We read everywhere that the built environment accounts for 40 per cent of global GHG emissions, but what exactly does it mean at a granular level? Unless we understand the overall spectrum of these emissions, we cannot plan an integrated approach to decarbonizing the built environment.

Even before any work starts on a project, site selection in the first area can impact emissions, primarily if there is a land use change that results in deforestation or appropriation of green agricultural land. Building within urban areas, thoughtful enhancement of urban density, and going brownfield are the simplest ways of avoiding these emissions.

One of the most hard-to-abate components of built environment emissions comes from materials that make up the building, primarily cement, concrete, steel, glass, aluminium, other metals, plastics, wood, etc. As per the NIUA RMI report, embodied emissions account for 10 per cent of emissions from the building sector and considering the improvements made in operational carbon and the work to be done in embodied carbon, the emission due to embodied carbon could reach as high as 50 per cent.

Considering the life span of the building as 50 years, it is essential to avoid the lock-in of inefficiency by carefully selecting low embodied carbon material that can also enhance thermal comfort. Unlike operation carbon, it is tough to retrofit the building materials once the building is constructed. The embodied carbon relates to the emissions that arise from the extraction, processing and transportation of the materials therefore are also called supply chain emissions. It makes it even more difficult for designers to abate emissions from this segment due to the limited influence on material manufacturers and suppliers. In addition, building repairs and material used during maintenance also contributes to emissions, and high maintenance and poor-quality construction add to these emissions.

In the case of operational energy, the first approach focused on bringing the energy requirement down through various interventions. Typically, around 40-80 per cent of energy is consumed in an air conditioning system to provide thermal comfort to the occupants. Multiple strategies to reduce the cooling requirement in a building include passive design (orientation, shading, window-to-wall ratio), building materials with higher thermal performance for wall, roof, and glass, defining the adequate adaptative comfort depending upon the occupants followed by precooling of fresh air. Around 25 per cent of cooling demand can be reduced through these interventions.

The second approach to reducing operational energy consumption focused on serving the energy needs through energy-efficient equipment. The Bureau of energy efficiency has already defined the standard and labelling program for various appliances like room air conditioners and others. The Global Cooling Prize demonstrated technologies with five times less climate impact (5X) than traditional room air conditioners (RACs). These can reduce India’s peak electricity by 400 GW in 2050.

However, scaling these advanced 5X-efficient RACs requires the following:

- Rewriting rating test standards to account for the full range of cooling, including humidity

- Collaboration with manufacturers to accelerate the transition to leapfrog efficiency

- Bulk purchasing and other market-transformation initiatives

- Mass-market awareness of benefits, personal and societal.

Apart from the emissions related to the demand side, it’s essential to understand the emissions associated with the supply side, mainly linked to the fuel used to generate the electricity for the buildings. Coal still constitutes 70 per cent of the Indian economy, with grids in India are still heavily relying on fossil fuels. The Indian government has recently submitted its revised NDC, which is targeted to achieve about 50 per cent cumulative electric power installed capacity from non-fossil fuel-based energy resources by 2030. Through various strategies of RE deployment, including installing on-site rooftops and remaining through off-site procurement, emissions from the building can be bought down to zero. On-site plants also help reduce peak loads on the grids, further spiralling the growth in clean energy.

Despite all these efforts, some emissions may remain and require carbon capture technologies, energy storage and other innovations. However, there is still room to help avoid emissions through initiatives such as afforestation, green mobility, etc., that can be integrated into the built environment and urban design.

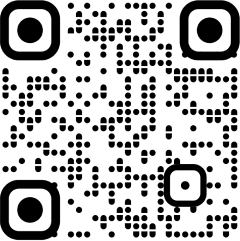

The water flow diagram below shows different strategies under embodied carbon, operational carbon, and clean energy to achieve a net zero future. It represents a typical trajectory towards decarbonization. The net-zero urban accelerator launched by Lodha in collaboration with RMI focuses on the various strategies shown in the diagram with an urgency to achieve carbon neutrality. We believe this approach enables us to develop a demonstrable urban development template that proves that growth decoupled from emissions is possible.