Ruben Lubowski is an Adjunct Professor of International and Public Affairs at Columbia University. Speaking to Srijana Mitra Das, he discusses economic strategies underpinning environmental action:

What is the core of your research?

I’m an environmental economist. My work focuses on policies that create incentives and mobilise finance to tackle climate change, protect forests and restore natural ecosystems as part of climate solutions.

Which aspects of the economics of land-use change are becoming key as the environmental crisis grows?

It is self-evident, yet remarkable to what extent land-use decisions respond to economic incentives — when the prices of agricultural commodities increase, people plant more crops. When the prices of timber and forest products rise, people shift to planting and tending more trees. This shows there is a role for policies and incentives to move the needle in terms of the choices farmers make. The data shows us how this plays out worldwide. It’s also striking how large the reaction can be — this creates a significant opportunity for well-designed policy to make a difference.

The flipside is, policies which don’t take this into account can potentially create unintended consequences in terms of impacts on land-use patterns and nature.

Given this backdrop, which policies have successfully managed land-use change?

A recent example also gives us a powerful reason to think of land-use change as a climate solution. Just in the past year, the Brazilian government has reduced deforestation in the Amazon by over 50% — this has made Brazil a leader in reducing climate-related emissions. No other country even comes close in terms of having such a large and rapid impact. This is due to government policies, law enforcement, agricultural credit programs and carbon market-related incentives. People often think the main focus of climate action is tackling energy and the industrial sector — that is certainly key but land-use change is not a sideshow. As Brazil shows us, good land management is actually what’s working best right now.

I’ve also worked for the US Department of Agriculture — since the mid-1980s, the US has run the world’s biggest payment pro-gram for environmental services. As this is in the agricultural context, it’s not often thought of as an environmental program but the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) essentially pays farmers not to farm in areas of high environmental value. Farmers bid to participate in this and it’s mobilised over two billion dollars a year to successfully protect and restore different crop areas.

How do you evaluate international carbon emissions trading schemes today?

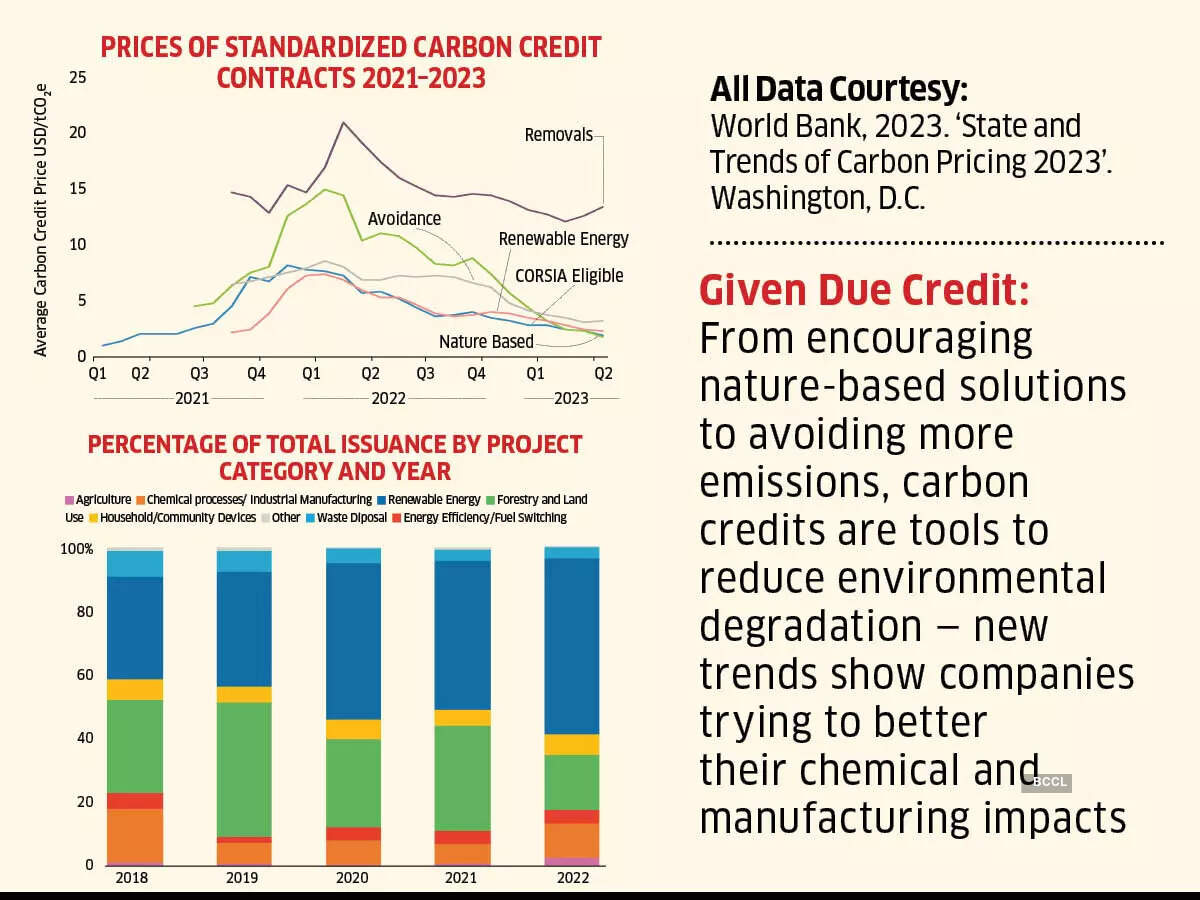

Importantly, there isn’t one single global system for carbon markets. There are two broad types — the regulated market and the voluntary market. A lot of popular attention goes to the voluntary market but in reality, this is tiny compared to the regulated or compliance markets. These are programs where governments set mandatory obligations to limit pollution and create a market for pollution permits — these markets are about a trillion dollars a year now and cover a quarter of global emissions. The voluntary markets are about two billion.

Compliance markets have been growing worldwide. Sometimes, they’ve worked in fits and starts but they have performed much better than expected at driving down emis-sions at lower costs than anticipated. This has triggered reforms, strengthening these mar-kets over time. Globally, these are growing tighter — it’s quite rare to have a regulation driven by the desire to make it stricter. Such well-designed markets are a powerful tool now for increasing global climate ambition.

There are also concerns around green-washing taking place via carbon trading schemes — how you do analyse these?

Most of those are about voluntary markets, the much smaller component where companies voluntarily pledge to take climate action. There are views that some might be justifying slower action in terms of reducing their emissions or using lower quality credits that don’t really have an impact. There are many quality challenges with carbon credits, both in terms of their supply standards or how they are generated. There has also been a lack of best practices in the kinds of claims comp-anies make when using these credits with regard to being climate-friendly, net zero, etc.

These concerns are real — and because of all this scrutiny in part, this year is see-ing several initiatives starting to address these problems. There is an effort to develop industry-wide quality standards, to govern which credits are considered good, direct investments into developing better-quality credits with new technologies and monitor-ing systems and increase attention to the claims that companies can make.

The problems are being addressed — it’s not always easy to rigorously quantify such benefits, especially with small-scale projects. But part of the solution is ultimately moving away from a piecemeal voluntary project-by-project approach and having much more standardisation, especially through govern-ment regulations and larger-scale programs which can cover sizeable regions and create bigger-scale incentives. This is a jurisdiction-al approach to carbon markets — it could be a very important environmental solution.