The “goodwill repair” saga for Tesla has yet another chapter. After we told you the story of Sergio Rodriguez’s Model X, which had a bizarre manufacturing issue with its windshield, Steve Lehto read our article. He commented on it in the video above. Lehto is a Lemon Law attorney with 28 years of experience, and he has interesting insights to give. His main one is that Tesla could not evade responsibility by simply changing the way it calls repairs in their invoices from “warranty” to “goodwill,” as the company has done in Rodriguez’s case.

We have tried to contact him on January 23 but still have not heard back from him. When we do, he’ll probably be able to clarify some doubts we had when we watched his video.

We are more familiar with the Romano-Germanic Law system than with common law. Anyway, what a law establishes is not necessarily what a judge will rule in the first legal system. It is not rare to have conflicting decisions and no technical explanation for them.

Although this is an entirely different discussion, it is relevant to our point. Romano-Germanic Law professors try to call Law as science, but what defines science is repeatable and reproducible experiences, and that is not always the case. Perhaps that also applies to common law, but Lehto will know more about it than we could. The point is that we may never know for sure how a legal battle will end.

With proper introductions made to the subject, here’s something Lehto said that intrigued us:

“I guarantee you that they cannot evade the Lemon Law by simply mislabeling repair orders.”

If Tesla cannot do that, why has it achieved precisely this in a case the attorney Edward C. Chen reported to us? If you have not read the article, an arbitrator recognized software updates 2019.16.1 or 2019.16.2 caused problems regarding range and supercharging speed to the respective car owner. Anyway, a lemon law buyback was not granted because the arbitrator said Tesla was not “given the requisite number of repair attempts.” Chen alleges it did.

This shows that law application in the US probably also depends very much on the people judging the cause. If things were so sure, attorneys or judges would not be necessary. Anyone with a problem would ask the companies for what the law establishes, and things would be immediately settled. Sadly, that’s not the case.

We understand Lehto means there is a high probability that he could make the Lemon Law prevail regardless of goodwill or warranty fixes as long as they could be named “repairs.” Anyway, we have the impression he did not notice exactly what happened in Rodriguez’s case.

The Model X owner took his car to the Palm Springs Tesla Service Center, and this is what happened in his own words:

“Initially, when they checked the windshield, it was classified as ‘basic vehicle warranty.’”

This is the document Rodriguez received that states what the windshield problem was.

We have written an article that shows what causes the issue. According to Chad Hrencecin, from “The Electrified Garage,” and George Catalin Marinescu, from “Doctor Tesla,” this happens due to a wrong assembly procedure. In other words, it is something that the warranty should cover.

Yet, when Rodriguez took his car back, this is what he noticed:

“The final invoice was changed to ‘goodwill.’ I noticed that and spoke to a few other owners.”

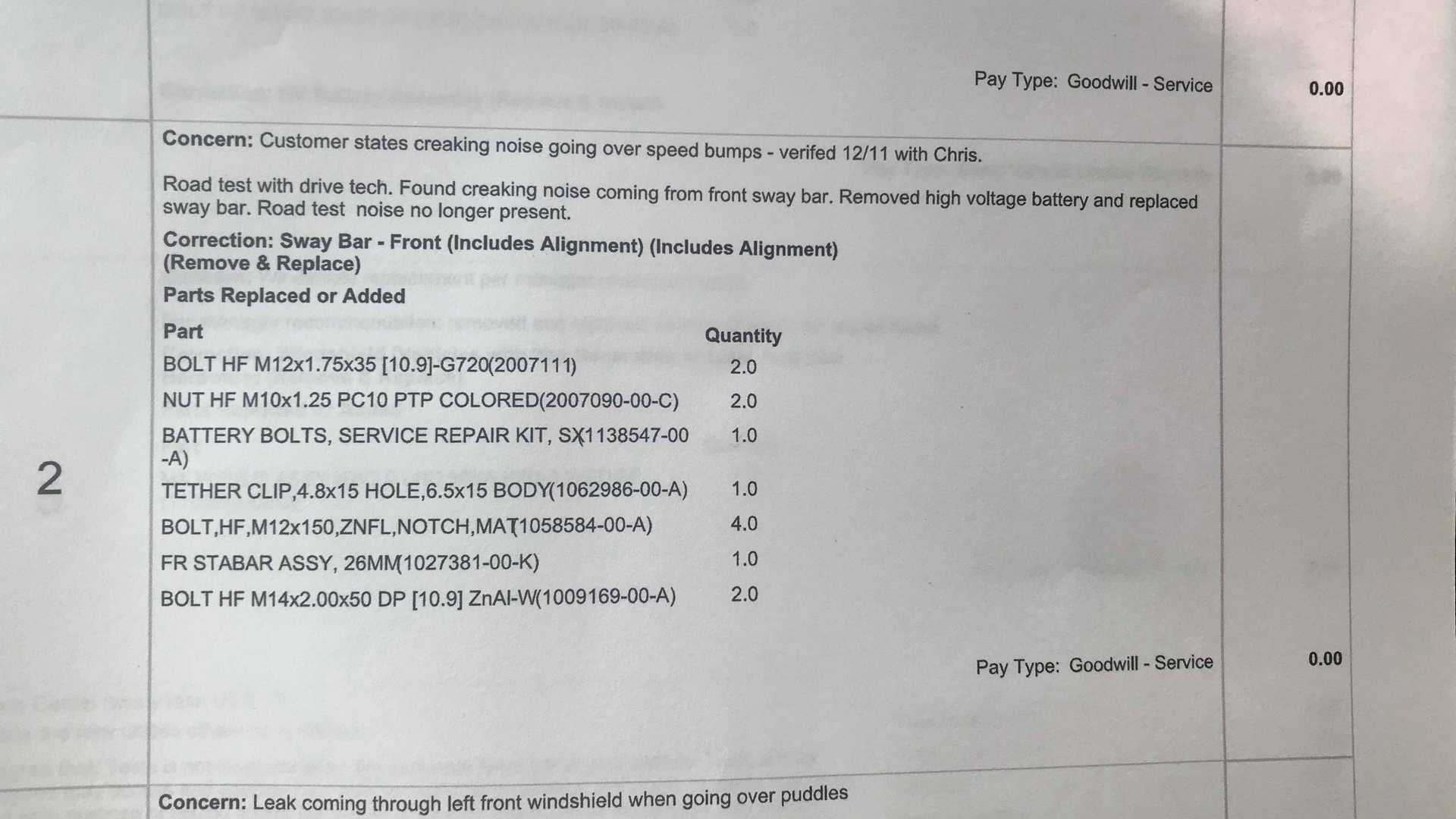

You can see the document the Model X owner talks about below.

Rodriguez also had that impression. This is what he had to say about the video:

“As an attorney, I would expect you to know that laws may vary by State. You also made a comment as to Tesla seeing my driving through puddles as abuse. The video I posted does not show a massive puddle. You pretty much are suggesting that I shouldn’t drive my vehicle when it rains. That preposterous. Any reasonable vehicle owner should have an expectation that water shouldn’t enter the vehicle while driving (unless they are reckless and drive into a lake or some other body of water with depth). Going through a puddle and having water splash onto my dashboard is clearly a manufacturing defect. Tesla replacing my windshield as ‘goodwill’ wasn’t optional. Having Tesla tell me my buyback request was denied because out of 50 days in service only 23 were for warranty repair is the problem.”

That is what led us to ask why Tesla did that. And why it still does that quite frequently, by the way. Lehto insisted in the video that this is not an escape from the Lemon Law. To prove his point, he partially reads the MCL Section 257.1402:

“If a new motor vehicle has any defect or condition that impairs the use or value of the new motor vehicle… the manufacturer or a new motor vehicle… shall repair the defect or condition as required under section 3. Doesn’t say under warranty. Doesn’t say as goodwill. It just says they shall repair it.”

Indeed. But check the full text from the law here. The bolds are on us.

If a new motor vehicle has any defect or condition that impairs the use or value of the new motor vehicle to the consumer or which prevents the new motor vehicle from conforming to the manufacturer’s express warranty, the manufacturer or a new motor vehicle dealer of that type of motor vehicle shall repair the defect or condition as required under section 3 if the consumer initially reported the defect or condition to the manufacturer or the new motor vehicle dealer within 1 of the following time periods, whichever is earlier:

(a) During the term the manufacturer’s express warranty is in effect.

(b) Not later than 1 year from the date of delivery of the new motor vehicle to the original consumer.

The law does not mention that the manufacturer has to list the service as a warranty repair, but it makes sure that these repairs have to be reported while the “express warranty is in effect.” The problem also has to prevent “the new motor vehicle from conforming to the manufacturer’s express warranty.”

If it doesn’t, these vehicles will probably not be covered by the Lemon Law. Check what goodwill repairs are, according to the attorney.

“Goodwill repairs by definition are the repairs that a manufacturer does or authorizes to pay even though they weren’t legally required to do so.”

Sorry for being repetitive, but, if goodwill repairs are the ones a manufacturer is not obliged to do, warranty repairs probably are the ones that prevent “the new motor vehicle from conforming to the manufacturer’s express warranty.”

Lehto may be able to prove that this is not the case in courts, but this seems to be a pretty logical reason for naming warranty repairs as goodwill. In a legal battle, it looks like a big headstart. We will wait for the attorney’s analysis on this.

Anyway, Lehto said he thought of a couple of other reasons for that which were not mentioned in our article. He gives only this one.

“They might have not actually considered that a warranty repair. They might have said: ‘That’s actually customer misuse.’”

The attorney gives a more emphatic conclusion to that.

“I think it’s most likely the fact that the repair the man was complaining about was an unusual one he admitted happened because of the way he was driving in certain conditions and they may have looked at it and said: ‘You know something? This guy did this to the car. We’ll fix it but we’re doing it under goodwill.”

Nobody searches for puddles to hit with any car. Regardless, that eventually happens. When it happens, water is not supposed to enter the cabin. If it enters, especially in a brand-new vehicle that never had any crash, that is a manufacturing problem. Not an unusual one in Teslas, as Hrencecin and Marinescu told us.

What, then, would be Tesla’s motivation for that? Lehto’s video gives us his hunch.

“The point is they called it a goodwill repair. Why would they do that? Probably because they are trying to blame him… If I had to guess, that’s what it is. ‘But Steve, you are guessing.’ Yes, I’m guessing but I have been practicing law for 28 years exclusively in the field of consumer protection in Michigan doing nothing but lemon law claims.”

It is a pity Lehto does not present a legal reason for Tesla to want to blame its customers in these situations. It would not do so just for PR reasons. In other words, only to look good for whichever audience it wants to please.

There is obviously a legal reason for Tesla to avoid naming them as such. Lehto is more inclined to support the one Chen also believes to be stronger: preventing technical service bulletins (TSB’s), recalls, and NHTSA.

“I believe that it’s possibly because they are concerned about TSPs and NHTSA reportings. But even that I don’t think that will get them around it.”

Can the windshield urethane leak be considered a safety problem? Recalls necessarily involve the protection of the passengers. We will talk to more owners that had this warranty/goodwill change and try to determine if Tesla did that only in problems related to safety or not. In case you are among them, you are welcome to get in touch.

The sad part of the video is that, although Tesla may not be trying to evade the Lemon Law, it would still be trying to blame customers for something it knows that is not their fault. If Lehto is right in his guessing, evidently.

We can’t help wondering: How could Sergio Rodriguez have prevented his windshield from being correctly glued in place? Is Graham Stephan responsible for the lack of paint he found in his Model 3? Why didn’t Tesla ask David Rasmussen if he wanted the update that crippled his Model S’ battery?

The truth is that the EV manufacturer does not look better under any angle in this story. Again, if the company is trying to blame its clients for defects it is responsible for, for whatever reason, it is harming the very people that helped it become a $100 billion enterprise. Is it for a greater good? A few casualties to win a war? One day we may see the very people that think that way – the ones that call these customers FUDsters – in their shoes. Call that justice.