21.5% sequentially from Q1.

The bad news is: things may go from bad to worse in 2023. While Europe and the US will likely face a recession this year, the Asia-Pacific region is expected to lead global economic growth, but not without weathering through headwinds such as interest rate hikes, geopolitical tensions, and a projected slowdown in China.

“You [the startups] need to price yourself appropriately,” said Rob Leclerc, founding partner of San Francisco-based AgFunder. “They [the investors] are not interested in flat or down rounds. You could exclude yourself pretty quickly from the market because you’ve set an expectation regarding the maturity of your company that you have not met.”

In the Asia-Pacific, venture investors behind some of the region’s most promising foodtech startups have seen more “adjusted rounds” and “more talks about adjusted rounds” in segments ranging from plant-based meat, cellular agriculture, and precision fermentation to agricultural technology, and novel ingredients development.

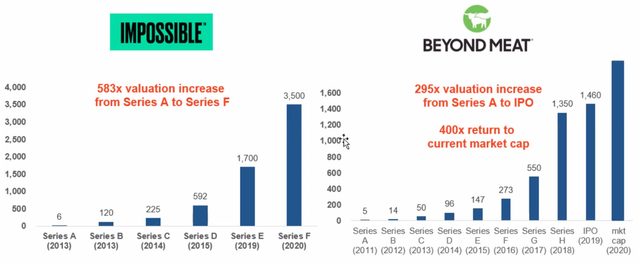

The struggle of Nasdaq-listed Beyond Meat, whose stock has slumped more than 80% in the past year, makes some wonder if the number of consumers of meat substitutes has reached its limit.

Other publicly listed folks including Else Nutrition Holdings Inc also did not fare well in the market downturn. The Canada-listed Israeli company, which provides plant-based baby and toddler nutrition, saw its stock price halve last year amid revenue declines and production delays.

A gloomy sentiment is especially seen among generalist investors, who contribute to the bulk of capital flowing into foodtech startups. “Some investors who don’t know this category are becoming more risk-averse. They are pulling back a bit or just hitting the pause button,” said Nick Cooney, founder and managing partner of alternative protein-focused VC firm Lever VC.

This will lead to longer due diligences and funding cycles.

Singapore shows the way

Despite a growing air of panic, specialist investors and emerging players remain hopeful about the industry’s future. They point to the fast-rising awareness around foodtech as an important solution to food security, and sustainable development.

Asia-Pacific is catching up with more developed markets including the US and Europe, with more investors showing an interest in alternative proteins — a key foodtech segment. Alternative protein startups in Asia-Pacific raised a combined $312 million in 2021, almost doubling from the previous year, according to a report by the non-profit industry think tank Good Food Institute APAC.

In Asia, Singapore arguably had the most profound realisation regarding the urgency to boost foodtech investments after the loss of one-third of its chicken supply following Malaysia’s export ban in early-2022.

The city-state is doubling down on foodtech by attracting industry talent, building facilities, removing regulatory hurdles, and providing government subsidies as well as startup financing. State investor Temasek is growing into one of the most active and deep-pocketed investors in Asia’s foodtech space.

“Singapore has already taken the lead in Asia,” said Mattan Lurie, a portfolio manager at VenturesLab, where he takes care of synthetic biology and other foodtech-related portfolio companies. “Governments never move quickly, even on things that are important to them. [However] Singapore is very progressive because it [food security] is a national security issue.”

“The role of Singapore has become extremely important in the global evolution of foods,” opined Lurie.

Among its efforts to promote foodtech, Singapore became the first country to allow the sale of lab-grown meat by giving a go-ahead to American startup Eat Just’s cell-cultured chicken in late 2020.

It actively supports both indigenous and global foodtech companies, as well as investment firms through government-backed institutions such as Enterprise Singapore and the Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*STAR). The city-state is charging through its “30 by 30” goal of locally producing 30% of domestic nutritional needs by 2030.

Next Gen Foods, the creator of plant-based chicken alternative TiNDLE, positions Singapore as its global headquarters even though the US, the UK, and Germany currently account for over 90% of its business.

“Setting up a headquarters for us was not a decision based on short-term market needs, but instead, long-term ambition,” said Andre Menezes, Next Gen’s co-founder and CEO. “While the US and Europe are incredibly relevant parts of our business in the short term, we do see that our foothold in Singapore — for the objective of being able to develop broader in Asia as we progress — is key.”

Founded in April 2020, Next Gen raised $100 million in February to step up its global expansion. Investors in the latest round include GGV Capital, Southeast Asian VC Alpha JWC, UK-based MPL Ventures, as well as Singapore’s EDBI and Temasek, which invested through its recently established Asia Sustainable Food Platform.

As he saw “signs of accelerated adoption and acceptance” of alternative proteins in Asia, Menezes pointed to China and India as the two markets with “tremendous potential” due to the sheer size of their populations.

For Next Gen’s plant-based chicken products, countries like Japan and South Korea are promising as well, given their citizens’ favour for chicken cuisines and the concentration of high-purchasing-power consumers in urban cities. The two markets are both “in a sweet spot” of being big enough for businesses to scale, said Menezes, who also put emerging markets like the Philippines under his radar.

A shift in the playing field

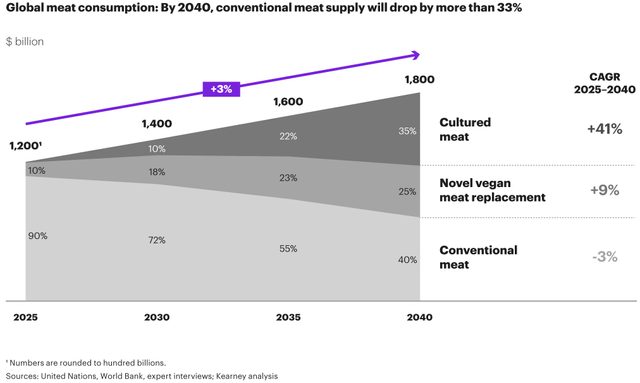

With Asia rising as the world’s next growth engine, the demand for meat and premium protein is expected to grow among its increasingly affluent population. China alone consumed nearly 30% of the world’s meat in 2021, according to a recent report in Earth Journalism.

Environment-conscious investors certainly do not pin their hopes on animal husbandry to feed the region’s 4.7 billion population.

Data from the Humane Society International, an animal welfare group, show that animal husbandry is responsible for at least 16.5% of global greenhouse gas emissions and significant environmental degradation from biodiversity loss to deforestation.

In a more capital-restricted environment, fundamental foodtech developers are gaining more traction, while the overcrowded consumer packaged good (CPG) space is becoming less desirable to investors.

There is “a race for eyeballs” among CPG companies, which have flooded the market with “too many brands yet very little product differentiation,” said Big Idea Ventures’ Mastrobuoni. He foresees a severe manufacturing challenge ahead for CPG players.

More investors like himself are shifting sights to what he calls the “backbone” of foodtech — whether it is novel ingredients or bio-reactor technology or intelligent software to enable precision fermentation.

This is precisely the case with Mastrobuoni’s investments in startups like Singapore-based Pullulo, which develops microbial proteins for applications in alternative protein products, as well as the underserved healthcare foods market.

“Many entrepreneurs are flowing into the plant-based food space, but not many of them are making profits due to their high reliance on raw materials,” said Pullulo’s founder Jonathan Cheng.

He is poised to help address the supply problem through Pullulo’s fermentation technology, which focuses on the upcycling of agriculture leftover fruits and vegetables, with the conversion of carbon dioxide to produce microbial proteins and nutritious byproducts such as lactic acid and probiotics.

The startup now sources fruit and vegetable leftovers from a few million farmers in the Philippines, while building out similar operations in Indonesia and Vietnam.

Emerging entrepreneurs view their proximity to Asian consumers and the local food culture as a key factor for them to win in the foodtech market.

Jen-Yu Huang, the co-founder of San Francisco-based foodtech startup Lypid, set up an office in Taiwan earlier this year to provide the market with the firm’s self-developed vegan fat.

Lypid, which closed a $4-million seed round led by Green Generation Fund in March, is also planning to build a pilot production line in Taiwan.

The startup already partners with Louisa Coffee, the island’s largest coffee chain, to deliver plant-based burgers made with Lypid’s animal-like vegan fat PhytoFat. Across Asia, the startup is expanding in countries like Japan, South Korea, and Thailand with existing clients including the Thai poultry and pork giant CP Foods.

It is crucial to “make our technology closer to consumers” because Asian cuisines require a different R&D approach compared with the Western ones, said Huang, who then exemplified Asians’ preference for braised food and the prevalence of vegetarian culture in the region.

Huang said that Lypid plans to raise a new investment of up to $12 million by late 2023, as the startup continues to invest in partnership expansion and the construction of its facilities in Asia and the US.

New fund launches

As entrepreneurs forge ahead with their expansion plans, one major challenge in navigating the market turmoil is how to boost the adoption of foodtech products.

In the case of alternative proteins, the key question is: Will those eco-friendly innovative foods be comparable with, if not better than, traditional animal meats in taste, texture, price, and accessibility? Venture investors behind nascent foodtech startups believe that we are not too far from that target.

Albert Tseng, co-founder of Dao Foods International, and his team are deliberating over the idea of raising a new fund as the firm is on track to building a portfolio of 30 foodtech companies by the end of 2023.

Although short-term headwinds have pushed many consumers to “retreat to familiarity,” Tseng said that he is “cautiously optimistic” about the industry growth in the coming year. “Young consumers still have the curiosity for novel products and foods. I think that [consumption of alternative protein] will return.”

China-focused Dao Foods International has deployed 70% of its 2020 Vintage Fund I with investment in nearly 20 startups, about 75% of which currently have operations in mainland China.

The firm’s portfolio companies include Starfield Food Science & Technology, a Chinese startup currently delivering plant-based meat alternatives through partnerships with over 40,000 stores across the nation. Its products are available across retail warehouse clubs, convenience stores, as well as coffee and tea shops under brands such as Sam’s Club, Luckin Coffee, FamilyMart, Dicos, and HeyTea.

As an ascending foodtech star, Starfield is a sought-after investment target for many in the venture circle. The Shenzhen-based startup raised $100 million in a Series B round led by Primavera Capital Group in January, with participation from existing investors like Sky9 Capital, Joy Capital, Matrix Partners China, and Lightspeed China Partners. Alibaba Group’s strategy chief Ming Zeng also participated in the deal.

While Starfield did not disclose its valuation, it could well be one of China’s first foodtech startups to hit the $1-billion unicorn mark.

“Because China’s population is four times the size of the US and food culture is an important part in the country, I don’t see any reason why there couldn’t be multiple companies that have the success at the level of Beyond [Meat] and Impossible [Foods] in China in the next 3-5 years,” said Tseng.

This confidence in the long-term prospect of Asia’s foodtech is widely seen among venture investors. Their fundraising momentum is proof of this optimism: Alterative protein-focused Lever VC started raising capital for a new $250-million Fund II a few months ago, with a target to close the fund by end-2023.

AgFunder, which runs the GROW Asia Fund in Singapore to support Asia’s foodtech startups, reached the first close of its Fund IV at $60 million in March. It targets a total fund size of $100 million. The firm’s Asian franchise AgFunder Asia also teamed up with SDG Impact Japan in the same month to launch a joint vehicle targeting up to $50 million for investments in early-stage agrifood tech companies in Japan and Southeast Asia.

Smaller-sized specialist investors also made good progress. Better Bite Ventures launched a $15-million fund in February to invest in the pre-seed and seed stages. In Singapore, Good Startup is planning to raise its second fund in the coming few months at a size larger than the 2022-vintage, $34.1-million debut fund.

Among generalist investors, Singapore’s Temasek was ranked as one of the world’s top three investors in agriculture, food, and land use in 2021, with over $8 billion of capital invested in food-related companies since 2013. The region’s impact fund managers, such as MDI Ventures and Heritas Capital, have also included foodtech as one of their focused areas for newly-launched vehicles.

New participants raise exit hopes

Interest is increasing among not only investment companies but also traditional family businesses and food conglomerates.

While early-stage investors believe these new participants will bring more exit opportunities, many of them pointed out that, in the foodtech space, investors should think ahead about their exit strategies and structure valuations within a certain range to ensure appetite.

For Manav Gupta, founder and CEO of Brinc, the “sweet spot” is in the $100-250 million valuation range. “Our target is not chasing the unicorns… It’s about building a strong business with strong fundamentals. Building that up over the years and then, if the goal is to exit, selling to a corporate that has more infrastructures to help it scale,” said Gupta.

Gupta and his team at Brinc, a Hong Kong-headquartered venture accelerator, are planning to raise two venture funds in 2023, including one dedicated to foodtech investments in Asia. With about 50 out of its over 200 portfolio companies in the food space, the firm is confidently targeting a size of $50-$100 million for its first Asia foodtech fund.

Brinc supports foodtech companies including India’s first lab-grown meat startup Clear Meat, mainland China’s first cultivated meat firm CellX, as well as Avant Meats, the first cellular technology startup in Hong Kong.

“That [the valuation range of $100-250 million] is the ideal spot, at which point a corporate may get interested in acquiring,” said Gupta.

A successful sale could just bring the kind of return multiples enough to crack a smile on investors like AgFunder’s Rob Leclerc.

Leclerc and his team at AgFunder saw New York-listed Deere & Co, the world’s largest farm equipment maker, acquire its portfolio company Bear Flag Robotics, an agriculture technology startup in Silicon Valley, for $250 million in August. The acquisition came only a couple of years after AgFunder had first invested in Bear Flag’s seed round in the summer of 2020. Back then, the startup was valued at $25 million post-money.

It was “a tough journey” for Bear Flag raising its seed round during the pandemic, Leclerc recalled at a webinar in November. In just a few more months, its valuation moved up to about $1 billion on the day of the acquisition, he revealed.

“You sort of model out acquisitions by corporates in the range of $200-500 million. Once you go beyond $500 million, corporates like John Deere probably won’t have that appetite unless your business has serious profits,” said Leclerc. “If you look at Impossible Foods, they have a valuation — too high to be acquired.”

Other investors could not agree more. In fact, the rising participation of large-scale food companies is becoming “a contributor” to the industry’s growth, said Michael ByungSun Hwang, CEO of Bigbang Angels.

Bigbang Angels, a South Korea- and Singapore-based early-stage VC with a focus on cross-border startups, has its own foodtech investments including smart farm solutions provider Firmmit. According to Hwang, Firmmit managed to keep doubling its annual revenues for the past three consecutive years, as it is estimated to book up to $10 million in revenue this year.

Large corporates in South Korea, such as food-to-entertainment conglomerate CJ Group, as well as food and beverage company Nongshim, have started looking into early-stage startups, said Hwang. He said that traditional food businesses are growing an appreciation of smart technologies as a way to help them enhance the stability of farming activities and increase profit margins.

Although foodtech in Asia is still in a nascent stage, the good news is that one may not have to wait for a long time to harvest returns from early-stage bets.

“We’re seeing more investors keep an open mind towards early-stage participation,” said Victor Chen, founder and CEO of Foodland Ventures, an Asia-focused foodtech VC and accelerator. “Players in the industry see the need to invest in future and innovative solutions to help them do businesses… It’s becoming something that directly impacts their businesses, and they see more of a need to make a change.”

Foodland Ventures, which has offices in Taiwan, Singapore, and North America, is raising its Fund II to finance its search for talented foodtech entrepreneurs and partners in Taiwan and the entire Asian region, excluding China. It is expected to close the new fund around Q1 2023.

But don’t be dazzled by the great upside potential. It is not yet time to sit around the campfire, holding hands and eating S’mores… Entrepreneurs need to be prepared for potentially another turbulent year.

As for startups still seeking to raise new capital in a buyers’ market, it is important to adjust expectations for valuations, in case the investor would simply pass the pitch without even giving it a look. Like how Mastrobuoni warned, and many other investors echoed, “By taking a valuation that you have no chance of growing in the next round, you are setting yourself up for disaster.”