The Economic Survey 2025-26 has presented a detailed trade performance analysis of Production-Linked Incentive (PLI) sectors, positioning the automobile sector in what appears to be a favorable pattern—positive export growth accompanied by declining imports—which the Survey interprets as indicating “maturing domestic manufacturing capability.”

The Survey, released on January 28, analyzed trade data from FY21-FY25 across all 14 PLI sectors, finding significant variation in how different sectors have performed. The automobile sector’s performance is particularly notable given that exports have grown despite India facing an effective 50% tariff on goods exports to the United States, suggesting genuine competitiveness rather than favorable market access.

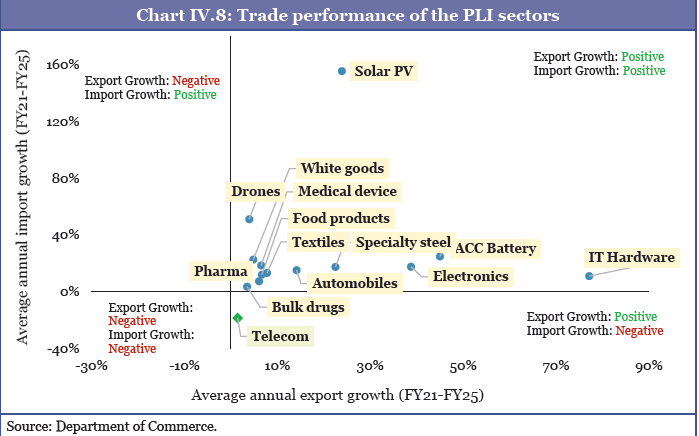

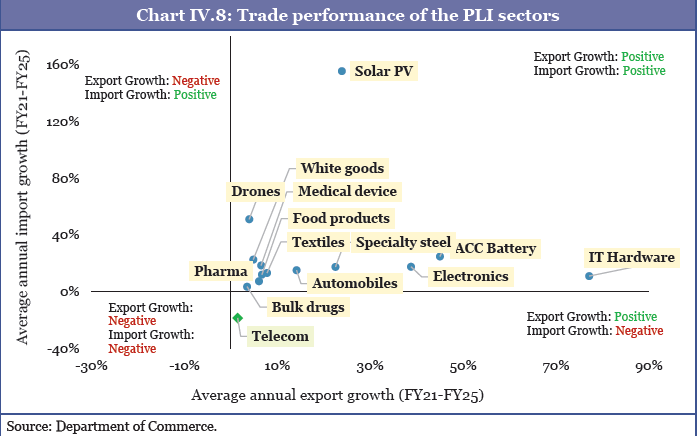

The PLI Trade Performance Matrix

The Survey presents PLI sector trade performance in a four-quadrant matrix based on export and import growth patterns. Across all PLI sectors during FY21-FY25, exports showed an average annual growth rate (AAGR) of 10.6% while imports grew at 12.6%. However, this aggregate masks considerable variation across sectors.

The automobile sector’s performance is particularly noteworthy given the challenging external environment. The Survey notes that India faces “an effective export tariff rate of 50 per cent on goods exports to the United States” due to reciprocal and penal tariffs that remain in place, yet automotive exports have sustained growth. This suggests the sector’s export performance reflects genuine competitiveness rather than favorable market access conditions.

Some sectors recorded very high export growth: IT hardware (77.2% AAGR), ACC batteries (45.0%), electronics (38.8%), solar PV (23.9%), and specialty steel (22.5%). But the critical differentiator is what happened to imports alongside this export growth.

Electronics shows 38.8% export growth but also 17.6% import growth, indicating continued dependence on imported components. Solar PV records 23.9% export growth but very high 155.4% import growth, suggesting assembly of imported components rather than deep manufacturing. ACC batteries show 45% export growth but 24.9% import growth, indicating a scaling phase with significant imported inputs. Meanwhile, white goods and drones show declining exports alongside rising imports—a pattern indicating loss of competitiveness.

The automobile sector’s position is distinct. While the Survey does not provide specific growth rates for automobiles’ exports and imports, the graphical representation positions automobiles showing modest positive export growth alongside negative import growth. The Survey groups automobiles with telecom equipment and bulk drugs in this favorable quadrant, interpreting it as evidence that “domestic manufacturing is not only maturing but is also beginning to leverage imported intermediate goods to facilitate higher-value exports” in some sectors, while others like automobiles have moved past requiring high imported intermediates.

This pattern—declining imports despite growing exports—suggests genuine import substitution is occurring. Domestic manufacturers are not just serving export markets but also replacing imported vehicles in the domestic market. The automobile sector appears to have progressed beyond the phase of requiring high imported intermediate inputs that characterizes sectors like electronics and solar PV.

The Survey’s broader analysis notes that for high-growth export sectors, “this export expansion has generally been accompanied by an increase (AAGR) in imports that has been moderate in electronics…but substantially higher in solar PV and ACC batteries.” It adds: “These trends indicate a scaling up of production capacity and the integration of value chains, suggesting that domestic manufacturing is not only maturing but is also beginning to leverage imported intermediate goods to facilitate higher-value exports.” The automobile sector’s negative import growth suggests it has moved past this integration phase into more self-sufficient manufacturing.

What This Pattern Indicates

The automobile sector’s favorable trade pattern likely reflects several factors. India’s automotive manufacturing ecosystem, which the Survey describes as “vast” and supporting “direct and indirect employment to over 30 million people,” provides depth that newer PLI sectors are still building. This established supply chain gives automotive manufacturers advantages in localizing production compared to sectors still developing their supplier networks.

The PLI-Auto scheme, approved in September 2021 with ₹25,938 crore outlay, has attracted cumulative investment of ₹35,657 crore till September 2025—exceeding the scheme’s allocation. The trade performance data suggests this investment is translating into export-oriented production that reduces import dependence rather than just scaling up assembly of imported components.

The Survey separately notes that more than 5.3 million vehicles were exported across passenger, commercial, two-wheeler, and three-wheeler segments in FY25, with “double-digit growth in the H1 of 2025-26, reflecting rising global acceptance of India-made vehicles.” This export performance across multiple vehicle categories suggests broad-based competitiveness rather than success in a narrow niche.

The export pattern shows interesting differentiation across segments and markets. In two-wheelers, Indian brands have gained significant market share in South America and Africa under their own brand names, displacing Chinese brands through superior quality and undercutting Japanese brands on price. This represents genuine brand-level international success for Indian manufacturers—not contract manufacturing for foreign brands, but competing and winning with Indian badges in overseas markets.

In passenger vehicles, the pattern is different. Indian brands have had limited success penetrating international markets under their own names, but foreign-branded vehicles manufactured in India have performed well in exports, including to demanding markets like Japan and Europe. This indicates India has achieved manufacturing competitiveness and quality standards acceptable to the world’s most sophisticated automotive markets, even if Indian passenger vehicle brands lack the international recognition that Indian two-wheeler brands are building. The distinction matters for understanding India’s competitive position: two-wheelers show brand strength internationally, passenger vehicles demonstrate world-class manufacturing capability that foreign brands leverage for their global operations.

The pattern also validates the PLI approach differently across sectors. Sectors starting from a low manufacturing base (electronics, solar PV) show high growth but continued import dependence as they build capabilities. Sectors with established capabilities (automobiles, telecom equipment, bulk drugs) show more balanced growth with genuine import substitution. Some sectors (white goods, drones) face challenges maintaining export competitiveness despite PLI support.

The Survey’s analysis suggests different PLI sectors are at different stages of development. Assembly-focused models show high import growth supporting export growth (solar PV, some electronics). Sectors with domestic value addition show declining imports with growing exports (automobiles, telecom). Component export models show moderate growth in both imports and exports (specialty steel, textiles).

Implications and Questions

The automobile sector’s current favorable position raises questions about sustainability as the industry transitions to electric vehicles and advanced technologies. The Survey separately discusses EV-related PLI schemes (ACC batteries, PM E-DRIVE) which show different trade patterns—the ACC battery sector displays high import growth alongside export growth, suggesting the EV transition may require a phase of higher import dependence before achieving current levels of localization in conventional vehicles.

While declining overall imports suggest growing localization, the Survey does not provide data on import content of exports—i.e., how much of exported vehicles’ value consists of imported components. For automotive exports, some imported content in specialized components or high-end electronics may persist even as finished vehicle imports decline. The question is whether import content is declining in proportion to import volume reduction, or whether value is being captured differently.

The Survey does not provide detailed comparison with pre-PLI trade patterns, making it difficult to isolate the PLI scheme’s specific contribution from broader industry trends. India’s automotive exports have grown over the past decade driven by factors including competitive manufacturing costs, quality improvements, and OEM strategies beyond just PLI incentives. The Survey’s data provides a snapshot but not attribution of causality.

Looking ahead, maintaining the favorable trade pattern requires continued investment in domestic supply chain capabilities, technology absorption for advanced vehicle systems, quality standards meeting international market requirements, and competitive cost structures. The Survey’s emphasis on MSMEs’ role in manufacturing—noting they account for 35.4% of manufacturing output—is relevant here, as the extensive tier-2 and tier-3 supplier network of MSMEs contributes to the ability to localize production and reduce imports.

The Survey’s projection of continued economic growth with domestic demand support and infrastructure improvement suggests a positive environment for sustained automotive performance. The upward revision of growth potential to 7% indicates capacity for absorbing additional activity without overheating. However, external headwinds including tariff uncertainties and global competition will test whether the current favorable trade pattern can be maintained.

The persistence of 50% effective tariffs on exports to the United States makes the sector’s export growth particularly significant—it demonstrates competitiveness that can overcome substantial tariff disadvantages through quality, cost structure, or market diversification. The Survey notes India’s “diversification of export destinations and import sources” as a resilience factor, which appears validated by the automotive sector’s ability to sustain export growth despite restricted access to the large US market.

For policymakers, the automobile sector’s PLI performance—growing exports with declining imports—represents a relatively successful outcome compared to other sectors. It suggests the sector is using policy support to strengthen genuine manufacturing capability rather than just assembling imported components. For the automotive industry, it signals that the investment in localization and supply chain development is yielding measurable results in trade performance.