In 1990, John Romero, John Carmack, and Tom Hall were working at Louisiana software maker Softdisk. There, they had an idea that would change PC games forever.

Share this story

:format(webp)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24792314/Screen_Shot_2023_07_17_at_8.13.56_AM.png)

I was speechless.

I know that may be hard to believe. I talk passionately about games to anyone who listens whether it is about programming techniques, upcoming games and consoles, or the latest game I am into. Softdisk even had a conversational atmosphere.

Still, on September 20th, 1990, I was at a total loss for words. But my silence wasn’t the real story. The reason for my silence — that was the real story.

In the space of about one second, at the age of almost 23, I had glimpsed my future, my colleagues’ future, and the future of PC gaming, and that future was phenomenal.

Moments before losing my capacity to utter a single word, I had arrived early to an empty Gamer’s Edge office to find a 3.5-inch floppy disk on my keyboard with a note from Tom instructing me to run the program on the disk. I inserted the floppy.

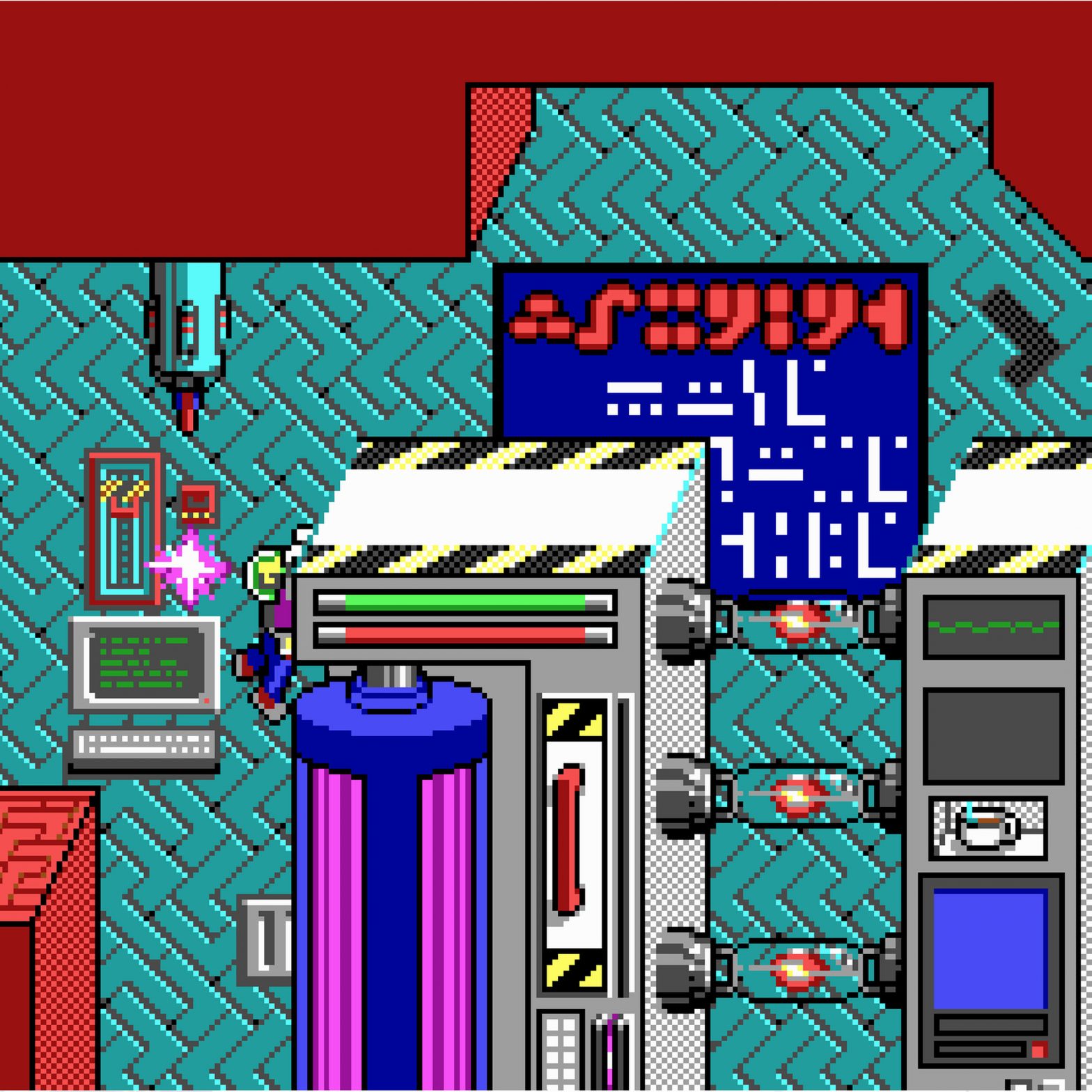

I was greeted with a brown title screen announcing, Dangerous Dave in “Copyright Infringement.” One side of the screen had a circular portrait of Dangerous Dave, a character I had created a couple years earlier, in his signature red baseball cap. The other side had a portrait of a judge bedecked in a powdered wig holding up a gavel. I took in the image and wondered how Dave was going to interact with the halls of justice. I had no clue where this was going.

I hit the spacebar and got the shock of my life.

A familiar video game lit up my PC screen. I was looking at a replica of Super Mario Bros. 3: the billowing white cloud characters, the green shrubs, the construction blocks, and rotating gold coins. But Super Mario didn’t exist on the PC, because the technology that powered it didn’t exist on the PC. It existed only on the Nintendo Entertainment System and a couple of the ’80s’ best computers, the Atari 800 and the Commodore 64. These systems had the custom chips to handle two-dimensional side-scrolling. PC games, due to a dearth of graphics support and processing power, had been restricted to static screen games and chunky scrolling — until Carmack created smooth vertical scrolling just a few days earlier with Slordax.

Now I looked at Super Mario Bros.’ Mushroom Kingdom and wondered what it was doing on my PC screen. I also noticed Dangerous Dave standing at the bottom of the screen. The character I created two years earlier who was inspired by Super Mario Bros. was now inhabiting the Mushroom Kingdom. I laughed. That was the copyright violation of the title, but how far did this parody go?

I hit the arrow key to move Dangerous Dave and find out.

What I saw destroyed me.

The scenery on screen was changing, moving. As Dave walked and bounced his way into the game, moving right, new scenery and new challenges emerged. Everything scrolled smoothly, seamlessly, continually to the left. I hit the direction keys, moving him back and forth and up and down. As much as it looked like I was playing, I wasn’t. I was processing the enormity of what I saw.

You know how in Star Wars when the Millennium Falcon goes into warp speed and the stars start whizzing by?

That’s how I felt.

Teleported into the future.

I had to stop and process what I had just witnessed, what Carmack had done. I was sure Tom had done the nuts-and-bolts recreation of Super Mario Bros. 3’s gamescape, which was funny and cool, but the horizontal scrolling that knocked me out? That was clearly all Carmack. The two of them had created this little program as a joke. As a fun way to tell me that Carmack had figured out a cool programming trick, that he took on my challenge and delivered.

Only this wasn’t just a cool trick. This was a revolution.

For me, the implications of horizontal scrolling were so vast it was hard to fathom. I saw the entire universe of PC gaming expand in that split second. Horizons were no longer finite, no longer limited to the fixed dimensions of a computer screen. I had been immersed in the PC game market for a good two years now. My goal had been to understand every game, all the technology, all the programming tools. I had immersed myself in the PC because I needed to know where the leading edge was. When I saw Dangerous Dave moving effortlessly to the right, I knew the leading edge was right before my eyes. I mean this quite literally. I knew what I witnessed, and I knew this was our future. Ironically, Carmack and Tom didn’t.

I knew what part of the video hardware Carmack had to use to create the side-scrolling effect, but he had figured out another optimization that reused background graphics so that the PC could read, render, and react with maximum efficiency. Remember that processing power and available memory were a fraction of what’s standard today. Carmack had created a rendering engine that rewrote the rules of the game, of all games, and yet he didn’t realize it. In fairness, nobody else did either.

The ability to program games that move so smoothly on the horizontal axis within the game world was earth-shattering technology. It meant we could write games for the PC that rivaled the games created for gaming systems like Nintendo, Sega, and Atari without the need for their specialized hardware. Players didn’t need to invest in a new console! All they needed was a PC and the game files. Nowadays, this is what venture capitalists mean when they talk about “disruption.”

When Dangerous Dave moved, he wasn’t just moving right in pursuit of the gold coins of Mario’s kingdom — he was stepping into a completely new future for PC computer gaming, and we were going to step with him. Not just into a new technological and gameplay standard, but into entirely new lives. I knew right then that we were going to make groundbreaking games. We were going to be the team to follow. Like Wozniak. Like Nasir. Like Budge. Like my game dev heroes. We were going to build our own game company!

I put the disk back into the drive and let it fly, lifting my voice over the beeps and blurts of the soundscape Tom had assembled. “This is the coolest fucking thing ever. We need to get out of here. This is our ticket.”

Jay Wilbur, the guy who had known me longer than anyone at the company, walked by our office door as I was talking.

“Hey, what’s up guys?” he said.

“Jay, you saw the demo, right?” I said.

“Yeah. It’s really cool.”

“Dude, it’s beyond cool. It’s ‘we’re out of here cool’ is what it is.”

Jay snorted at this as if he thought I was just spouting off, hyping something up, which he’d seen me do dozens of times in the four years we’d known each other.

“I’m dead serious, Jay.”

He must have heard the commitment in my voice and concluded I was not blowing smoke, because he closed the door.

I laid out my vision: “We have to get out of here. That’s the plan. We’re going to keep working together, and we can totally make some unbelievable games, but we need to get out of here. Side-scrolling means we can create PC games that rival the games of the biggest-selling videogame companies in the world. We have the perfect team right here in this room. We need to refine this and develop our own games for PC. If we do, they will be superior to every single PC game out there. Think about it. There is not a single game on PC that lets you move like this, and the market for PCs is exploding! We can do this. We have to do this.”

Everyone heard me loud and clear. It made sense. Jay believed something big was happening, too.

“This is what I think,” he said. “We need to take this to Nintendo right now. Straight to the guys at the top and get a deal to port it to PC. Then we are talking serious money that can fund other development.”

It was the obvious play, the one I’d thought of instantly when my head was exploding with ideas. Now Jay had expressed it and confirmed my thoughts. Everyone was on board. We just had to figure out how and when to do what needed to be done. Continuing to work for Softdisk, we went into heavy stealth mode with our new tech. We were all work all the time, with only sporadic breaks to play Super Mario Bros. 3, Lifeforce, or The Legend of Zelda.

With our mission complete, Jay sent our demo to Nintendo with a request to let us develop the game for PC. Three weeks later, Nintendo turned us down. They wanted to keep their intellectual property exclusive to their proprietary system. This, of course, made perfect sense, even if it didn’t initially work in our favor. Fortunately, I stumbled onto a terrific plan B while making the Super Mario Bros. 3 demo. I had gotten plenty of mail from gamers over the years, especially when I was publishing games in inCider and Nibble. Some of them were people having difficulty typing in the source code of my games from magazines, and some were complimentary. Since I’d arrived at Softdisk, though, my work wasn’t exactly front and center. The disks we mailed out every month didn’t have my address on them. So I was surprised when I started getting fan letters sent to me via Softdisk.

When the first one came, from somebody named Scott Mulliere, I pretended to make a big deal of it, showing it off like I was somebody’s idol, but, obviously, I was honored. Scott “loved” my game and pronounced me “very talented” and himself “a big fan.” As a game developer, particularly in the 1980s and early 1990s, it was rare to have any kind of fan interaction, and so I was grateful that people played my games and liked them enough to write me. Behind the barricades at Softdisk, mail was exceedingly rare. In fact, some companies, wary of talent being poached, made it hard to reach programmers. A few more “fan mails” followed Scott’s letter. Some of them asked me to write back or even call collect. I taped them on the wall near my PC, but I didn’t give them too much thought. Since I was so busy, I didn’t feel the urge to write back.

Right around this time, I read a story in PC Games magazine about a new game distribution model that was paying off for a guy in Texas named Scott Miller. The article mentioned his address on Mayflower Drive in Garland, Texas. That rang some bells. Who did I know in Garland, Texas? I racked my brain and then glanced at the letters on my wall. Every one of them was from Garland. Every one of them had the exact same address. Every one of them was from an allegedly different guy.

What the hell was going on? Who was sending me these letters? How the hell had I not noticed this before?

I didn’t understand what his problem was. Was he a freak? A stalker? A practical joker? Was he trolling me? I immediately wrote him a long, nasty response, but I cooled off and reread the letters on the wall, noting the invite to call collect and make contact. Bizarre, for sure, but he must have had a motive behind his madness. So, I enclosed another letter along with my more reactionary first letter, telling him that I was mildly intrigued by his strange method of making an approach. I included a phone number at Softdisk where he could reach me.

Soon after that, he got in touch.

“Oh my god. FINALLY! John Romero!” he said when I picked up the phone.

“Who is this?”

“Scott Miller. We so need to work together.”

I thought of saying some of the nastier things I wrote in my first letter, but settled on something less confrontational. “Dude, what was with those letters you wrote me? All those different names? It’s unbelievable. Can you — ”

“Never mind the letters. I had to write that way to make sure they got to you. It’s hard to make contact with programmers, but forget all that. What I really want to do is talk about you making games for me.”

After that, he backed up, and we got on track.

He told me his story, focusing primarily on the new company he’d created, Apogee, and how he had solved the computer gaming distribution puzzle — a challenge for any independent game startup — with a disk- and BBS-based grassroots solution.

He didn’t exactly put it in those terms, but that is what it amounted to. In the fall of 1990, there was no Steam, Epic Games Store, or online App Store. If you wanted the latest games, you ordered them via mail order, or you went to smaller retailers like Electronics Boutique, ComputerLand, Egghead, or Software Etc., if you were lucky enough to have any one of those in your town. In bigger cities, everyone who wanted games went to large computer stores like CompUSA or Babbage’s, found the game section, and bought what are now called big box games off the shelf. The managers of these outlets organized the games by genre, and in doing so, organized the industry by genre, too. The world of downloading games online was in its infancy on BBSs but was gaining popularity.

Scott had adapted the shareware model — where developers made applications or games available for free download and hoped users would appreciate their work and send them money in return. Scott had been writing games since he was a teenager, mostly text-based quiz and adventure games. Instead of giving the whole game away, Scott decided to post a sample version of a game on bulletin boards and Usenet groups. The idea was to hook users and then make them pay for the complete version. When they finished the free sample, a screen popped up with Scott’s address and instructions to buy the rest of the game from him.

He said he was making a fortune — thousands of dollars a week on a roguelike game called Kroz, a game mentioned in the PC Games article. He gave away the first episode of the game, “Kingdom of Kroz,” and the thousands were coming from people who wanted to complete the trilogy with “Caverns of Kroz” and “Dungeons of Kroz.” He’d even given the first episode away on Big Blue Disk #20, but that was before I got to Softdisk.

The reason he wrote me those letters, he told me, was that he wanted me to make a clone of Pyramids of Egypt for Apogee. “It’s a perfect shareware game and will sell like crazy.”

“We can’t do that. Softdisk owns Pyramids, Scott.”

But I saw an opening for our stealth plans and went for it.

“You wouldn’t want Pyramids anyway. We’ve got something way better. You have no idea how cool our current game is,” I told him. “It is light years cooler than Pyramids. I’ll send you a sample. You’ve never seen anything like it on the PC.”

“Then I want to sell it.”