You may have had to read the question above twice just to confirm that you understood it correctly, so ludicrously self-evident does the answer seem.

But there was a time when this was a perfectly legitimate thing for Autocar to be asking.

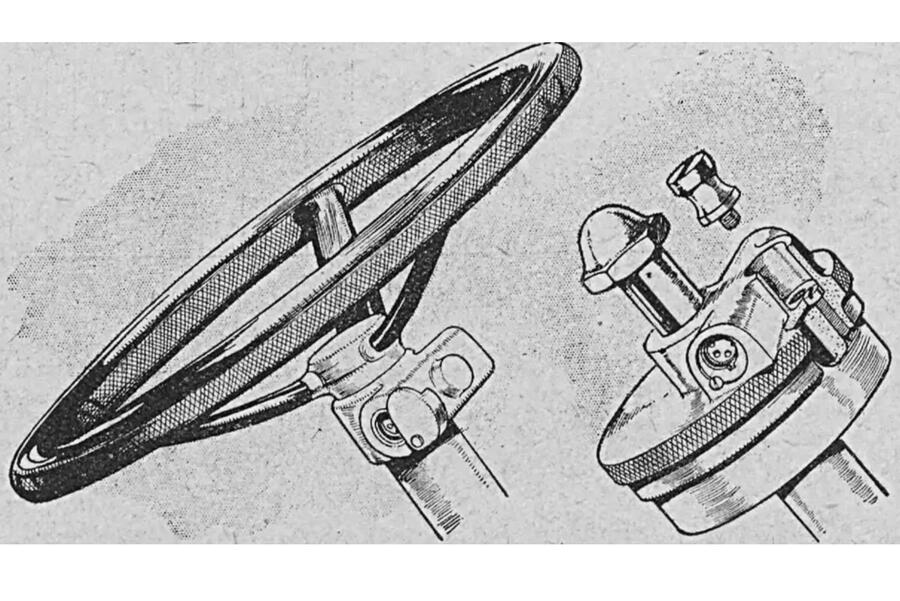

Locks for cars started appearing in late 1900s America, where “car stealing has flourished”. Initially these didn’t lock the car itself but rather the ignition, steering wheel or bonnet. In fact, one car could have as many as eight of the things.

Enjoy full access to the complete Autocar archive at the magazineshop.com

By 1921, the Daily Mail here in Britain was “calling attention to the marked increase in theft of motor cars” and imploring owners “to take the elementary precaution of having their cars fixed with one of the locking arrangements”.

Three years on, Autocar praised an “ingenious” creation: a master lock that effected every lock on a single car via cables and bolts. It’s funny to read now – as is the fuss we made about a Hillman being designed so it “can be left entirely locked up when desired”.

Of course, leaving your car unlocked left it and anything inside it vulnerable to theft. “We are often surprised at the casual manner in which people leave valuable luggage in cars without taking the trouble even to lock the doors,” Autocar once commented.

“How often, too, are cases reported of doctors losing packages of dangerous drugs from their cars?” And that wasn’t all that could happen, as Graham Greene alluded to in his ’30s novel Brighton Rock, when his unsavoury protagonist and a woman, having met in a bar, sneak out to the car park and into the back of somebody’s Lancia.

Or take the 1933 case that we reported of a man’s “engine being started and ‘revved up’ by two urchins”.