When the U.S. invaded Afghanistan in 2001, the global economy looked a lot different: Tesla Inc. wasn’t a company, the iPhone didn’t exist and artificial intelligence was best known as a Steven Spielberg film.

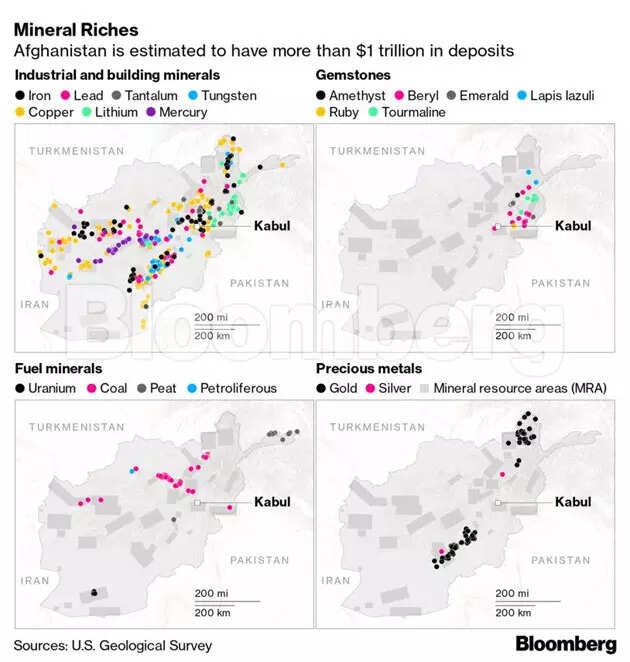

Now all three are at the cutting edge of a modern economy driven by advancements in high-tech chips and large-capacity batteries that are made with a range of minerals, including rare earths. And Afghanistan is sitting on deposits estimated to be worth $1 trillion or more, including what may be the world’s largest lithium reserves — if anyone can get them out of the ground.

Four decades of war — first with the Soviet Union, then between warring tribes, then with the U.S. — prevented that from happening. That’s not expected to change anytime soon, with the Taliban already showing signs they want to reimpose a theocracy that turns back the clock on women’s rights and other basic freedoms rather than lead Afghanistan to a prosperous future.

But there’s also an optimistic outlook, now being pushed by Beijing, that goes like this: The Taliban form an “inclusive” government with warlords of competing ethnic groups, allows a minimal level of basic human rights for women and minorities, and fights terrorist elements that want to strike the U.S., China, India or any other country.

“With the U.S. withdrawal, Beijing can offer what Kabul needs most: political impartiality and economic investment,” Zhou Bo, who was a senior colonel in the People’s Liberation Army from 2003 to 2020, wrote in an op-ed in the New York Times over the weekend. “Afghanistan in turn has what China most prizes: opportunities in infrastructure and industry building — areas in which China’s capabilities are arguably unmatched — and access to $1 trillion in untapped mineral deposits.”

For that scenario to have even a remote possibility, much depends on what happens the next few weeks. Although the U.S. is racing to evacuate thousands of Americans and vulnerable Afghans after a rushed troop withdrawal ending 20 years of war, President Joe Biden still has the power to isolate any new Taliban-led government on the world stage and stop most companies from doing business in the country.

In a statement on Tuesday, the Group of Seven nations said the legitimacy of any Afghan government hinges on its adherance to international obligations including ensuring human rights for women and minorities. “We will judge the Afghan parties by their actions, not words,” the group said after a virtual leaders meeting.

The U.S. maintains sanctions on the Taliban as an entity, and it can veto any moves by China and Russia to ease United Nations Security Council restrictions on the militant group. Washington has already frozen nearly $9.5 billion in Afghanistan’s reserves and the International Monetary Fund has cut off financing for Afghanistan, including nearly $500 million that was scheduled to be disbursed around when the Taliban took control.

To have any hope of accessing those funds, it will be crucial for the Taliban to facilitate a smooth evacuation of foreigners and vulnerable Afghans, negotiate with warlords to prevent another civil war and halt a range of human-rights abuses. Already tensions are growing over an Aug. 31 deadline for troops to withdraw, with the Taliban warning the U.S. not to cross what it called a “red line.”

Still, the Taliban have several reasons to exercise restraint. Kabul faces a growing economic crisis, with prices of staples like flour and oil surging, pharmacies running short on drugs and ATMs depleted of cash. The militant group this week appointed a new central bank chief to address those problems, just as his exiled predecessor warned of shocks that could lead to a weaker currency, faster inflation and capital controls.

‘Nothing Is Unchanged Forever’

The Taliban also want sanctions lifted, with spokesman Suhail Shahee telling China’s state-owned broadcaster CGTN this week that financial penalties would hurt efforts to rebuild the economy. “The push for more sanctions will be a biased decision,” he said. “It will be against the will of the people of Afghanistan.”

Leaders of the militant group have said they want good international relations, particularly with China. Officials and state-run media in Beijing have softened the ground for closer ties, with the Communist Party-backed Global Times reporting that Chinese investment is likely to be “widely accepted” in Afghanistan. Another report argued the “the U.S. is in no position to meddle with any potential cooperation between China and Afghanistan, including on rare earths.”

“Some people stress their distrust for the Afghan Taliban — we want to say that nothing is unchanged forever,” Hua Chunying, a Chinese Foreign Ministry spokeswoman, said last week. “We need to see the past and present. We need to listen to words and watch actions.”

For China, Afghanistan holds economic and strategic value. Leaders in Beijing have repeatedly called on the Taliban to prevent terrorists from plotting attacks against China, and view strong economic ties as key to ensuring stability. They also see an opportunity to invest in the country’s mineral sector, which can then be transported back on Chinese-financed infrastructure that includes about $60 billion of projects in neighboring Pakistan.

U.S. officials estimated in 2010 that Afghanistan had $1 trillion of unexplored mineral deposits, and the Afghan government has said they’re worth three times as much. They include vast reserves of lithium, rare earths and copper — materials critical to the global green-energy transition. But flimsy infrastructure in the landlocked country, along with poor security, have hampered efforts to mine and profit off the reserves.

The Taliban takeover comes at a critical time for the battery-materials supply chain: Producers are looking to invest in more upstream assets to secure lithium supply ahead of what Macquarie has called a “perpetual deficit.” The U.S., Japan and Europe have been seeking to cut their dependence on China for rare earths, which are used in items such as permanent magnets, though the moves are expected to take years and require millions of dollars of government support.

One major problem for the Taliban is a lack of skilled policy makers, according to Nematullah Bizhan, a former economic adviser to the finance ministry.

“In the past they appointed unqualified people into key specialized positions, such as the finance ministry and central bank,” said Bizhan, now a lecturer in public policy at the Australian National University. “If they do the same, that will have negative implications for the economy and for growth in Afghanistan.”

Officially, Afghanistan’s economy has seen rapid growth in recent years as billions in aid flooded the country. But that expansion has fluctuated with donor assistance, showing “how artificial and thus unsustainable the growth has been,” according to a recent report from the U.S. Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction.

China has been burned before. In the mid-2000s, investors led by state-owned Metallurgical Corp. of China Ltd. won an almost $3 billion bid to mine copper at Mes Aynak, near Kabul. It still hasn’t seen any output due to a series of delays ranging from security concerns to the discovery of historical artifacts, and there’s still no rail or power plant. MCC said in its 2020 annual report it was negotiating with the Afghan government about the mining contract after earlier saying it was economically unviable.

The Taliban are trying to show the world it has changed from its oppressive rule in the 1990s, saying it welcomes foreign investment from all countries and won’t allow terrorists to use Afghanistan as a base. Janan Mosazai, a former Afghan ambassador to both Pakistan and China who joined the private sector in 2018, sees “tremendous opportunities for the Afghan economy to take off” if the Taliban prove they’re serious about “walking the talk.”

But not many are optimistic. Reports have emerged of targeted killings, a massacre of ethnic minorities, violent suppression of protests and Taliban soldiers demanding to marry local women.

“Everyone’s just in crisis mode,” said Sarah Wahedi, a 26-year-old tech entrepreneur from Afghanistan who recently fled the country. “I don’t see the entrepreneurs getting back to business unless there’s a huge overhaul in the Taliban’s behavior. And there’s nothing I’ve seen that makes me think that’s going to happen.”