If there was ever a company that tracked the recent downs and ups of our car industry, it’s Unipart, which was once a division of the state-owned dinosaur British Leyland but is now a thriving independent parts and logistics firm.

Neill’s worries are those of the wider industry. Tariffs would be bad, but worse would be the delays resulting from car parts held up at what’s increasingly looking like being a hard border between the UK and the Continent. That threatens to destroy the finely timed movement from supplier to manufacturer that has evolved over years of membership of the EU.

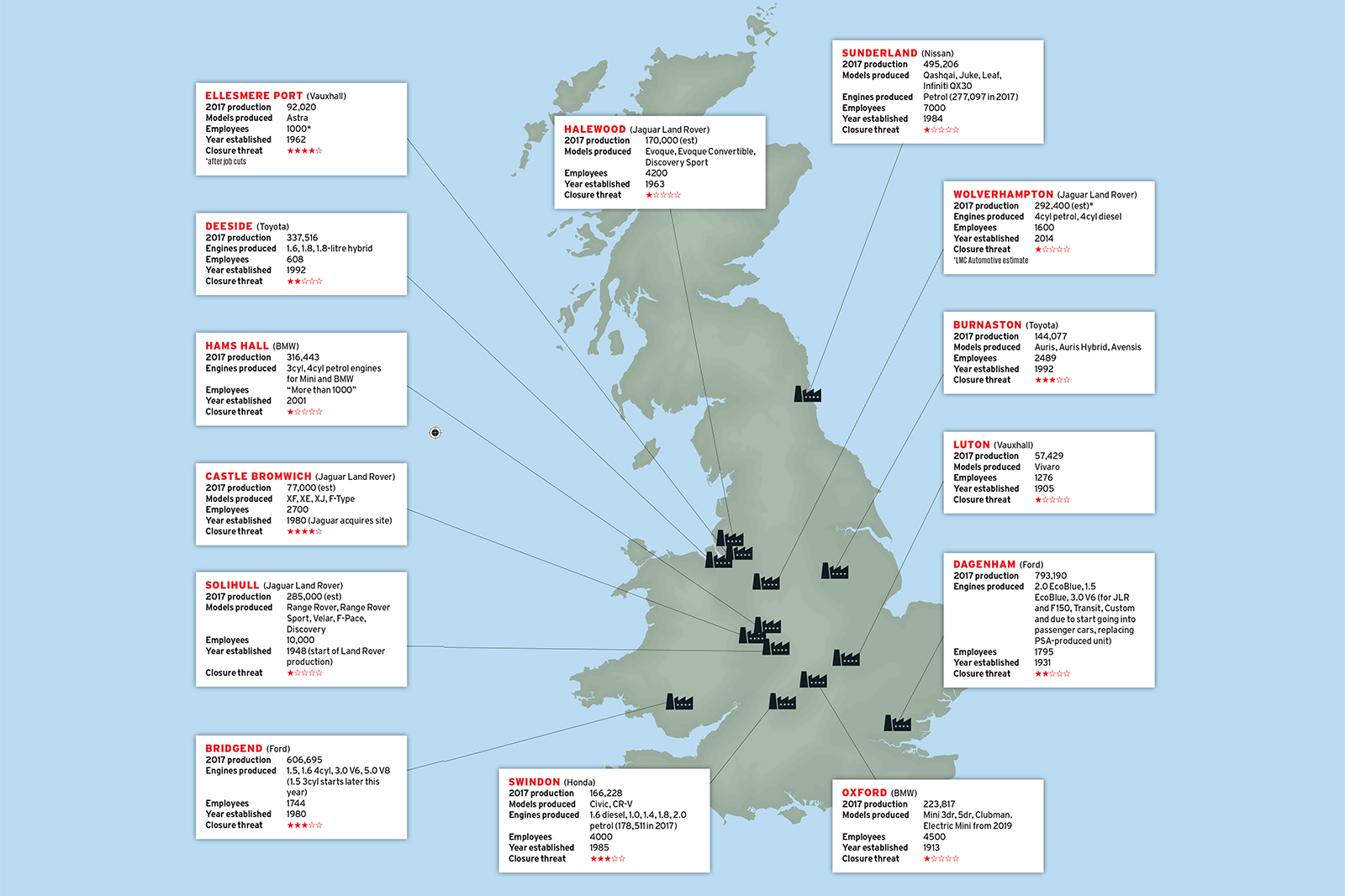

The loss of easy access to our biggest market and parts suppliers could put the brakes on a strong period of growth for British car manufacturing, argues David Bailey, professor of industry at Aston University. From a record 1.92 million vehicles made in 1972, UK car production has slumped, peaked and slumped again, but this decade it came roaring back to 1.7m vehicles (and 2.7m engines) last year, thanks in part to a resurgent Nissan and Jaguar Land Rover, our two biggest manufacturers by far. Brexit could reverse that.

BMW UK boss: We will not close UK factories post-Brexit

“There’s a real danger we’ll have another decline,” Professor Bailey said. “Production is not guaranteed to be here; it can be shifted around, and we’re in danger of a self-inflicted wound that seriously damages the automotive industry.”

Manufacturing jobs have already been lost – at Vauxhall in Ellesmere Port, at Jaguar Land Rover in Solihull and at Nissan in Sunderland. To what extent they were lost due to Brexit, the slump in diesel sales or simply cyclical market upheavals is a point that has been much debated, but the timing looks ominous.

Brexit so worries Jaguar Land Rover that its normally reticent boss, Ralf Speth, warned last month that a bad Brexit deal would cost the company more than £1.2 billion a year in lost profits and inflict serious job losses. “We want to stay in the UK… but if we don’t have the right deal, we’ll have to close plants and it will be very, very sad,” he told the Financial Times.

Jaguar Land Rover is also reeling from the diesel crisis, as are many other firms. “It’s been a huge issue for the market,” said Bailey. “Government has been all over the place on this.”

In the first six months of this year, diesel demand tumbled by 30% to the point where the fuel type accounts for just a third of sales, down from more than half at its peak from 2011 to 2014. Jaguar Land Rover sales are more than 90% diesel in the UK and the company has seen demand fall by 9% in the first six months of 2018, despite fresh product. The body that represents car makers in the UK, the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders (SMMT), has called on the Government to throw its support behind the latest cleaner diesels and help change public opinion that ‘diesel equals dirty’.

Are there any upsides for the car companies?

A hard Brexit would put barriers up and force businesses to look inward, which could boost the UK parts industry. Currently an average car built in the UK uses 44% of UK parts in terms of value. Post-Brexit, car makers might want to increase that to hit ‘rules of origin’ requirements (see below). The lack of tariffs and border hassle could make a UK part that much more competitive compared with an EU part.

For example, Aston Martin and McLaren both use Italian-made Graziano gearboxes. In the event of a hard Brexit, McLaren Automotive CEO Mike Flewitt said he would try to persuade Graziano to build a UK plant. “If the duties were there and it was harming our competitive position, absolutely we would,” he said.

McLaren currently sources 50% of its parts from the EU (outside the UK), a figure that will go down to 40% once it starts making its carbonfibre tubs in Yorkshire in 2020. That decision to shift production from Austria was made prior to Brexit, but we could see more of this. McLaren and Aston Martin have both said they’ve benefited from the fall in the pound’s value since the 2016 vote.

What do UK auto makers want from Brexit?

“We want free trade, zero tariffs, frictionless trade across borders,” Flewitt said. It’s a common refrain. Essentially, they want what we’ve got now: a customs union, free trade, common rules (and a say in how they’re made) and the freedom to hire staff from across Europe. “We need unrestricted access to the single market of Europe, our largest trading partner,” the SMMT said.

Last year, 54% of UK-built cars were shipped to customers in the EU. The SMMT reckons a no-deal shift to World Trade Organization (WTO) tariffs would add £1.8bn to the cost of exports, forcing price increases. Meanwhile, an extra £2.7bn would be paid collectively for new cars coming from the Continent.

Ford puts the blame squarely on Brexit for its loss-making second quarter in Europe this year. “The biggest issue we face is the UK,” Jim Farley, president of global markets, told investors last week. “Brexit and the continued weak sterling has been a fundamental headwind for our European business.”

So what will happen?

The latest white paper from prime minister Theresa May proposes that we stay in a version of a customs union and single market while maintaining the EU’s rules on goods such as cars. So no tariffs, no border checks and no real change, apart from making it more difficult to hire people from outside the UK.

The SMMT called it a “welcome step” that shows the Government is listening, but the hard Brexit wing of the Tory party hates it for proposing we take EU rules without having a say in how they’re made, and have forced amendments to the White Paper. There’s little evidence to suggest the EU would accept either version.

“There’s a sense of relief among auto makers that there’s a desire to stay in the single market, but they don’t know what they’ll end up with,” said Professor Bailey. “That is deterring investment in a very big way.”

What is ROO?

Rules of origin (ROO) are an essential part of a free-trade agreement made with another country to make sure a third country isn’t piggybacking the deal. If you allow a car in tariff-free from country A but 80% of parts in the car come from country C, then you’ve given away a benefit to country C for nothing in return. Trouble is, cars made in the UK are so dependent on EU parts that we would struggle to satisfy ROO when we tried to strike post-Brexit trade deals.

Key players in an £82bn industry:

Honda’s future in the UK was looking gloomy way before Brexit. It mothballed one half of its Swindon plant after sales failed to recover following the 2008 financial crisis, and then decided to produce just the Civic hatchback, dumping the Jazz and CR-V. But the new Civic is now also exported to the US for the first time, and production numbers rose 24% last year. It still makes a diesel in the attached engine plant but has been able to swing production more towards petrol. Swindon’s future probably hinges more on whether US president Donald Trump’s threatened tariffs come to pass. That plus a hard Brexit could sink its UK manufacturing. “We struggle to see a bright future for Honda in Europe,” auto analyst Max Warburton wrote for Bernstein Research earlier this year.

The UK’s single largest car factory, Nissan in Sunderland, is regarded as a bellwether for Brexit because of its size; nearly half a million vehicles were built there last year, of which 80% are exported. In April, Reuters reported Sunderland would shed “hundreds” of jobs after demand slumped. Nissan’s UK sales were down 30% in the first half of this year, but that’s mostly due to ageing product. Expect production numbers to climb again after the Juke and Qashqai are replaced and it gains the X-Trail SUV. No start dates for those cars have been given.

Luton and Ellesmere Port looked vulnerable to closure after the brand’s sale to cost-cutting PSA Group coincided with Brexit uncertainty. However, PSA came to Luton’s rescue with news that the factory would make a new range of vans on PSA platforms. PSA boss Carlos Tavares said no decision would be made on Ellesmere Port until 2020, closer to the time when the current Astra is replaced. A third of its workforce was cut at the beginning of this year in an attempt to increase its cost-competitiveness. If that works and we have a deal on Brexit that mirrors current benefits, it could yet survive.

Future of Vauxhall’s Luton plant secured

The union Unite gave an indication of the paranoia among manufacturing workers in the UK over the upheaval surrounding diesel engines when it called for Ford’s two vast engine plants, the petrol-focused Bridgend and diesel-making Dagenham, to switch to making electric powertrains instead. Ford is too pragmatic for that, but its big problem is losing JLR as a client for the V6 petrol and V8 in Bridgend, and the V6 diesel in Dagenham by 2020. The V6 diesel has a new life in the F-150 pick-up in the US, but production at Bridgend will fall by some 150,000 engines. A new range of 1.5-litre engines in both plants will give them a boost, but most head to Ford’s assembly plants in Europe, so any Brexit-derived disruption will hurt.

BMW is unlikely to leave Mini’s ancestral home in Cowley (it’s due to add the electric Mini from next year) but has other options in the case of a hard Brexit. The firm ramped up Mini production at its Dutch contract manufacturing plant to 170,000 units in 2017 and has increased the head count there, Reuters reported in June. The company has been vocal on the threats of Brexit, particularly in terms of customs hold-ups, but its engine plant at Hams Hall is well positioned to ride out the diesel slump: it doesn’t make any.

“Let’s be clear, Toyota, Nissan and Honda came here to access the European single market, which is why they’ve got a particular problem with Brexit,” says Aston University’s Professor Bailey. Toyota’s 2500 employees in Derbyshire breathed a sigh of relief when the firm announced the next Auris for the plant starting early next year. It should boost production after a lean couple of years, but the Avensis has now gone and won’t be replaced. Toyota’s engine plant in Deeside in North Wales, meanwhile, has thrived thanks to the interest in Toyota hybrids amid the diesel slump.

Jaguar Land Rover Britain’s biggest auto maker made just over half a million cars in the UK last year, but 2018 has brought problems. First it said it was cutting production at Halewood, then in April it announced the loss of up 1000 agency jobs at its biggest plant in Solihull. To make up the shortfall, JLR shifted over 362 full-time staff from Castle Bromwich, where it builds Jaguars suffering some of the biggest sales declines this year. JLR has blamed the diesel slump and model cycles, but its global strategy is also a cause. Production is growing in China and it’s just about to start production of the Discovery in Slovakia. After being saved from closure when Tata took over JLR in 2008, Castle Bromwich now looks vulnerable.

The luxury brands Bentley, Rolls-Royce, Aston Martin and McLaren might grumble about Brexit, but they have no real choice but to ride it out; too much of their global brand allure is tied up in the ‘Made in Britain’ promise.

To McLaren’s Mike Flewitt, it’s just another challenge to negotiate. “In one market, Singapore, I have a 180% tariff. We’re talking maybe WTO tariffs at 10%,” he said. “I’m not even convinced there will be tariffs.”

Tariffs are fourth on the list of Brexit fears for Aston Martin CEO Andy Palmer. “That’s least of my concerns,” he says. Number one for him is border drag, two is rules of origin and three is hiring the right people. “We’re employing people from the likes of Ferrari, and I need to be able to say to them they’re going to be able to stay after Brexit,” he said.

Nick Gibbs

Read more

Brexit: Bentley could shift production to Europe in ‘worst case scenario’

BMW UK boss: We will not close UK factories post-Brexit

Brexit: EU single market is ‘critical’ to UK automotive sector