India’s foreign exchange stock has touched $600 billion – the fourth highest in the world, ahead of Russia. That heap of dollars gives us macroeconomic stability. We now have enough to pay for 18 months of imports, whereas back in the crisis year of 1991 we didn’t have enough forex for two weeks.

At the very least we need foreign exchange to pay for importing crude oil, the lifeline of transport and logistics. We are also import-dependent for a variety of items, including vaccine supplies, steel and auto components. Is there a downside to having a large war chest of dollars? It’s complicated, but yes, there are downsides. First, some good news though.

Sign of sound economy

Unlike all the major, dollar hoarding central banks – China, Russia, Saudi Arabia and Japan – we are not an export surplus country. Much of their pile is the accumulation from years of earning more dollars than they spend. For us, it is the opposite. We may be the only large Asian country with a current account deficit, i.e., we import much more than we export, and still have large foreign exchange reserves. That is creditable.

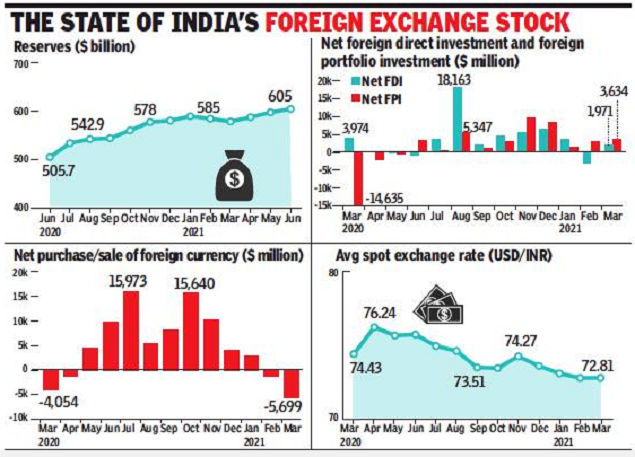

If every year we fall short of dollars, how come our forex stock keeps rising? The reason is the current account deficit is offset by a large influx of capital flows. Dollars flow into India through foreign portfolio investors (FPI) or as a foreign direct investment (FDI). This inflow from the purchase of assets like shares shows the confidence of foreign investors in India’s growth prospects.

In the past three decades, India has attracted nearly $500 billion as FDI. Beyond FPI and FDI inflows into the stock market are loans. These are called external commercial borrowings. The total outstanding foreign loans are $560 billion, or about 93% of our foreign exchange reserves. That’s a downside.

Fickle friends

The stock market inflows, especially FPI, can easily and abruptly make an about-turn. Such investors can be fickle, or nervous, or simply riskaverse, and will pull out funds at the drop of a hat, although pulling out FDI is not that easy. Similarly, Indian companies having large dollar obligations of short- and long-term loans are also a warning sign. We need enough dollars to at least pay off the short-term debts.

Even NRIs can withdraw large dollar deposits suddenly. That’s what they did in 1990 when there was panic before the first Iraq war. Also, if India’s rating drops below investment grade, no foreign lender would be willing to refinance our old loans. Our coffers will become empty repaying loans. That’s why India’s large forex stock, to the extent it has fickle flows, should not make us complacent. Unless our exports exceed imports, we will remain vulnerable.

Idle money rocks the rupee

The second downside to a large dollar pile is that it earns very little interest. If it represents a national asset, is there a better use for it? Third, large foreign holdings in India’s stock market make its value vulnerable to ebbs and flows of forex. Indeed, the rupee usually gets stronger on days when the stock market rises, and vice versa. Is it healthy that the purchasing power of our importers is dependent on fickle foreign investors?

‘Free money’ addiction

The fourth downside is that a large forex pile means RBI’s balance sheet gets bloated. Since the balance sheet is measured in rupees, it expands whenever the rupee weakens. This is “free” gain to RBI, which it can then pass on as dividends to the Centre. A very large balance sheet size means even a slight weakening translates into “notional” gains of thousands of crores, or profit for RBI.

When currency fluctuates, the gains and losses should normally not be encashed. But large revaluation gains on rupee weakening could become a continuing source of fiscal financing for a central government in desperate need. This can lead to fiscal “addiction” or even dilution of RBI’s independence.

Look beyond US dollar

The dollar is not our currency. Too much of it can become a headache. Unlike rupee debt we cannot forgive our dollar debt. Countries like Russia, despite having large foreign reserves, are moving away from the dollar. There are geopolitical tensions with the US, and Russia doesn’t want to depend on New York clearing banks (dollar transactions can only be cleared by US banks). India should also look to diversify its forex holding away from the dollar, and examine the optimal size of foreign reserves for our needs.