/

Scientists are racing to relocate corals from dangerously hot ocean waters.

Share this story

:format(webp)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24821203/Credit_The_Reef_Institute___Corals_safe_in_living_gene_bank_at_The_Reef_Institute_colorcorrected__1_.jpg)

Federal authorities and scientists are scrambling to relocate corals from Florida’s coastlines before a killer heatwave wipes them out.

The water is unbearably hot for corals, animals whose bodies form the reefs that coastal communities and other marine life depend on. Corals get their color from a symbiotic relationship with photosynthetic algae that provide them with the nutrients they need to survive. Unusually high temperatures, as the Atlantic Ocean is experiencing this summer, drive that colorful algae away. It’s a problem called coral bleaching that, if it lasts too long, ultimately kills corals.

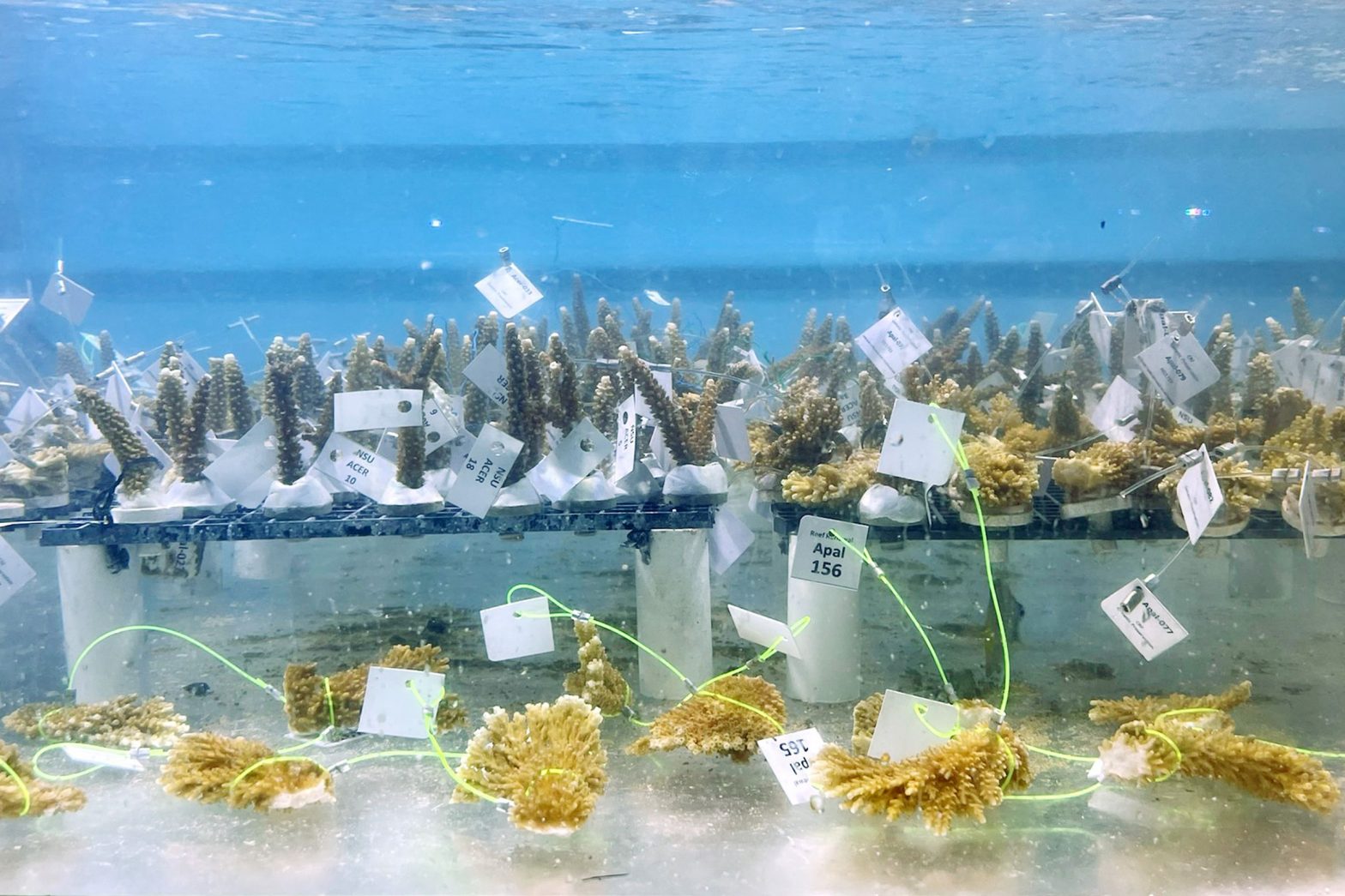

Anticipating a mass die-off, scientists have had to resort to moving corals from the sea to climate-controlled labs. “Our hands-on restoration work is now all that stands between these animals and their extinction,” Jessica Levy, director of restoration strategy at the Coral Restoration Foundation, said in a July press release.

The move is supposed to be temporary, “for rehabilitation and safekeeping,” according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), which works on coral reef conservation with the foundation. But the heat has been devastating even to long-term efforts to restore reefs that were already struggling.

Waters surrounding the southern Florida Keys haven’t been this hot since satellite record-keeping began in 1985, NOAA said in another press release on Friday. Corals in the region started bleaching in mid-July, and it has escalated quickly to “mass coral bleaching and mortality.”

The bleaching threshold, when water temperatures rise high enough above the usual summertime maximum to trigger bleaching, is 87.13 degrees Fahrenheit (30.63 degrees Celsius) around the Florida Keys. Water temperatures in the area have been above that bleaching threshold since mid-June and got as high as 92.48 degrees Fahrenheit (33.60 degrees Celsius) on July 13th.

:no_upscale():format(webp)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24821153/ET_bleaching_keys_July2023.gif)

As part of rescue efforts with the foundation and academic researchers, NOAA is working to collect two living fragments from each genetically unique staghorn and elkhorn coral within Florida’s coral reefs. One fragment will be sent to the Mote Marine Laboratory in Sarasota and the other to the Reef Institute in West Palm Beach. Conservationists have been growing corals in labs and ocean nurseries with the goal of eventually planting them back in reefs.

Unfortunately, both nurseries and reefs where corals were previously planted are barely hanging on in the heat. Thousands of coral nurseries have been relocated to tanks at the Florida Institute of Oceanography’s Keys Marine Lab. That’s “hopefully for just the short-term,” NOAA said on Friday.

The scene at some conservation sites in the ocean has been heartbreaking. “What we found was unimaginable — 100% coral mortality,” Phanor Montoya-Maya, restoration program manager at the foundation, said in a press release after their team visited the Sombrero Reef on July 20th that it has been working to restore for more than a decade.

The last time the region saw a major mass bleaching was in 2014 and 2015, part of a three-year global crisis for corals caused by record ocean temperatures. Sea surface temperatures and coral heat stress this year are already well above where they were during that disaster or at any other time since 1985. The heatwave also started much earlier this year, and there’s a 70 to 100 percent chance that the extreme temperatures last through September and October in the North Atlantic, NOAA says.

Florida’s coral reefs were already in trouble; healthy coral cover in the Keys has declined by 90 percent since the 1970s. Even so, the remaining barrier reef — spanning some 225 miles — is crucial to the environment and local economy. The reef is home to thousands of different species of animals and plants, and it gives coastal communities an important buffer from storm surges and high tides.

That’s why conservationists are determined to prevent more damage and potentially reverse some of the harm human activity has had so far on reefs. They’ve suffered from pollution, boating mishaps, overfishing, and of course, climate change, which could kill off 99 percent of the world’s coral reefs if global climate goals under the Paris agreement aren’t met.

“Despite the devastation, we remain hopeful and determined,” Montoya-Maya said. A little further north, where the water isn’t so hot, corals around the Upper Keys have fared better this summer, giving conservation teams time to act. “We are now rescuing as many corals as we can from our nurseries and relocating key genotypes to land-based holding systems, safeguarding our broodstock – potentially, the last lifeline left many of these corals,” said Montoya-Maya.