Beijing: China buys more electric vehicles than any other country, and most sales occur in big cities such as Beijing and Shanghai. EV buyers there can afford to spend 300,000 yuan ($43,000) on a sedan like the Tesla Model 3.

Fang Yunzhou, chairman of one of Tesla Inc.’s local rivals, has a different customer in mind: a consumer who lives in a less affluent small city or even a farmer in the countryside. “Our goal is to provide a real product affordable for the whole market, rather than a rich kid’s toy,” he says.

Fang, 45, is the founder of Hozon New Energy Automobile Co., a 6-year-old EV maker backed by local governments in eastern China’s Zhejiang province and one of a handful of companies that want to expand the market for EVs. Hozon is betting there’s a path to profitability in selling inexpensive battery-powered autos in China’s flyover territory. The price of Hozon’s first SUV, the Nezha N01, starts at less than 67,000 yuan. In early July the company began delivery of another SUV, starting at about 140,000 yuan, that can travel more than 250 miles on a single charge.

Targeting drivers outside big cities could help Hozon survive the massive consolidation taking place in China’s EV industry. As auto sales boomed in the mid-2010s, hundreds of EV makers hoped to become the country’s answer to Elon Musk’s Tesla. But demand started to falter even before the effects of Covid-19 hit the economy, because there was a reduction in government incentives in mid-2019. Only 11 of the country’s EV makers succeeded in raising funds last year, among them WM Motor Technology Group, Li Auto, and Hozon, according to advisory company Automobility Ltd. Adding to the pressure, in January, Tesla began delivering EVs from its new Shanghai plant.

The coronavirus pandemic is making the situation even worse. Sales of new-energy vehicles dropped more than 37% in the first six months of 2020 after falling sharply in the second half of 2019.

Chinese President Xi Jinping’s government is trying to boost the industry by helping automakers sell in areas they’ve usually overlooked. In July, Beijing announced an initiative involving 10 companies, including Hozon, to promote EV sales in villages, towns, and small cities with subsidies and other incentives such as preferential loans.

At a time when China’s relations with the U.S. and other countries are deteriorating, EV makers including Hozon are part of a broader push by Xi to build Chinese alternatives to Western companies. “We must ensure key and core technologies are in our own hands and aspire to build strong domestic automobile brands,” Xi said on July 23 while touring a facility of state-owned FAW Group, another automaker that’s targeting prospective rural buyers.

Source: Bloomberg

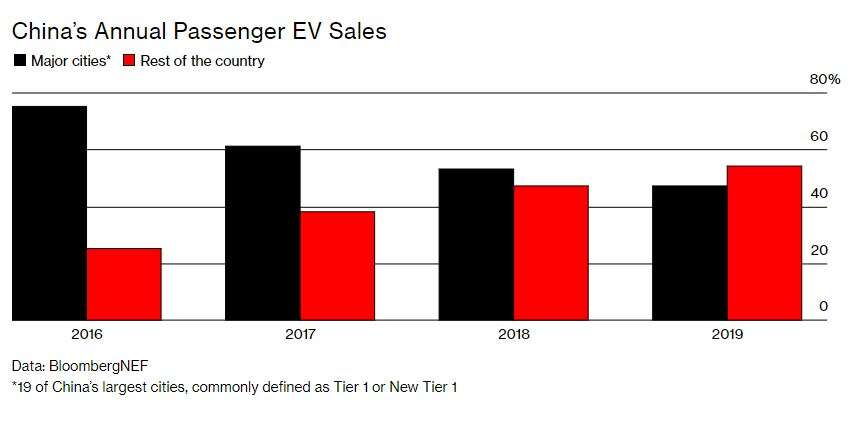

More than 500 million people live in China’s rural areas. Although their incomes generally are lower than those of city dwellers, some have cash to spend, according to China EV100, a think tank that focuses on EV development. In the countryside, residents own fewer than 150 cars per 1,000 people, about half that of residents in China’s biggest cities, according to BloombergNEF. “There’s a huge market for such vehicles in the rural market,” says Xu Haidong, deputy chief engineer of the China Association of Automobile Manufacturers, a trade organization that’s helping organize campaigns to encourage promoting electric-vehicle sales.

There are advantages to owning an EV in the countryside. Because most rural Chinese live in a house rather than a high-rise, an EV owner can simply plug the car into an ordinary outlet and doesn’t need the charging infrastructure more common in big city apartment buildings. With the company offering a subsidy of as much as 7,000 yuan for buyers, a consumer can purchase an EV with as little as 18,000 yuan down—and farmers with a good credit history are eligible to drive away without any initial payment.

Even with this marketing push, challenges remain. Hozon, like the rest of its direct EV competitors, needs more capital. “This industry by nature requires huge investment in product development and manufacturing,” says Charley Xu, managing director and partner at Boston Consulting Group in Shanghai.

Fang is moving ahead with a $428 million fundraising round announced on July 20, to be followed by an initial public offering, possibly in 2021. Rivals including NIO Inc. and Xpeng Motors already have had IPOs or big-name corporate investors such as Alibaba Group Holding Ltd. enabling them to more effectively compete against foreign automakers expanding into the market.

Li Auto Inc. filed on July 24 for a Nasdaq listing to raise as much as $950 million, and WM Motor is considering a Shanghai IPO. Moreover, there’s a limit to how far automakers can go with low-margin sales in less affluent parts of China, says Jing Yang, director for corporate research with Fitch Ratings in Shanghai. “This is a short-term remedy for the market weakness and for domestic brand EV makers to clear some inventory,” she says. “They still have to work on the higher end. That’s the ultimate trend for the development of EVs.”

Fang argues that there’s space in the market for an EV maker selling less expensive cars. All the attention within China on Tesla has helped educate consumers about the potential of EVs, he says. “There’s such a huge population in China, and even if Tesla could sell 1 million cars a year here,” Fang says, “that would still be only 1 million.”

Also Read: Plug it in: Electric car charging station numbers are rising