Bailey: BoE’s balance sheet won’t return to pre-crisis levels

Bank of England governor Andrew Bailey tells MPs that he does not believe the Bank’s balance sheet will return to its levels before the financial crisis, even once it has conducted its quantitative tightening (QT) programme.

Treasury Committee chair Harriett Baldwin asks Bailey why the BoE decided last September to embark on QT – the process of cutting its holdings of government bonds bought since the 2008 crisis.

[Reminder: the BoE had bought almost £900bn of UK gilts, in one programme launched after the collapse of Lehman Brothers, and a second after the pandemic].

Bailey explains that the Bank wants to adjust its balance sheet so that it has headroom to do whatever it might need to do in the future. It does not want its balance sheet to simply get larger after every economic shock.

But, the governor insists he does not “envisage” the BoE’s balance sheet returning to where it was before the financial crisis.

The key reason is that QE has created a stock of cash reserves owned by commercial banks which sits on the liability side of the BoE’s balance sheet.

There is “no question” that the banks will need to hold larger cash reserves to ensure prudential stability, and the UK is not alone in this, Bailey explains.

Ramsden: Gilt market turmoil after mini-budget may not have abated

Bank of England deputy governor Dave Ramsden then tells MPs that investors think Britain has a bigger inflation problem than the United States.

That, he tells the Treasury Committee, explains why British government bond yields have risen by more than their US counterparts.

Asked why the spread between interest rates on UK gilts and German bunds, and US Treasury bills, has widened, Ramsden explains:

“My take on this is that there is more of a concern about persistence of inflation (in Britain) and therefore an expectation that our short-term (interest) rate – set by us – will be higher. That feeds through into yields.”

Ramsden also told the Treasury Committee that expectations of US monetary policy have also changed, with the markets starting to anticipate possible cuts by the US Federal Reserve due to problems in the US banking sector.

Ramsden also reminds Conservative MP Andrea Leadsom that high UK borrowing is amother important factor influencing bond yields. The UK’s debt management office is issuing £243bn of debt this year, up from £125bn, he says, due to the fiscal interventions following the pandemic.

Thirdly, Ramsden suggests that the chaos following last September’s mini-budget is still a factor, given the turmoil in the liability driven investment (LDI) pension market caused by the jump in bond yields.

He says:

The third factor which may explain some of those yield differentials is that there may be a bit of a risk premium, or liquidity premium, following on from the LDI episode.

It may be that some of the pension funds and the like have not come back as fully into the market or they’re still adjusting, so you don’t have the same demand for some of those longer term gilts as you had in the past.

That means that the price of them may be lower than it might otherwise be, so the yield is higher.

Q: If monetary policy acts with a lag, as you argue, why is the Bank continuing to raise interest rates when inflation is expected to fall?

That’s a question we spend hours discussing, Ben Broadbent smiles, and there’s a “range of views”.

The issue is how long the ‘second-round effects’ of inflation, on wages and prices, lingers, as an interest rise today will have little impact by the end of 2023.

These rate increases are “causing more pain to people out there”, says John Baron MP (who had just been arguing that rates should have been raised faster).

Broadbent explains that the Bank’s forecasts are conditional on the markets’ interest rate forecasts. So if rates were cut further, inflation would be higher….

Governor Andrew Bailey says the Bank shares Baron’s concerns that inflation could be stickier than hoped, which is one reason it raised interest rates again this month, to 4.5%.

The committee will return to this issue at another session next week.

John Baron MP shoots back that central banks, such as the Bank of England, were behind the curve in waking up to rising inflation.

Had the Bank been more proactive, there might be less pain for people today, Baron suggests.

Q: A month before Ukraine, inflation was on a sharp trajectory higher at 6%, interest rates were 0.5%. Wasn’t that a woeful neglect of duty?

Deputy governor Ben Broadbent point out that interest rates were low for a decade without causing a rise in inflation.

There’s a distinction between causing an inflation shock, and being slow to respond to one, Broadbent insists, pointing to the enormous economic shocks from the pandemic and the Ukraine war.

He explains to the committee how the pandemic led to a shift in demand for goods, globally, pushing up prices.

The key question was how long that would last for – the Bank’s MPC judged that if this demand, and disruption, was caused by the pandemic, then the end of the pandemic would bring it down.

That wasn’t a terrible judgement, Broadbent insists, pointing out that the price of computer chips and lumber has dropped as expected. However, the China lockdown did last longer than expected.

Broadbent explains:

You always have to look forward and ask yourself, how long will this continue?

Baron isn’t convinced, saying it was “quite evident” that inflation, even before Ukraine, would not fall away significantly.

Broadbent disputes it, citing consensus forecasts at the time were that inflation would come down.

“Ah, consensus forecasts…”, says Baron dismissively.

Broadbent point out that these 30 forecasts are from people who spend their lifetime doing this work.

BoE denies QE to blame for UK double-digit inflation

Back at Threadneedle Street, the Bank of England is rejecting claims that its quantitative easing bond-buying programme is responsible for the UK’s cost of living crisis.

Conservative MP John Baron asks the BoE top brass about the link between QE and the UK’s bout of double-digit inflation.

Q: You announced a large expansion of QE in 2020. Was it simply a coincidence that inflation rose from 0.3% in 2020 when you launched your final tranche of QE to over 5% by the end of 2021?

Governor Andrew Bailey points out that the UK economy has been hit by several shocks, including the Covid-19 supply chain shock and the Ukraine war. They both drove up inflation, and aren’t to do with QT.

Bailey tells the Treasury Committee that the UK has not seen a strong recovery in demand since the pandemic, which indicates that QE is not the cause of inflation.

Baron points out that UK inflation was running at 6% before the invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, so “we were already on a steep trajectory”.

Bailey agrees, but says the Bank was weighing up whether the inflationary shock from Covid-19 would be transitory, or not.

If the only shock that the world had experienced was that one [the Covid-19 supply chain disruption] then I think the evidence now suggests it had a limited time period.

Unfortunately, of course, Ukraine came along, and there was no gap between these shocks.

As such, Bailey says we can’t use the word “transitory” to describe these shocks.

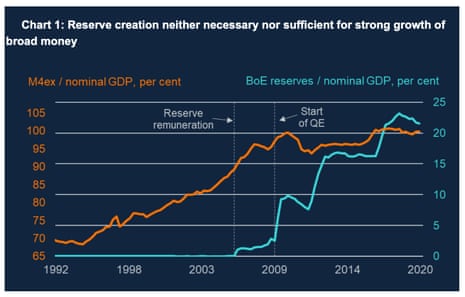

Deputy governor Ben Broadbent points out that the UK had 10 years of QE without an inflation problem, or strong money growth, as did other regions such as the US and the eurozone [he outlined this in a detailed speech last month].

Deputy governor Sir Dave Ramsden tells MPs that the Bank launched more QE after the pandemic began, because it feared the economy would suffer ‘permanent scarring’.

Ramsden voted to end QE early, in September 2021, as he grew more concerned about inflationary risks.

But stopping QE early would have been a surprise, potentially jolting markets.

And cutting QE early, by £30bn, might have taken just 0.2 or 0.3 percentage points off Uk inflation.

Ben Broadbent suggests that market data indicates that the QE conducted in June and November 2021 may have added half a percentage point to UK inflation.

The idea that this is the cause of double-digit [inflation] is not well-supported.

Lloyds suspends AGM livestream amid protests

Kalyeena Makortoff

Lloyds Banking Group has been forced to suspend the livestream of its AGM in Glasgow twice within the first 10 minutes, after climate protesters interrupted chairman Robin Budenberg’s opening remarks.

It’s quite hard to hear what the protesters are saying, since they haven’t been given microphones and Lloyds keeps cutting out the feed, but it’s clear that they’re hitting out at the bank’s contribution to the climate crisis, through certain financial services.

Budenberg has urged them to wait until the Q&A segment, but to no avail, my colleague Kalyeena Makortoff reports.

Climate protesters have also staged a demonstration outside of the SEC Armadillo in Glasgow, alongside staff union Unite – which is separately concerned about the company’s decision to force staff to spend at least two days a week in-office.

Anyone working compressed hours will also have to negotiate new working patterns with managers.

Demo outside the Lloyd’s AGM Glasgow. pic.twitter.com/JU0a313kRX

— Jules ‘navet congelé’ Again (@PalmersJules) May 18, 2023

Unite has previously said the move will do “immediate and tangible damage” to work-life balance and family budgets.

Unite members protest outside the Lloyds Banking Group AGM over management attack on vulnerable staff. New working hours scheme disproportionally impacts women, carers and the disabled working at Lloyds Banking Group.#workinghours #compressedhours @LBGplc pic.twitter.com/PfYtBmnZAi

— UniteFinanceSector (@Unite_Finance) May 18, 2023

Interesting from Bank of England deputy governor Dave Ramsden speaking to @CommonsTreasury just now. He reckons that the next year of quantitative tightening is unlikely to be less than the current £80 billion a year, and may be a bit more. MPC decides in September.

— David Milliken (@david_milliken) May 18, 2023

That follows Bank of England deputy governor Ben Broadbent, who said £80 billion QT was decided last year because of advice that £100 billion might disturb markets.

These figures include maturing gilts – so actual gilt sales (which affect markets more) will vary each year.— David Milliken (@david_milliken) May 18, 2023

Ramsden: QT is like descending a mountain, no decommissioning a nuclear sub

Q: We’ve been told that quantitative tightening is similar to decommissioning a nuclear submarine, so it has to be done extremely carefully because the potential for things to go wrong is enormous….

Deputy governor Ben Broadbent agrees that there are risks, but the Bank has taken them into account. It’s important to avoid selling bonds into illiquid markets, and to conduct QT in a very predictable, very gradual way, he explains.

He tells the Treasury committee that the start of QT was delayed after the crisis in the LDI pensions market last autumn, for this reason.

Broadbent says:

It’s not the case that on the days we’ve sold these gilts there’s been any sort of disruption, and of course we watch for those things very closely.

Deputy governor Sir Dave Ramsden weighs in too, disputing the ‘nuclear submarine decommissioning’ angle.

He tells the MPs that the bank still wants QE to be a monetary policy tool in future.

Ramsden reminds the committee that he worked in the Treasury back in 2009, when then-governor Sir Mervyn King got in touch to say the Bank wanted to start quantitative easing.

It was always seen that QE would not go on for ever, there would always be some QT, he explains.

He compares the bond-buying programme to mountaineering, saying the Bank’s Asset Purchase Facility has grown to a size where the Bank reached “the top of the mountain” (the APF was £895bn at its peak, but is now shrinking under QT).

Ramsden says:

You have to be careful going back down the other side. Because you want to be in a position that you can climb another mountain afterwards, if you have to.

So you always have to be very careful on the descent.

A lot of accidents happen on the descent of mountains, Ramsden points out.

Treasury Committee chair Harriett Baldwin shoots back out that you also run the risk of starting an avalanche….

Bailey insists QT isn’t destabilising markets

Q: Is the Bank of England certain that QT is not having any impact on the market? We’ve had a bank failure since you started… Is it having any inflationary or disinflationary pressures?

Governor Andrew Bailey says he doesn’t see any connection between quantitative tightening and the events in the banking sector.

As proof, he points out that the UK banking system has not experienced stress in recent months – the failure of Silicon Valley UK bank was a “very idiosyncratic issue”, because it was the subsidiary of a bank that failed in the US.

Bailey then explains that UK banks hold £1.5 trillion of “high quality liquid assets”, of which £900bn is reserves at the Bank of England. The BoE’s QT programme should reduce those reserves, with banks looking to hold other high quality liquid assets instead.

But that rebalancing should be “entirely manageable and entirely natural”, he pledges….

Deputy governor Ben Broadbent reiterates that QT is already priced into the financial markets, and those asset price levels are used in the Bank’s economic forecasts.

Broadbent says the Bank can’t tell exactly what impact QT is having, because it has already announced it (so it’s priced in…). But the Bank’s best bet is that it is having a fairly modest impact, maybe just 0.1 percentage point on inflation.

Ramsden: QT could go up a little bit

Q: How might the size of the Bank’s QT programme change in future years?

Deputy governor Sir Dave Ramsden says the Bank won’t definitely plump for another £80bn reduction in its bond holdings next year.

That’s because it would mean lower ‘active sales’ of bonds, given that more of the Bank’s stock of gilts expires next year.

Ramsden says bank analysis will determine the pace of QT:

So there’s the potential for us to go up a little bit. I don’t see us going down, given the experience of the first year.

Q: Why did the Bank set a target of selling £80bn of its stock of government bonds in the first year of QT?

Deputy governor Ben Broadbent says there has to be a number (!), before explaining that ‘active sales of £10bn’ a quarter, on top of the £10bn of bonds which naturally mature each quarter, felt about right.

He reveals that the Bank’s market experts warned that anything over £100bn might disturb market liquidity.

The important point, Broadbent explains, is that the markets have a number for QT which is ‘priced in’ to bond prices (and thus the yields, or interest rate, on those bonds).

On the days of the Bank’s QT auctions, there’s been no detectible moves in bond prices, he insists.

Deputy governor Sir Dave Ramsden denies that the Bank of England is “flying blind” with its QT programme.

Treasury Committee chair Harriett Baldwin replies that the Bank is flying ‘slowly’, and reminds the Bank that the launch of QT was disrupted last autumn (due to the market chaos created by the mini-budget).

Q: You announced the flight take-off, and then almost immediately had to land the plane when you started…

Governor (captain?) Andrew Bailey points out that the Bank hasn’t actually begun – so it delayed the takeoff of QT, rather than returning to the runway.

Bailey insists it was correct not to launch quantitative tightening operations in disturbed market conditions last autumn (the Bank waited until the start of November).

And he denies that the Bank contributed to the disturbed markets, with its plan to sell some of its QT bonds back to investors.

Bank of England governor Andrew Bailey tells the Treasury committee, “QT is not an active monetary policy tool,” that should be left to Bank Rate. pic.twitter.com/R7pFEvspcC

— Damian Pudner (@Broomscroft) May 18, 2023