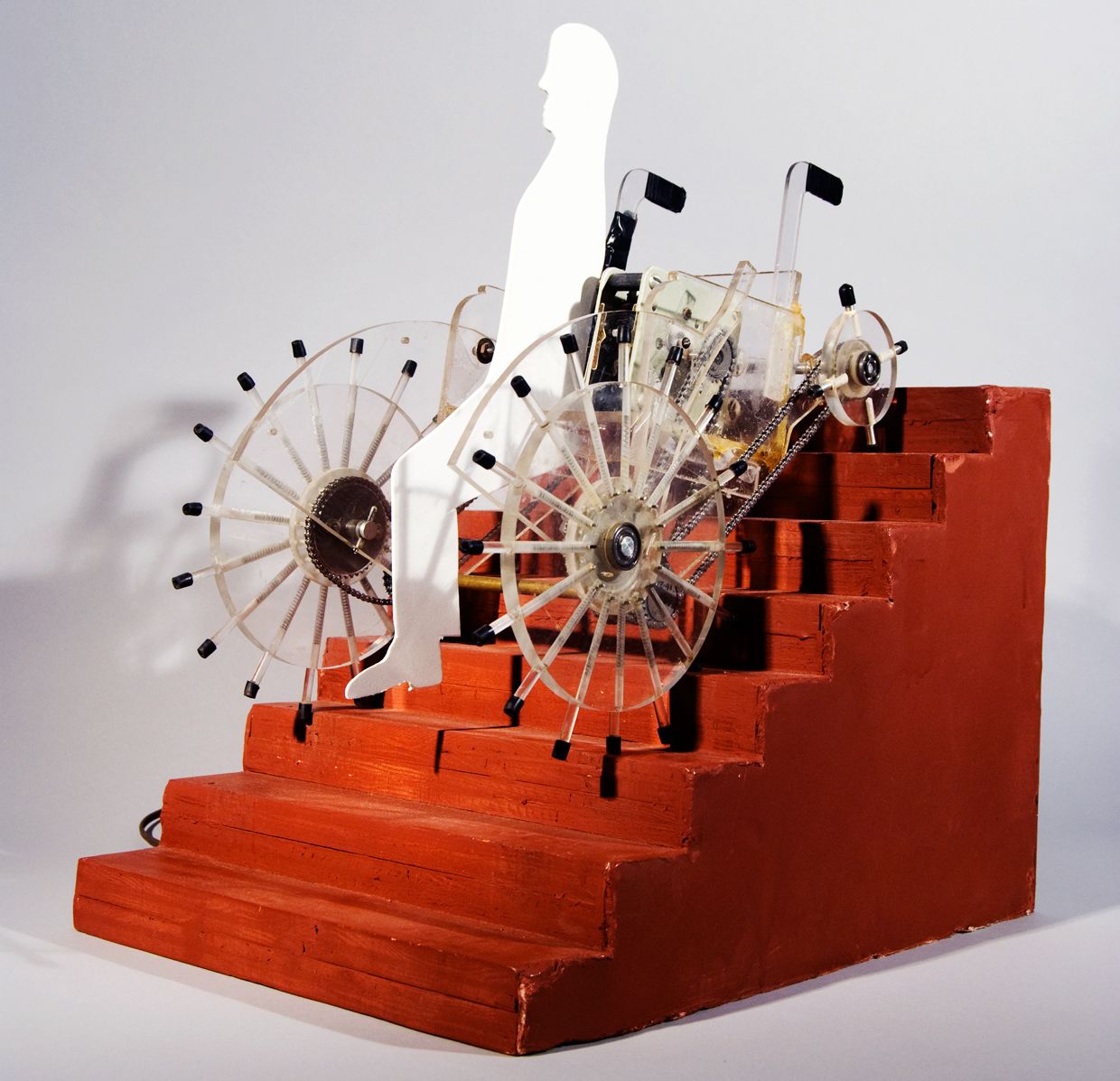

Ernesto Blanco invented his stair-climbing wheelchair in 1962 and entered it in a design challenge from the National Inventors Council, a U.S. agency that sought out technologies of potential military use. Blanco even created a one-quarter scale model [above] to show that the design actually worked. Stairs are of course tricky to navigate in any wheeled vehicle. Blanco’s design used retractable, spring-loaded, rubber-tipped spokes that came out of the rim. The chair was intended to be operated manually, but Blanco included an electric motor on his model to show how the mechanism worked [PDF]. Though he didn’t win the US $5,000 prize—in fact, the council never picked a winner—the engineer continued to work on humanitarian designs throughout his career, because he considered it an engineer’s responsibility.

Blanco’s motivation grew out of his own experiences. He was born in Cuba in 1922 and studied engineering at the University of Havana. He moved to the United States to study, receiving a degree in mechanical engineering from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, in Troy, N.Y., in 1956. He then returned to Cuba to teach engineering.

In a 2002 interview with MIT News, Blanco talked about how his Cuban background spurred his inventive spirit: “I come from a lesser-developed country. After my father died, our family knew scarcity. I started by inventing toy airplanes for myself, then an electric egg cooker. I moved on to inventing things that would help the country people, such as solar-cooled bins to store produce.”

As the political situation in Cuba became untenable, Blanco immigrated with his family to the United States in 1960. He taught at MIT for a few years, then at Tufts University for a few more. He worked with the U.S. State Department to develop cooperative engineering programs across Latin America, and he became an expert in textile machinery and started his own company.

And throughout his life, Blanco kept inventing. “Engineering is a service profession,” he said in the 2002 interview. “It is about improving things for mankind.” The stair-climbing wheelchair was his first foray into designing for the physically challenged, but it certainly was not his last. He went on to patent numerous inventions for the handicapped, especially the blind, and to design medical instruments and equipment.

Blanco returned to MIT in 1977 as an adjunct full professor, teaching engineering design. He always kept one foot in the classroom and the other in industry, and he liked to discuss the creative process of inventing with his students. Testimonials abound from those he taught. In 2011, when MIT launched a special exhibition to celebrate its 150th anniversary, the university community selected Blanco’s wheelchair as one of the 150 objects to be displayed.

To be sure, stair-climbing wheelchairs didn’t end with Blanco. Although his scale model worked, in a sense the invention was a failure. A full-size prototype was never built, nor did anyone commercialize his design. The model lived on in Blanco’s office as a conversation piece, unknown to the public at large. It took three more decades for someone to bring a stair-climbing wheelchair to market.

First came the Nagasaki Stairclimber [PDF], an electromechanical chair that was introduced in Japan in 1995. It used a track mechanism in which the outer teeth of the track pressed down on the step while a wheel moved the chair up or down along the inner surface of the track. The wheelchair grew out of local needs. Many of the steep, hilly neighborhoods of Nagasaki were inaccessible by motorized vehicles, and people grew concerned about the quality of life of the elderly. The Stairclimber, developed by researchers at Nagasaki University with assistance from Kyowakiden Industry Co., was one response.

In the end, though, only a single chair was manufactured and sold to the Nagasaki city council. The wheelchair couldn’t compete with a taxi service that dispatched two people to carry the customer up or down any hillside stairs to a waiting car. The Stairclimber was retired in 2002 due to lack of use.

Four years after the Nagasaki chair’s debut came the iBOT, created by Dean Kamen’s DEKA Research & Development Corp. and sold by Johnson & Johnson. It used a wheel-cluster mechanism with sets of wheels rotating about each other to handle stairs as well as sandy soil and uneven terrain. Although the iBOT had its fans, it was a steep investment; various models ranged in price from $22,000 to $29,000, of which Medicare would cover only about a fourth. It never sold more than a few hundred units per year and was discontinued in 2009. (The wheelchair’s balancing technology did find its way into the more popular Segway scooter.)

More recently, Toyota and DEKA announced a partnership to revive the iBOT, news that was widely cheered by the disability community. Some analysts viewed the partnership mainly as a vehicle for licensing intellectual property, but one blogger who test-drove a prototype of the new iBot in May declared that “every function has been improved,” including its stair-climbing ability. The launch date and price for the redesigned machine have yet to be announced.

Meanwhile, legislation has eased some of the obstacles for wheelchairs and their users. For example, the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 requires that all new construction in the United States comply with its extensive accessibility guidelines, resulting in a proliferation of curb cuts, ramps, and wheelchair lifts. However, historic properties, private clubs, and some religious organizations are exempt. And many countries have no comparable regulations.

And so 56 years after Blanco’s invention, there’s still a need for stair-climbing wheelchairs and plenty of room for improvement. According to a 2017 survey, nobody has yet developed the perfect chair, one that is lightweight and affordable and merges an effective mechanism with a user-friendly interface.

How would Blanco, who died last year at the age of 94, view this current state of affairs? Probably with a mixture of pragmatism and optimism. As he told his interviewer in 2002, “Inventors can’t afford to be sentimental. It’s too discouraging. We look to the future. We look to results.”

An abridged version of this article appears in the July 2018 print issue as “The Wheelchair That Might Have Been.”

Part of a continuing series looking at photographs of historical artifacts that embrace the boundless potential of technology.

About the Author

Allison Marsh is an associate professor of history at the University of South Carolina and codirector of the Ann Johnson Institute for Science, Technology & Society there.