The Covid pandemic has ravaged lives & livelihoods across India. The periodic lockdowns since March of 2020 have taken a toll on several sectors. The promising signs of economic recovery after the first wave ran into a brutal second wave and a fresh round of curbs. As a result, there have been a raft of downgrades in growth estimates.

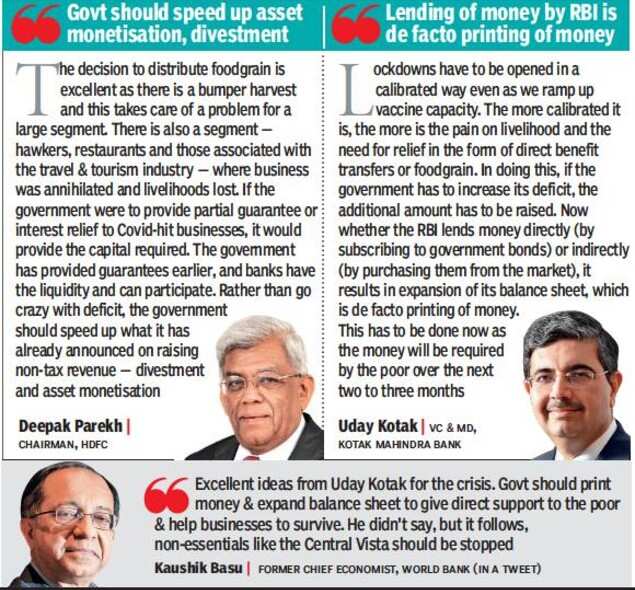

Against this backdrop, there have been calls from sections of India Inc for a large fiscal stimulus, including printing money, to nurse the economy back to health and help sectors flattened by the virus. TOI spoke to a cross-section of experts — former central bank governors, bankers and economists — to get a sense of whether printing money is needed to get the growth engines roaring again.

While there are concerns over an adverse impact on India’s sovereign ratings, given the severe hit across sectors, it may be time to set aside those fears for the moment and focus on taking every possible step to put the economy back on track, at the earliest…

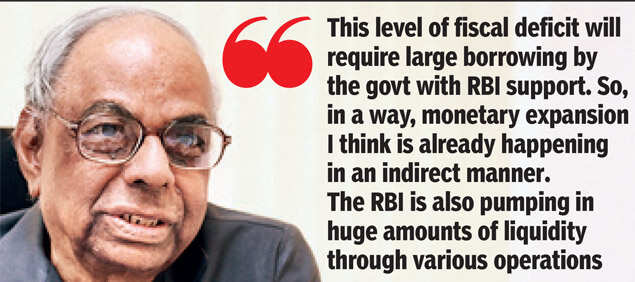

Monetary expansion already happening

– By C Rangarajan

There is no doubt that government expenditure has to remain high. The actual stimulus is a consequence of the level of deficit that is being maintained. The Budget indicates a deficit of 6.8% for the Centre. The states will have another 4%. So, the Centre and states’ combined deficit will be around 10.8% of the GDP. The expenditure as a result of the Covid pandemic will see the Centre’s deficit exceed 6.8% and it could be 7-8% of the GDP.

The government has assumed a nominal income of 14.4% for 2021-22. Given the lockdown, it will be around 13.4% — 1 percentage point less. The gross tax revenue that has been assumed is unlikely to be met. Non-tax revenues will also be low despite the dividend from the RBI. So, the fiscal deficit of the Centre will be 7-8% of the GDP.

This level of fiscal deficit will require large borrowing by the government with the support of the RBI. So, in a way, monetary expansion I think is already happening in an indirect manner. The RBI is also pumping in huge amounts of liquidity through various operations. Expenditure is being supported by the borrowing with the help of the central bank. The RBI will have to watch out for the impact of liquidity on prices.

The expenditure of the government will need to be expanded to increase healthcare infrastructure. It will also need to be for vaccination. The Centre has provided Rs 35,000 crore in the Budget for vaccination and that figure will need to be doubled and, third, if lockdowns extend beyond June, funds may be needed to support vulnerable groups and the poor. Besides, there will be expenditures to stimulate specific sectors. All of this could be something in the range of Rs 2 lakh crore, or 1% of the GDP. This could call for some amount of adjustment of other expenditures. Vulnerable groups can be supported by way of some cash transfer through appropriate mechanisms.

The writer was governor of the RBI (As told to Surojit Gupta)

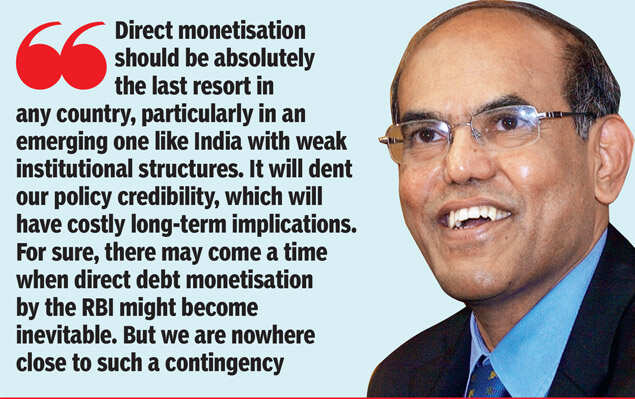

Direct monetisation should be last resort

– By D Subbarao

The current situation does not call for the RBI directly monetising the deficit. The cost of doing that will be much more than the benefits. There is an enormous amount of liquidity in the system. Banks are flush with funds and will be too happy to finance the government. In the unlikely event of liquidity pressures building up, the RBI can always resort to open market operations (OMOs).

The question of the RBI directly monetising the deficit arises if private credit demand picks up and yields spike sharply. We are nowhere near such a situation. Direct monetisation of the deficit is not necessary, not desirable, not called for. Even with indirect support through OMOs, the RBI has to be less aggressive than last year because of inflation concerns.

Given the extremely limited fiscal space, the government should first try to reprioritise expenditure within the overall budgeted ceiling. Last year the safety-net of MNREGA worked very well. This time too, the government should enlarge MNREGA although it may be less effective than last year because the pandemic has spread to rural areas and labour may be apprehensive about coming in for manual work. If the MNREGA option does not work out, the government will have to enlarge the free foodgrain scheme. Direct cash transfers should be the last resort.

Any spending by the government is demand-stimulating. The first preference should be to spend on investment — on capital expenditure already planned — as this will generate jobs and incomes and create productive assets. If the health situation, God forbid, becomes so bad that works cannot be implemented, direct consumption support will be inevitable.

When people talk about monetisation, they neglect to appreciate two things. First, direct monetisation does not mean the RBI giving money free to the government. The RBI will charge interest, but if you work through the dynamics of the combined balance sheet of the government and the RBI, it will turn out that the government gets money at a subsidised interest rate. That subsidy comes from the banks as they lose their business of lending to the government. You do not want to cripple banks at a time when they are already struggling. The second thing people don’t realise is that it is not just direct monetisation that will involve the RBI printing money. Even regular OMOs mean printing money.

Given the fiscal pressures, there is very little wriggle room for the government. If direct transfers become absolutely inevitable, then some reallocation from capital to current expenditure will become necessary. Additional borrowing should be the last resort. In the hierarchy of contingency planning, I would say spend on capital expenditure and spend on MNREGA. If because of the pandemic in rural areas, there is no demand for MNREGA, then resort to enlarged free foodgrain supply and direct cash transfers. If you then run short of money because of revenue shortfall, resort to additional borrowing.

Direct monetisation should be absolutely the last resort in any country, particularly in an emerging one like India with weak institutional structures. It will dent our policy credibility, which will have costly longterm implications. For sure, there may come a time when direct debt monetisation by the RBI might become inevitable. But we are nowhere close to such a contingency.

The writer was governor of the RBI (As told to Mayur Shetty)