The California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) is scheduled Thursday to make a high-stakes vote that will determine the commercial future for autonomous vehicle technology companies Cruise and Waymo — not to mention any other AV company with aspirations to launch commercial robotaxi services in the state.

Cruise and Waymo already offer limited commercial services in San Francisco. If the CPUC grants Cruise and Waymo its final permits, the two companies will be able to charge for all rides, expand hourly operations and service area, and add an unlimited number of robotaxis to their fleets.

California is a paradox for the AV industry. The state is a hub of tech activity with large concentrations of AV engineers located in and near the Bay Area, making it a natural place for development and testing. It gets tricky, however, once a company wants to deploy commercial operations in California, a state with some of the strictest autonomous vehicle regulation in the country.

A “no” vote would certainly delay, if not completely derail, Cruise’s and Waymo’s plan to launch commercial operations in the state. That could accelerate plans to expand in other cities like Phoenix, where Waymo has long operated and where Cruise is starting to push into.

The CPUC’s decision Thursday could also influence how other cities choose to regulate the growth of AVs.

Developing, testing and deploying AV tech isn’t cheap, and the only way to reach positive unit economics is to scale. Waymo has already had to pull back on operations this year after Alphabet issued a slew of layoffs in the first quarter. In July, the company shut down its self-driving trucks program to shift all its available resources to ride-hailing.

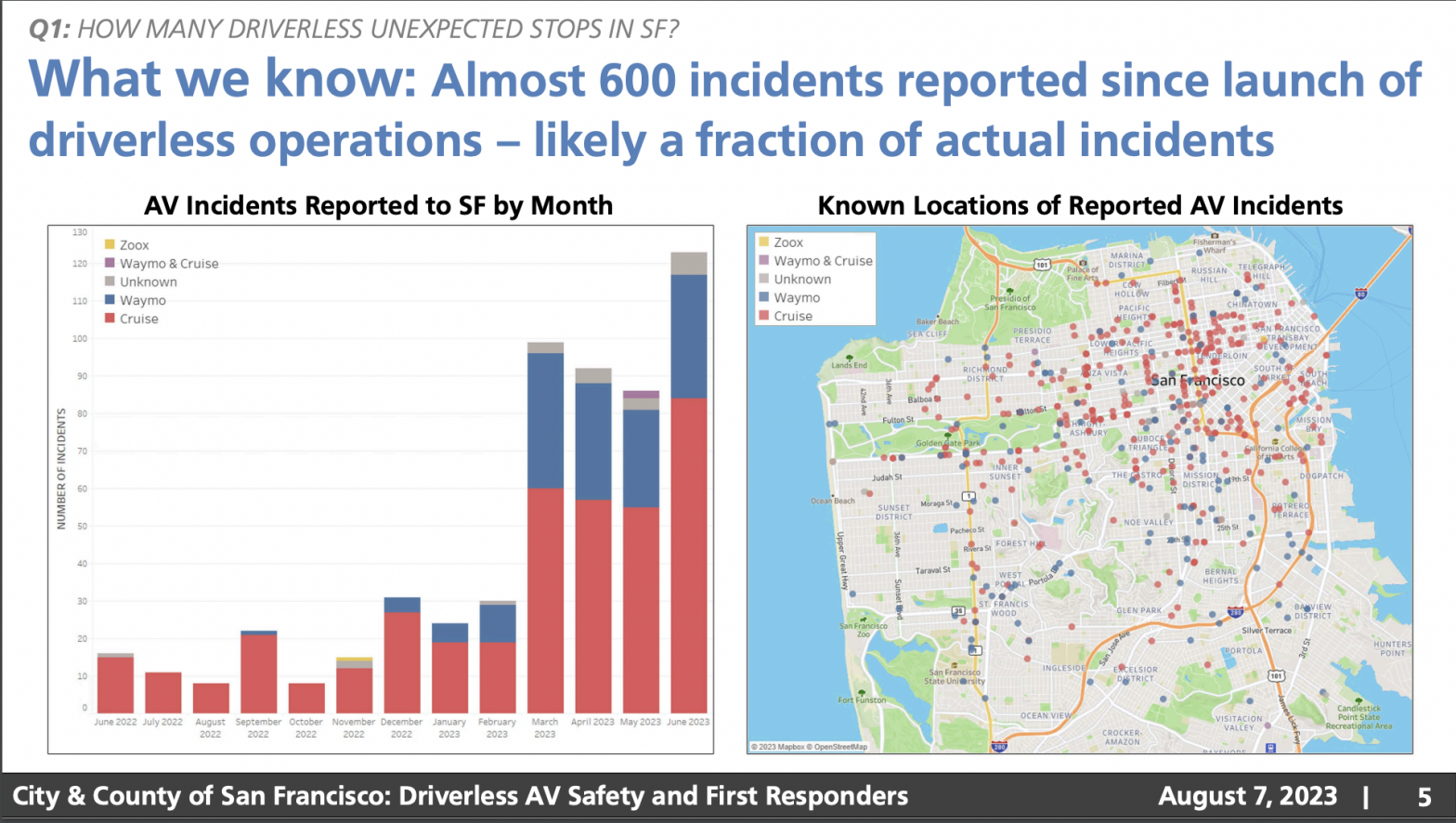

Back in May, the CPUC had all but granted the expansion permits, then delayed the final vote twice amid mounting opposition from city agencies and residents. Since AVs hit the streets of San Francisco, there have been numerous instances of vehicles malfunctioning and stopping in the middle of the street — referred to as “bricking” — blocking the flow of traffic, public transit and emergency responders.

“This technology is still in development and is simply not ready to operate 24/7 in the city,” reads a statement from the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency (SFMTA). “Several minutes of driverless AV stalled on Muni rail tracks can cause several hours of disrupted transit service.”

Opponents to the expansion are urging caution and incremental growth. They’re also calling for more transparent data sharing from the AV companies. Today, AV companies are only required to report collisions and not the many incidents of bricking.

Cruise and Waymo argue that SF’s streets are unsafe and that AV technology can save lives. Cruise has said that, in simulation, its AVs were involved in 92% fewer collisions as the primary contributor and 54% fewer collisions overall when benchmarked against human drivers in comparable driving environments.

Getting into the data

Screenshot from CPUC meeting displaying AV incidents reported. Image Credits: SFFD, SFPD, SFMTA

During a meeting with the CPUC on Monday to discuss how AVs interact with first responders, Waymo said it has about 100 vehicles on the road at any given time, and about 250 on its equipment list. Cruise said it has roughly 300 vehicles operating at night and 100 during the daytime in San Francisco.

The companies also shared data on instances in which someone from their team had to go and physically move a bricked AV, which they referred to as a “vehicle retrieval event” or VRE.

According to Cruise’s data, from January 1 to July 18, 2023, there were 177 VREs, and of those, 26 occurred when a passenger was in a vehicle. Only two VREs involved first responders, and the average resolution time was clocked at 14 minutes.

Waymo had a slightly better go of it, but that could be because the company has fewer vehicles on San Francisco’s roads. From January 1 to June 30, Waymo recorded 58 retrieval events and said it averages 10 minutes to retrieve bricked vehicles.

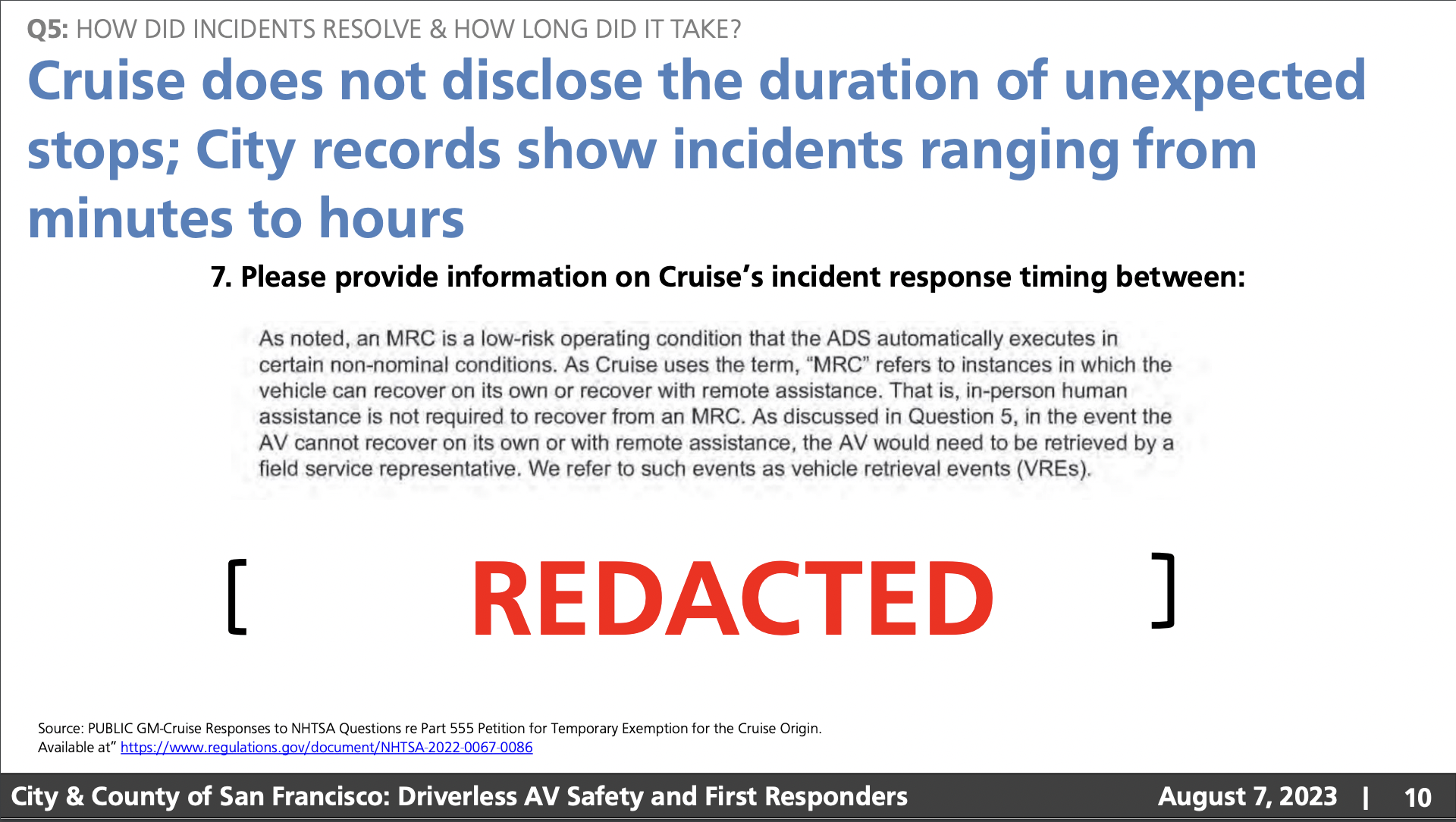

City officials have said that VREs only make up a subset of the total number of unexpected stops but that it’s difficult to know exactly how many of such stops there have been because Cruise and Waymo don’t share their data, and any data they do share is redacted.

“Given that we do not have actual data, what we have is information from reports that have been made by members of the public, by city employees, by firefighters, by transit operators,” said Julia Friedlander, senior manager of automated driving policy at the SFMTA, at Monday’s meeting with the CPUC. “And what we have seen is that things are not getting better. The monthly rate of incidents has been growing significantly over the course of 2023. You’ll see that June was the month with the highest number of incidents of all kinds.”

Between April 2022 and April 2023, the SFMTA collected a total of 261 incidents involving a Cruise vehicle and 85 incidents involving a Waymo vehicle. Those incidents include multiple types of driving behavior, including unexpected stops, erratic driving, issues with pickup and drop-off, and collisions.

According to the San Francisco Police Department, between June 2022 and June 2023, Cruise vehicles were involved in 30 collisions, six of which resulted in injuries. Waymo vehicles had two collisions, one of which resulted in an injury.

San Francisco Fire Department (SFFD) chief Jeanine Nicholson said Monday that the SFFD has recorded 55 reports of interference in 2023. Nicholson said these include things like unexpected stops in front of fire stations that prohibit emergency vehicles from responding to incidents in a timely manner and vehicles coming into scenes in an “unsafe and unpredictable manner.”

Blocking first responders and other risks

Screenshot from CPUC meeting displaying two instances when AVs did not respond to first responders. Image Credits: SFFD, SFPD, SFMTA

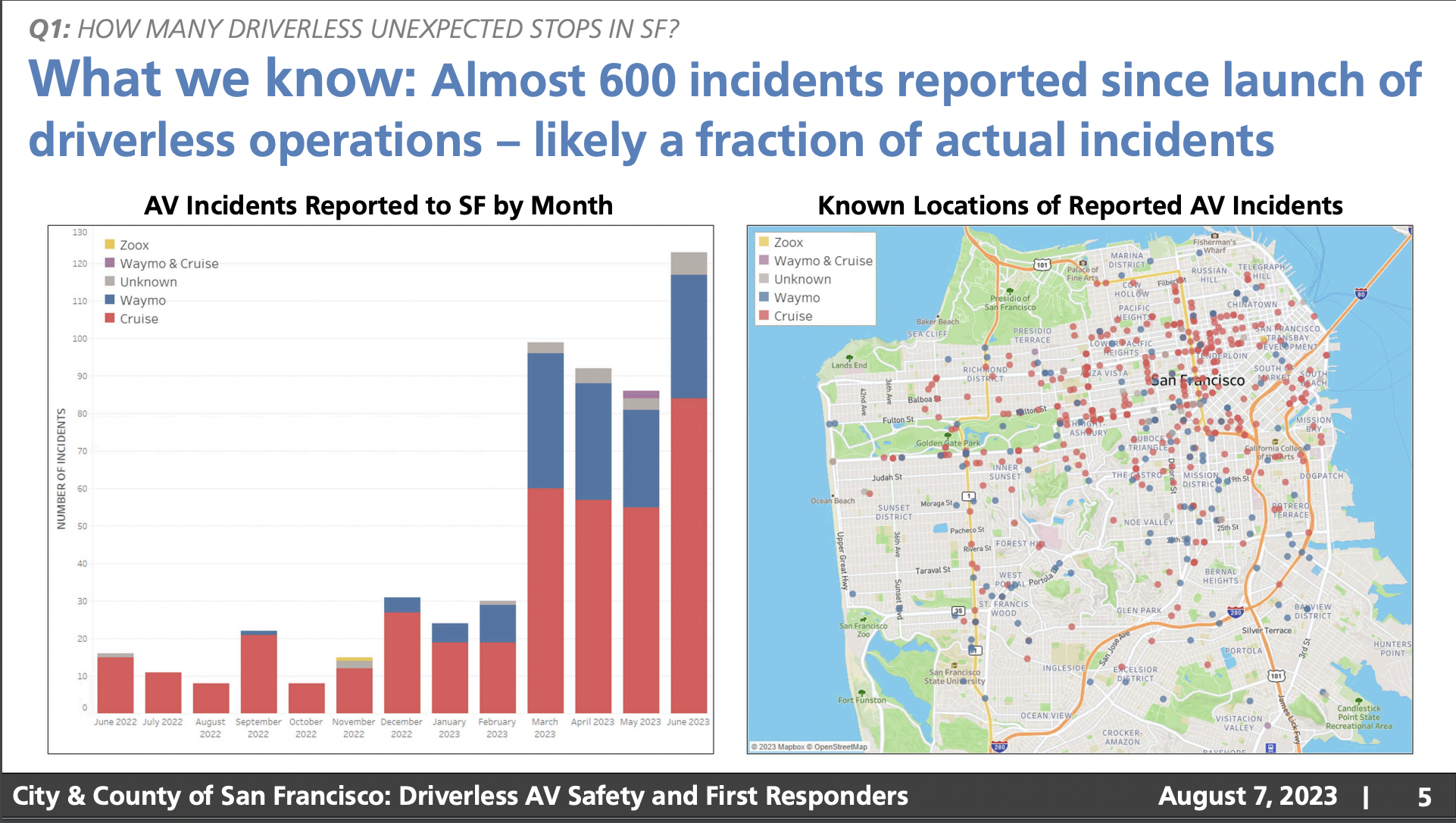

The SFFD has reported incidents of AVs’ rooftop sensors getting entangled with electrical wires after the cars ignored warning signs and yellow emergency tape; blocking firehouse driveways; sitting motionless on one-way streets and causing emergency vehicles to back up while responding to incidents; pulling up behind fire trucks with emergency lights on and interfering with firefighters unloading ladders; and entering an active fire scene and parking on top of a fire hose.

During Monday’s meeting, Nicholson said that the SFFD and other city agencies had been told by Waymo and Cruise that if an AV bricks in an active emergency zone, first responders can get in touch with their customer service and AV field support teams, or they can get in and take over the vehicle to move it.

“It is not the responsibility of my people to get in one of your vehicles and take it over,” Nicholson said. “It is the responsibility of the autonomous vehicle companies to not have them impact us in the first place . . . our folks cannot be paying attention to an autonomous vehicle when we’ve got ladders to throw.”

Cruise is working to get regulatory approval to deploy its purpose-built Origins, which are built without steering wheels or pedals. Those would be impossible for a first responder to move without towing them away.

“If we are blocked by an autonomous vehicle, a fire can double in size in a minute that could lead to more harm to the people in that building and to the housing overall, and my first responders will be going into a more advanced fire,” Nicholson continued. “It can also lead to worse outcomes on a medical level.”

Jarvis Murray, for-hire transportation administrator for the Los Angeles Department of Transportation (LADOT), pointed out Monday a range of other risks. Waymo has begun testing its AVs in Los Angeles but will require an additional permit from the CPUC to start a commercial service there.

In addition to blocking traffic and first responders, Murray said that LA agencies were concerned about technical failures like software glitches or sensor malfunctions leading to accidents or unexpected behavior, as well as cybersecurity threats.

SF agencies ask CPUC to halt on 24/7 permit for now

City agencies have complained that they do not receive enough data from AV companies regarding unexpected stops. Image Credits: SFFD, SFPD, SFMTA

Most of the city agencies that spoke during Monday’s meeting with the CPUC agree that AV technology has the potential to save lives, improve traffic and reduce greenhouse gas emissions — just not quite yet.

Before issuing any permits, the SFMTA argued that the CPUC should collect better and new AV data (including unexpected stops and duration of the stops) and create a performance evaluation framework and methods for analysis of the data. The CPUC could then authorize the incremental expansion of AV services using that framework and the data collected.

“In our view, two-way data information sharing would allow cities to note areas where these unexpected stops continuously occur, and this would allow us to evaluate the street design in that area,” said Murray of LADOT. “But without this type of data and information, cities are frankly powerless to assist the companies and the communities and alleviate these concerns.”