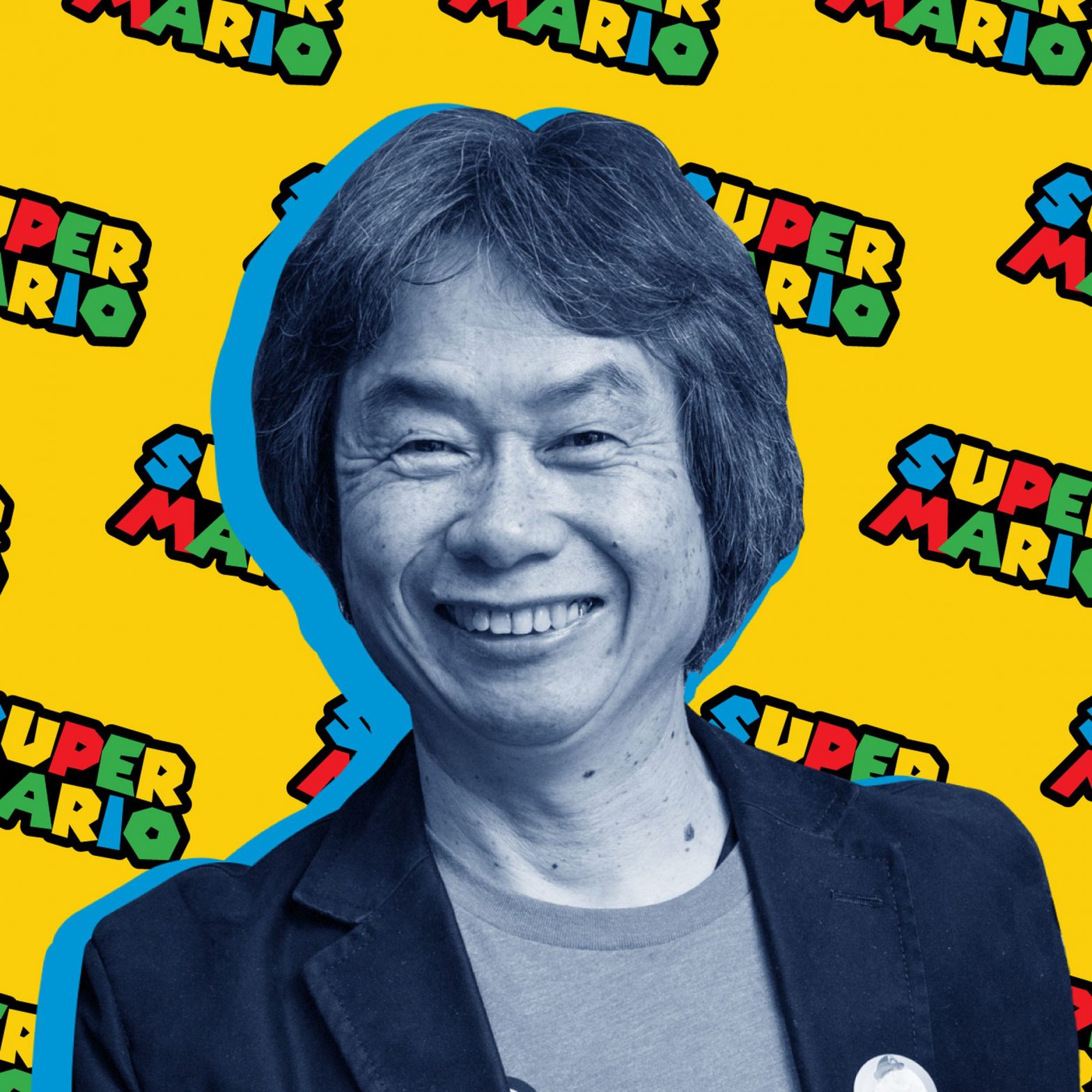

As Super Nintendo World opens up in Los Angeles, the creator of Mario talks about getting back to his roots, and exploring new creative fields.

Share this story

:format(webp)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24432809/236540_shigeru_miyamoto.jpg)

Shigeru Miyamoto is responsible for some of the most iconic virtual worlds in history, from the Mushroom Kingdom of Super Mario to The Legend of Zelda’s Hyrule. But he got his start in something much more tactile, studying industrial design in college before eventually embarking on a career in video games. It’s something he’s missed over the years. “The idea of using my hands to create something really fits well with me,” he says. More recently, he’s had a chance to get back to those roots, working with the team at Universal Creative on Super Nintendo World, which just opened up at Universal Studios Hollywood.

The nostalgia hit him particularly hard when he visited Florida to see where some of the pieces of the theme park were being constructed and test out the texture and materials. “Having these meetings, with the surrounding aroma of factories, was comforting for me,” Miyamoto says.

At 70 years old, Miyamoto is in one of the most experimental phases of his career. Previously the figurehead behind Nintendo’s biggest games, he’s spent the last few years leading ventures outside of the console games the company is known for. He helped lead development on Super Mario Run, Nintendo’s first major smartphone release, and serves as a producer on The Super Mario Bros. Movie, which opens in theaters in April.

And then there are the theme parks. Nintendo partnered with Universal to create Super Nintendo World, an immersive experience that aims to transport visitors to the Mushroom Kingdom. The first edition debuted in Osaka in 2021 (be sure to check out our impressions of the original park), and the Los Angeles location will be followed by subsequent versions in Florida and Singapore.

Miyamoto says that, while Universal was responsible for actually building the parks, the team at Nintendo was very involved in the planning and design. “We had this shared idea of trying to create something new and impressive, and the idea of wanting to create something that’s truly interactive,” he explains. “In that sense, our involvement wasn’t just a matter of reviewing assets or reviewing designs. But really trying to get down to the nitty-gritty of how people are going to experience this, and what their experiences are going to be. And we had a lot of meetings to discuss and nail down what we wanted to accomplish here.”

Despite being a comparative newcomer to the field, Miyamoto says that “there wasn’t any sense of intimidation or fear going into this,” in large part because he fully trusted the team at Universal. Even still, he did have worries about actually pulling it off. “Are people going to be convinced that this is actually the Mushroom Kingdom?” he remembers thinking. “Are they going to feel like they’re in the world? That’s something that you really can’t tell until it’s made. So there was a lot of trial-and-error time to really get the feel for what it is that makes this experience convincing.”

:format(webp)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24440970/VWH_Universal_12_18_2022_SNW_Landscape_3286_v2__1_.jpg)

For Miyamoto, it was also a chance to utilize his experience in a brand-new context. Super Nintendo World is almost like a giant video game: as you explore you can collect coins, search for secrets, and find keys to unlock a specific area of the park. There’s even a real-world Mario Kart ride that’s part theme park attraction, part video game. You zip through a course made up of a bunch of different Mario Kart tracks — you’ll head underwater and across a mesmerizing Rainbow Road — while firing shells, steering to avoid obstacles, and wearing AR goggles that put classic characters into your field of view. It’s all held together by a simple story about Bowser Jr. stealing a golden coin that visitors need to reclaim.

These elements almost all utilize existing technology that Nintendo is familiar with. The Mario Kart ride is powered by augmented reality, something that was built into the 3DS and received widespread adoption thanks to Pokémon Go. Meanwhile, collecting coins and unlocking secrets involves slapping on a wristband that wirelessly connects to the attractions, similar to the NFC technology that powers Nintendo’s Amiibo figures (in fact, the wristband also doubles as an Amiibo figure). These elements aren’t entirely unique for theme parks, but they did allow the team at Nintendo to build on its previous work. “We were able to leverage our experience a lot,” Miyamoto says.

There are differences, of course. Working in the real world means dealing with pesky things like “safety” and “gravity.” You can’t exactly make a working version of Mario Kart 8’s gravity-defying tracks. For the most part, Miyamoto says, this wasn’t an issue. But the real-world nature of the park did change the way he and the team approached the attractions. For one thing, they had to be short, so the team had to really condense the Super Mario experience down into bite-sized moments. But they also wanted the attractions to be exciting even for people who weren’t actively using them.

“There was the idea of having as many people experience and enjoy this space as possible,” Miyamoto says. “So, for example, people who are not even fully on the attraction can still have fun. That’s something we really tried to work around: the limitations. We had to maximize the amount of joy people had, whether they’re actually doing the thing, or watching others.”

That said, there is one element he had to cut out of the final version. Surrounding Super Nintendo World is a towering backdrop that looks like a classic side-scrolling Super Mario game, featuring characters like a stack of goombas and Yoshi moving about. At the very top, on a big hill, lives a traditional Mario flag. “I wish people were able to climb higher towards the Mount Beanpole,” Miyamoto admits. “But obviously there are safety concerns, so that didn’t happen.” He adds, with a laugh, that “it’s unfortunate because the hardware is there.”

And while the design of the LA park is largely the same as its Osaka counterpart, Miyamoto says there were small tweaks made to the entrance, which is a giant green warp pipe, and the exit, in order to make the experience more immersive. “The exit path here requires you to go through a pipe to emphasize the fact that you are going to the non-Nintendo World part of Universal,” he explains. “The park is going to expand to Florida and Singapore, and I’m sure we’re going to have learnings from there as well.”

:format(webp)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24441013/BOWSER_STATUE_0318_W1.0.jpg)

One of the most exciting parts for Miyamoto has been working with new people. Nintendo is a company that historically values outside opinions, often hiring new recruits with no background in games. In the past, Miyamoto has said that working with people with different skill sets is invigorating, and working with the minds at Universal on the theme park offered something similar. “It was very fun,” he says of the process. “I really enjoyed myself.”

Even more exciting: a chance to see fans interact with his work in a new way. Thanks to Twitch and YouTube, it’s possible to watch players enjoy games online, and in the early days of Nintendo’s video game work, Miyamoto was able to observe people in arcades. But there’s something different about the scale of Super Nintendo World. “Back in Japan I was able to enter the world along with people entering for the first time, seeing them reacting with amazement, going wild, and really just all kinds of reactions,” he says. “And to be able to experience that first-hand reaction with them, was a new experience for me and something that I really enjoyed.”

“I tried to hide and be as out of sight as possible,” he adds. “And even though some people did offer handshakes, they were more impressed with the world.” He wasn’t annoyed by the relative anonymity, though. “That’s what I wanted.”