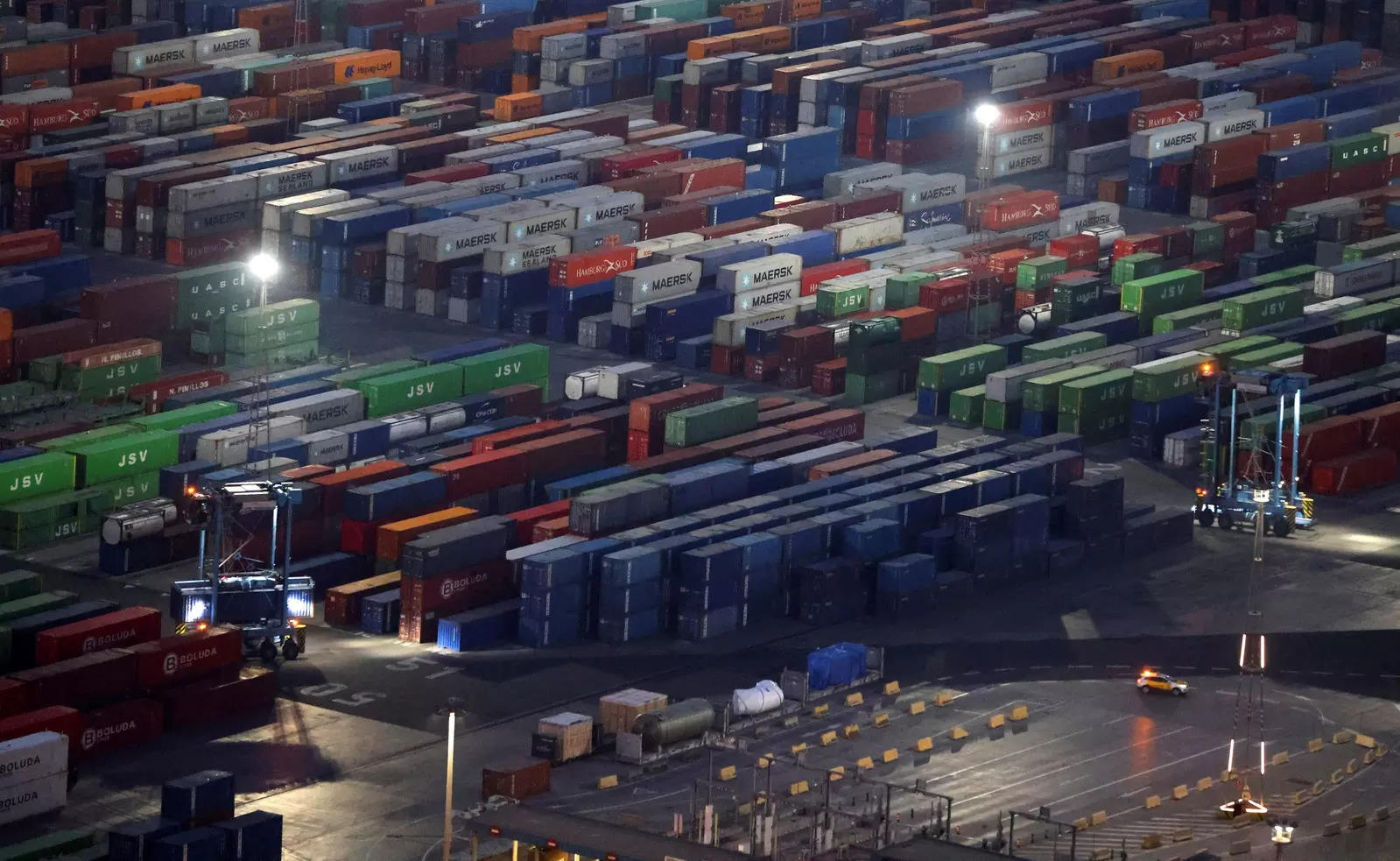

Lianyungang: Towering cranes work overtime swinging containers from cargo vessels in the eastern Chinese port of Lianyungang, racing to keep ahead of a perfect storm unleashed by the pandemic that has created gridlock in global shipping.

As the huge containers were flung onto trucks with a thunderous clang, Shi Jiangang, a top official with Chinese shipping company Bondex Logistics, reflected on the backlog.

“It’s been a very great challenge,” he said.

The ship being offloaded was a South Korean vessel that normally also carries passengers but has been given over entirely to cargo. In the distance, a fleet of other vessels waited offshore.

Lianyungang is not alone.

The global shipping network that keeps food, energy and consumer goods circulating — and the world economy afloat — is facing its biggest stress test in memory.

Maritime trade came under the microscope after a Japanese-owned megaship ran aground in the Suez Canal, blocking the busy channel for nearly a week.

It was refloated last week but the larger crisis remains, amid warnings that soaring freight costs could affect supplies of key goods or consumer prices.

The situation arose last year as the expanding pandemic jammed the sprawling, predictable patterns by which shipping containers are shared around the world’s ports.

When many countries began easing Covid-19 restrictions late last summer, a wave of pent-up demand from hunkered-down consumers bingeing on internet purchases delivered a shock to supply lines.

Exports from nations like China soared.

But since the end of 2020, vessels have piled up outside overburdened Western ports, leaving Asian exporters clamouring for the return of empty containers needed for further shipments.

At Lianyungang — China’s 10th-busiest port, according to the World Shipping Council — desperate firms are pressing rail-cargo containers into maritime service, placing rush orders for new ones, and rerouting some shipping to other Chinese ports.

The price to ship a 40-foot container from Lianyungang to the United States has soared to more than $10,000, from the usual $2,000-$3,000, Shi said.

The situation is “putting pressure on everyone in the supply chain”, he said.

American consumer demand has been a key driver.

The Port of Los Angeles said last month that processed volume in February jumped 47 percent year-on-year, the strongest February in its 114-year history. The number of empty containers stranded there has also soared.

An LA port official told AFP last week that more than two dozen ships were waiting to berth outside Los Angeles and Long Beach, the two busiest ports in the United States.

Normally there is no wait, but delays now average more than a week.

“We basically have a couple of weeks of work, but more ships come in every day,” another West Coast port official told AFP.

Compounding the gridlock, many container vessels had been pulled from the market for re-fitting to meet carbon-reduction standards, while social distancing and occasional coronavirus clusters among dockworkers have also slowed processing.

Port of Los Angeles Executive Director Gene Seroka said recently the facility was focused on vaccinating port workers and pushing cargo through.

“It’s critical that we clear the backlog of cargo and return more certainty to the Pacific trade,” Seroka said.

Commodities information provider S&P Global Platts said vessels were also logjammed in Singapore, the world’s busiest container transshipment port, and that sailing-schedule reliability was at a 10-year low.

Not everyone is complaining, though.

Denmark’s Maersk, the world’s largest container transporter, swung from a loss in 2019 to a $2.9 billion profit last year largely thanks to soaring volumes and higher prices in 2020’s final quarter.

But concerns are growing.

German Industry Federation director Holger Losch said in a statement that the situation was beginning to hit German industry.

“Sectors that are dependent on delivery of raw materials or components, as well as the shipping of their finished products… suffer from this in particular,” Losch said.

Meanwhile, smaller export-reliant countries from Southeast Asia to Latin America served by lower priority feeder routes are struggling to get their goods to market.

The one-two punch of the pandemic and the Suez Canal backlog has sparked a conversation about necessary shipping industry reforms, particularly the need for greater digitisation to smooth flows and help respond to crises.

Current arrangements “have proven to be increasingly clumsy… and equally ineffective and costly to cope with demand shifts,” Vincent Clerc, Maersk’s CEO of ocean and logistics said recently.

The longer-term impact on trade and consumers remains difficult to forecast as no one knows for sure when the situation will ease, or if it might worsen.

Jon Gold, a vice president of supply chains at the US National Retail Federation, said backlogs are expected to spread to the US east coast, due partly to the Suez blockage.

So far, big US retailers have largely absorbed added freight costs, but consumers are expected to feel the pinch at some point, he said.

Estimates range widely from a few more weeks of backlog to several more months.

“Who knows what happens when you get out of a pandemic?” Maersk CEO Soren Schou said at a recent conference.

“I don’t think any of us that are alive have tried (that) situation.”