Hundreds of women have filed lawsuits against Uber claiming the company hasn’t done enough to prevent instances of sexual assault by drivers. Now a panel of judges has ruled that more than 80 cases can be consolidated into federal court.

The stakes are high for both parties with implications extending to future Uber riders and drivers. The outcome of the case could result in sweeping changes to Uber’s platform, which plaintiffs argue will reduce sexual assault and also raise new concerns over privacy.

The upshot? Technology lies at the center of this very human story.

Uber has attempted to address sexual assaults by drivers — which the lawsuits claim Uber has known about since 2014 — through new safety features in its app, like a 911 button and the ability to share location with a friend. Yet survivors, and their attorneys, say that response has been inadequate, and they’re calling for better technological solutions like in-vehicle surveillance cameras.

Aside from the 911 button and location-sharing feature, which were both introduced in 2018, Uber has added other features to the app over the last five years. In 2021, Uber introduced a feature that allows riders and drivers to record audio during a trip. The following year, Uber launched a pilot to provide passengers with live help from an ADT safety agent, as well as PIN verifications to ensure passengers are connected to the correct driver.

Rachel Abrams — a sexual assault attorney and partner at law firm Peiffer Wolf Carr Kane Conway & Wise, one of the law firms working on the multidistrict litigation, who filed the petition to consolidate the various actions in federal court — argues the app-based solutions are half-measures that haven’t quelled instances of sexual violence against passengers on the platform. Mandatory in-vehicle cameras in Uber cars is “essential for safety,” she says.

Uber told TechCrunch it cannot comment on pending litigation but said it remains committed to the safety of all users on its platform.

In-vehicle cameras as a deterrent

Abrams cited data from studies of taxis equipped with in-vehicle cameras, which she says has drastically reduced instances of sexual assaults against passengers, as well as assault of passengers against drivers.

“These are predatory, opportunistic drivers taking advantage of vulnerable women, so if they’re on film, they likely wouldn’t commit the crime,” Abrams told TechCrunch.

Uber didn’t respond to TechCrunch’s request for more information about why it hasn’t mandated the use of cameras in ride-hail vehicles, but as with any surveillance, there are privacy issues. The legality of mandating cameras also varies across local and state laws.

Abrams has her own theory as to why Uber has been slow to implement security cameras.

“Cost isn’t the issue,” she said. “It’s that it would deter drivers because a lot of drivers don’t want cameras. And so if they don’t have drivers, they don’t make money.”

Many drivers install their own dash cams to record trips, usually as backup evidence for insurance claims or to defend themselves against unfair deactivations from Uber’s platform. Uber is also piloting a new video recording feature for drivers that allows them to record video on their smartphones. But in those cases, the driver can decide what and when to record, and when to share that data.

Other demands

The survivors in the joined lawsuit also allege that Uber’s “fast and shallow background checks” are substandard and designed to make it as easy as possible for drivers to sign up quickly. Uber uses third-party companies like Checkr and Appriss to do background checks, which Sergio Avedian, senior contributor at The Rideshare Guy, says “are at best watered down and not guaranteed of bad apples from falling through the cracks.”

The lawsuit calls on Uber to also include fingerprinting, which would run prospective drivers through FBI databases.

“This is a very intentional and deliberate decision as evidenced by Uber’s active lobbying and resistance against municipalities and regulatory bodies implementing any kind of biometric fingerprinting requirements for drivers,” said Kevin Conway, managing partner at Peiffer Wolf Carr Kane Conway & Wise.

Uber has lobbied against additional background requirements for drivers, which has given the company authority to conduct its own background checks with little or no oversight, unlike most taxi operators.

Uber and Lyft say smudged fingerprints can lead to inaccurate results and that fingerprint checks reference historical arrest records, which can have discriminatory effects on some minority communities that face disproportionately high arrest rates. An Uber spokesperson told CNN arrest records are incomplete and often lack information about whether a person has been convicted of a crime.

Aside from in-vehicle surveillance and more extensive background checks, the survivors are asking Uber to implement driver training on interactions with passengers, a zero-tolerance policy for drivers, sexual harassment education and training, and a more adequate system to encourage customer reporting and monitor customer complaints.

Are Uber’s in-app safety features working?

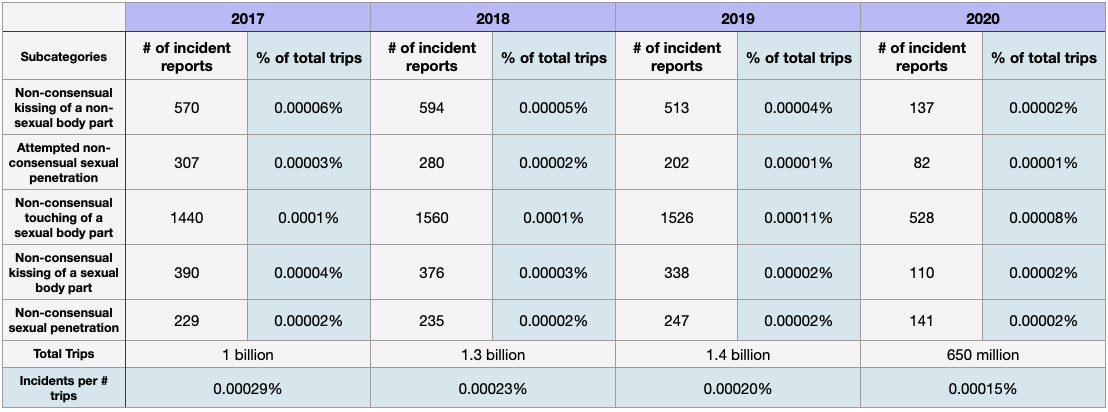

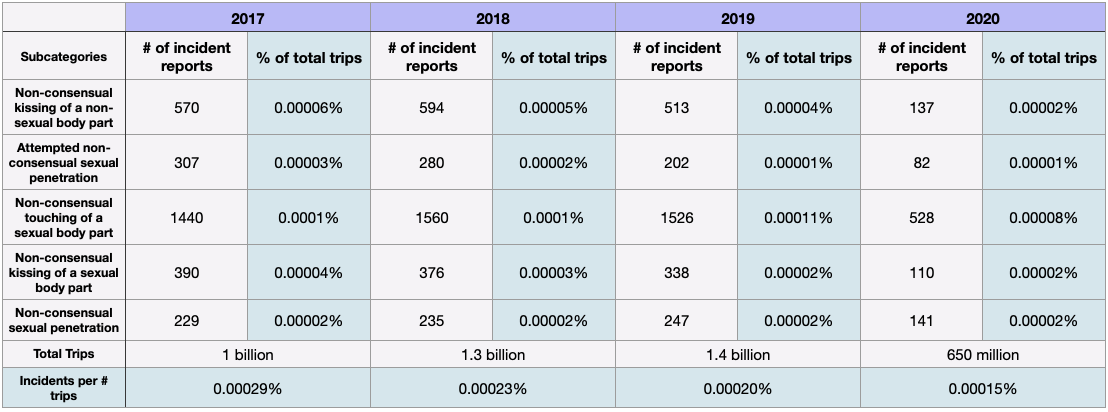

Combined data from Uber’s 2019 and 2022 safety reports, which collect instances of sexual assault reported on the app from 2017 to 2018 and 2019 to 2020.

Abrams argues that Uber’s safety features are insufficient because they’re all app-based and only potentially useful if a rider has access to their own phone.

“The majority of clients I represent and the women I’ve spoken to who have been sexually assaulted have experienced: (A) someone else ordered the ride for them; (B) their phone is dead or they can’t locate their phone to use the safety shield; or (C) if they could use their phone, they’re incapacitated,” said Abrams.

The lawyer says she has interviewed upward of 5,000 survivors over the course of several years and has seen no difference in the number of attacks before or after implementation of these in-app features.

Uber hasn’t released safety data for 2021 and 2022, and won’t say when it plans to do so. Older data backs up some of Abrams’ claims.

Uber has published two safety reports — one containing data from 2017 to 2018 and another with data from 2019 to 2020. The ride-hail company claims that the rate of sexual assault reported on the app decreased 38% between its first and second reports.

While the rate decrease is positive, not all the data delivers the same message. Over that same time period, the total number of sexual assault reports across five categories fell from 5,981 to 3,824. That drop could be explained by the decrease of trips from 1.4 billion in 2019 to 650 million in 2020.

And while the total number of incidents as a percentage of total number of rides does decrease through the years, the number of incidents in certain categories actually increases. The number of incidents increased in the categories of nonconsensual kissing, nonconsensual touching and nonconsensual penetration, or rape, between 2017 and 2019.

The total number of rape incidents also rose from 2017 to 2019. And while the number of reported rapes dropped in 2020, the rate has remained the same since 2017. In other words, there has not been an improvement in the rate of rapes on the platform.

Sexual assaults are an ongoing problem for Uber

Uber has been sued numerous times over the past few years by passengers who claim they were sexually assaulted during a ride. Lyft has faced similar lawsuits and accusations.

Under Uber’s terms of use, class action lawsuits can’t be filed against the company in cases of sexual assault, so each case has to be heard individually. This has prevented survivors from advocating for themselves collectively.

Judge Charles Breyer in the Northern District of California will preside over pretrial hearings. This will be the first time a federal judge is able to make decisions for a large amount of these cases, which will streamline the proceedings. Breyer may preside over the trials depending on whether the parties agree. If the parties do not agree to have Judge Breyer preside of the case for trial, the cases go back to their home jurisdiction for trial.

Another consolidated lawsuit has also been filed against Uber in California, but it only covers survivors in that state.

Uber has attempted, through several filings for motions to dismiss, to stop the consolidation of these cases. It argues that the company did not owe a duty to the plaintiffs to protect against criminal conduct. Lawyers representing the survivors will have to prove that Uber owed a duty of care to passengers, including the duty of taking reasonable precautions to ensure their safety.

The pretrial matters, including witness and expert depositions and document discovery, will be heard by Judge Charles Breyer. Abrams expects the timeline of the proceedings to last over the next one to two years.