Northvolt v Britishvolt: clarity v confusion in the great electric car battery race

Fast action in global gigafactory race is happening outside UK, as Swedish pacesetter shows

In a fantasy world, the would-be rescuer of Britishvolt would be a consortium that included a car manufacturer or two. The ailing startup would instantly get what it needs most after six months of crisis: endorsement for a battery product that is still in development, plus some , future customers.

At that point, the big political claims made about Britishvolt, its planned gigafactory in Northumberland and “the UK’s place at the helm of the global green industrial revolution”, as the former prime minister Boris Johnson put it a year ago, would start to sound more credible.

Sadly, the deal on the table does not resemble a dream version. The prospective buyer is a consortium led by DeaLab Group, a little-known UK-based private equity investor with backing from interests in Indonesia. Details are sketchy until Britishvolt’s board votes on the proposal on Friday but, as far as one can tell, the Indonesian angle seems to be access to metals needed to produce batteries – lithium, nickel, cobalt and so on. All useful, but, if the consortium has expertise in battery chemistry or in supplying the automotive industry with vital kit, it has so far kept quiet.

Therein lies one reason to be underwhelmed. Another is the fact that Britishvolt is being valued at only £32m, or 90%-plus less than a year ago. Good luck to DealLab but the outline proposal reinforces the fact that the fast action in the global gigafactory race is happening outside the UK.

The one shining exception is Chinese-backed Envision’s plant in Sunderland, which supplies Nissan’s factory next door. Nissan was early into electric batteries and Envision is now planning a big expansion nearby. Even with the extra capacity, though, Sunderland will only reach annual capacity of 38 gigawatt hours (GWh) – enough to power up to 600,000 cars at its peak. The UK car industry is projected to need 96 GWh by 2030 if the many net zero targets are to be met, and Britishvolt had been provisionally marked down for 30GWh of that tally.

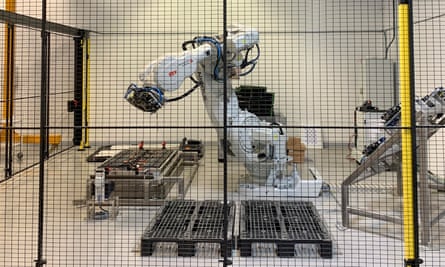

Not for the first time, one wishes Britishvolt was more like Northvolt. Founded in 2016, the Swedish pacesetter has raised $8bn (£6.6bn) in equity and debt over several funding rounds, including a thumping $350m loan from the European Investment Bank in 2020. It delivered its first batteries last year, has one gigafactory in operation and three in the planning stage, and boasts $55bn of orders from big car manufacturers. Those customers include BMW, Scania and Volkswagen, who are also shareholders; and there is a joint venture with Volvo.

The chief executive and co-founder, Peter Carlsson, was a former operational chief at Tesla, working on the rollout of the S and X models, and thus “an incredibly credible” figure to back, says Stewart Heggie of the Edinburgh-based fund manager Baillie Gifford, which first invested in Northvolt in 2020. “You immediately have a founder who is thinking about scale and scaling up.” In the last funding round, Northvolt is thought to have been valued at $12bn.

Don’t write off Britishvolt just yet, says Ian Constance, the chief executive of the Advanced Propulsion Centre, one of the bodies involved in awarding government funding to projects. “They are still in the race and the reason they are still in the race is that they have some excellent technology that has been developed by UK expertise.” In any case, he argues: “We should look at this in the context of growing our battery industry at the rate that demand from the automotive sector takes off. Northvolt is further down the road but all is not lost.”

One hopes that optimistic assessment proves correct but the next 12 months will be crucial for Britishvolt. The site near Blyth, everybody agrees, is perfectly located with the necessary green energy sources. But to get the project firing, customers must commit. Northvolt got them on board early.

For the UK government, the saga should serve as a wake-up call. The Faraday Challenge, launched in 2017 and with a budget expanded to £541m to invest in research and development “to drive the growth of a strong battery business in the UK”, has undoubtedly produced excellent science and facilities. But commercialisation is the tricky part, a perennial UK story.

Ministers surely cannot be blamed for failing to advance the £100m for Britishvolt from the Automotive Transformation Fund. The company simply didn’t get far enough in developing Blyth. New owners, armed with a reported £130m to invest, can take a second run at unlocking the cash. But if 100 GWh of UK capacity – an Envision estimate – is needed to sustain a full UK supply chain, the government would be well advised to find more horses to back. Northvolt is a classic study in first-mover advantage and clinical execution. The UK’s battery strategy needs a boost.