Audi’s self-driving unit has tapped a startup with a unique approach to lidar as it ramps up testing in Munich using a fleet of autonomous electric e-tron crossover vehicles.

Audi subsidiary Autonomous Intelligent Driving, or AID, said Wednesday it’s using lidar sensors developed by Aeva, a startup founded just two years ago by veterans of Apple and Nikon.

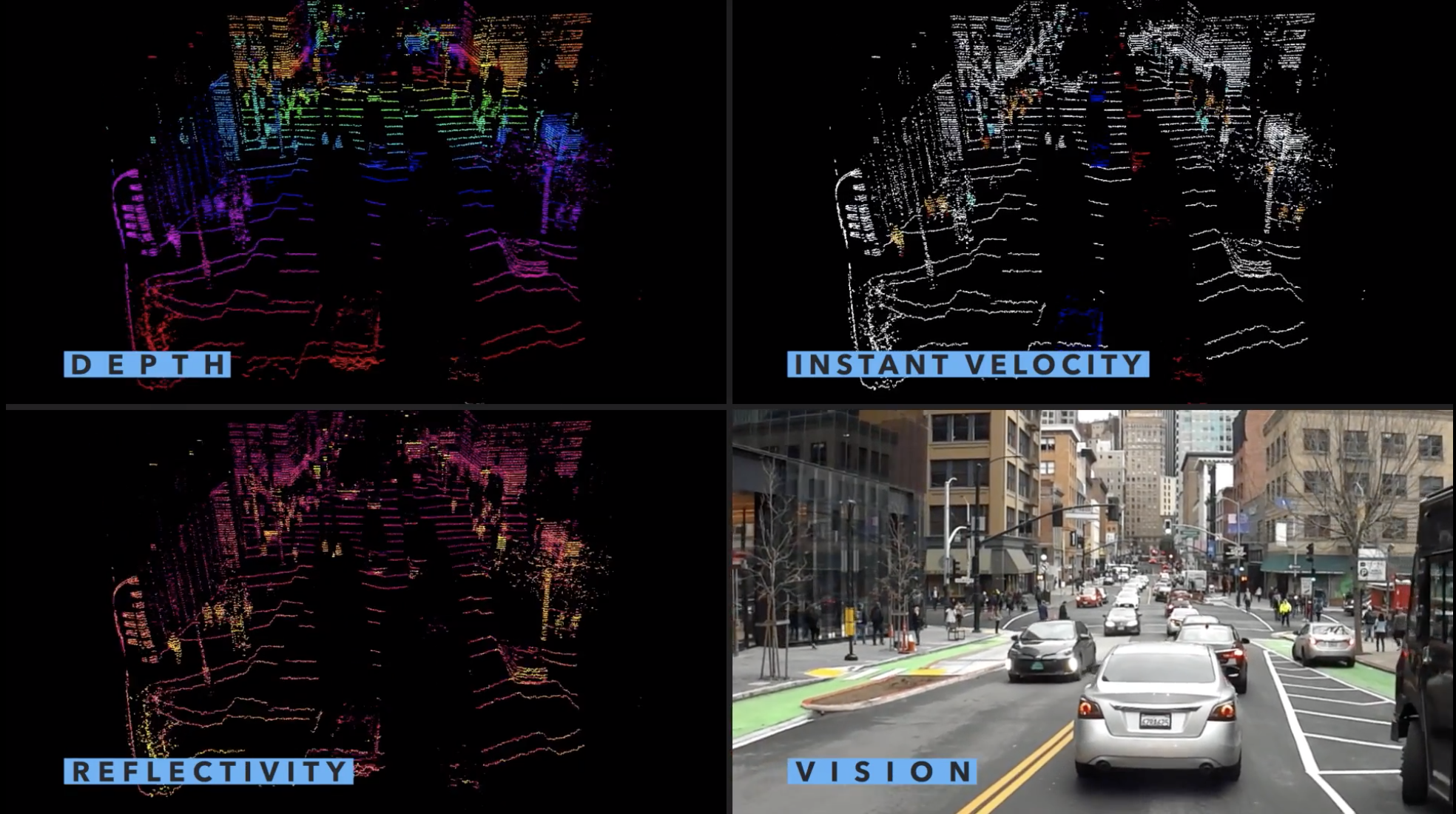

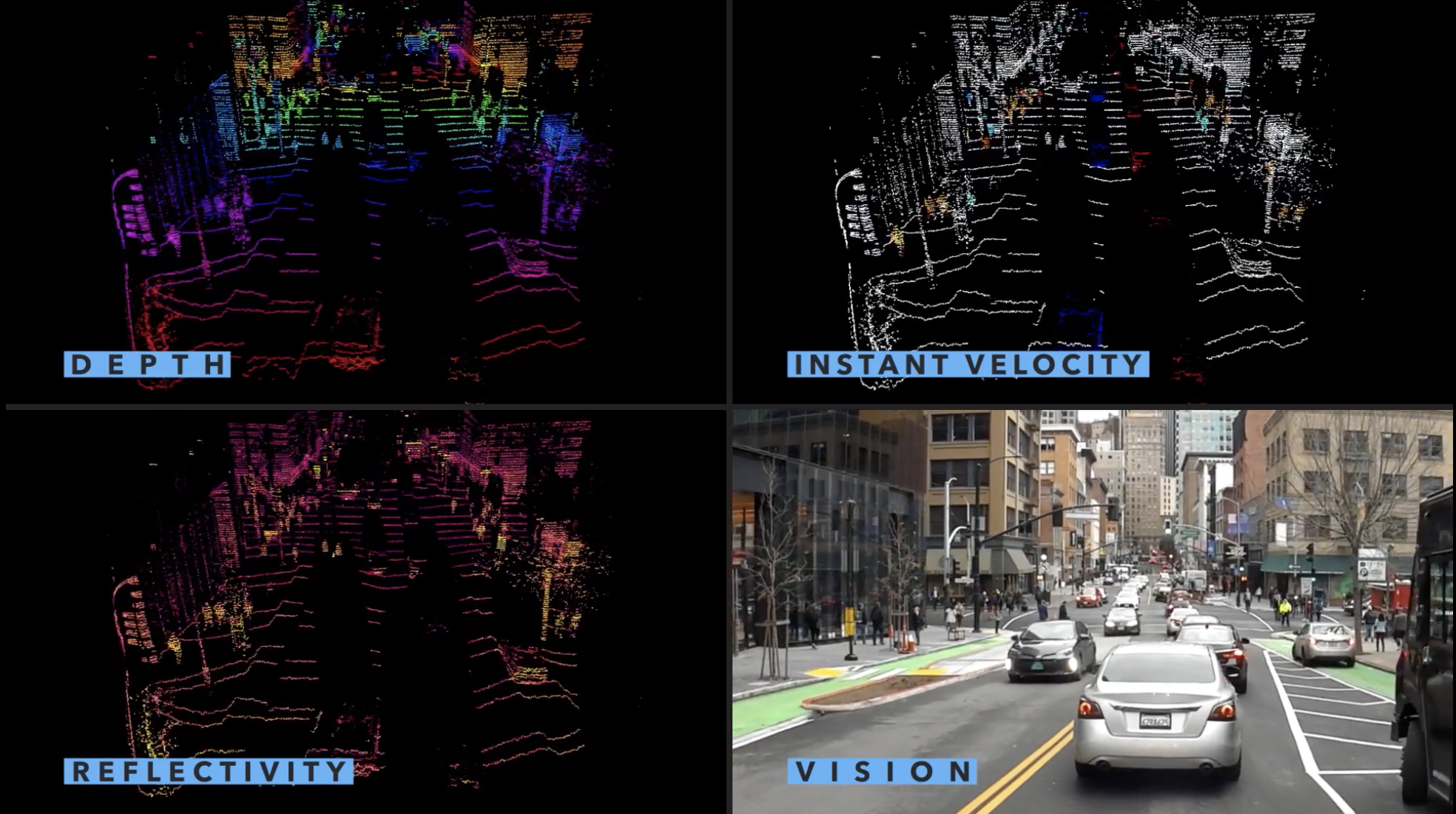

Aeva, a Mountain View, Calif.-based company started by Soroush Salehian and Mina Rezk, has developed what it describes as “4D lidar” that can measure distance as well as instant velocity without losing range, all while preventing interference from the sun or other sensors. Move past the 4D branding-speak, and the tech is compelling.

Lidar, or light detection and ranging radar, measures distance. It’s considered by many (with Tesla as one exception) in the emerging automated driving industry as a critical and necessary sensor. And for years, that industry has been dominated by Velodyne.

Today, there are dozens of lidar startups that have popped up with promises of technological breakthroughs that will offer lower-cost sensors with better resolution and accuracy than Velodyne. It’s a promise that is fraught with challenges, notably the ability to scale up manufacturing.

Traditional lidar sensors are able to determine distance by sending out high-power pulses of light outside the visible spectrum and then tracking how long it takes for each of those pulses to return. As they come back, the direction of, and distance to, whatever those pulses hit are recorded as a point and eventually forms a 3D map.

Aeva’s sensors emit a continuous low-power laser, which allows them to sense instant velocity of every point in the frame at ranges up to 300 meters, the company says. In other words, Aeva’s sensors can determine distance and direction, as well as speed of the objects coming to or moving away from them.

This is a handy perception feature for autonomous vehicles operating in an environment of objects that travel at different speeds, like pedestrians, bicycles and vehicles.

Aeva, backed by investors including Lux Capital and Canaan Partners, says its sensors are also unique because they’re “free” from interference from other sensors or sunlight.

It was this combination of long-range perception, instantaneous velocity measurements at cm/s precision and robustness to interferences that sold AID CTO Alexandre Haag on the Aeva sensors.

Aeva spent the past 18 months going through a validation process with Audi and parent company Volkswagen. This announcement confirms that Aeva has made it past a critical hurdle in Audi’s AV plans. Aeva’s sensors are already on Audi e-tron development vehicles in Munich. The automaker plans to bring autonomous driving to urban mobility services within the next few years.

Interference is possible and can cause a stream of random points on a 3D map if the lidar is pointed directly at the sun or if there are multiple sensors on the same vehicle. Lidar companies have instituted various techniques to prevent interference patterns; autonomous vehicle developers also account for potential interference problems from the sun and snow by creating algorithms to reject these kinds of outliers.

Still, Salehian argues that interference is a significant challenge.

When you talk about the challenge of building to scale and designing for mass scale, it’s not just about how easily they can be manufactured, Salehian contends. “It’s also about having these things work in unison together on a row. So when you’re talking about hundreds of thousands of these cars, that’s a big deal.”