/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/70511577/VRG_ILLO_5017_D_Novgordoff_Cobalt_Mining.0.jpg)

Andre clocks into his job at the Kamoto Copper Company (KCC) in the Democratic Republic of Congo at 7 in the morning, and he leaves at 6 at night. The work is physically demanding, and while KCC provides Andre with lunch, he says the food quality is poor, and he’s often hungry afterward. He is also thirsty, with only a little over a liter of water provided to him a day, despite toiling deep underground in an open-pit mine that gets swelteringly hot.

“We asked KCC for more water, but they haven’t done anything,” Andre, whose real name is being withheld to protect his identity, said in an interview with human rights watchdog group Rights and Accountability in Development (RAID), a transcript of which was shared with The Verge. “I am often thirsty, but I have to endure.”

KCC is the largest cobalt-producing mine in the world. Located in the heart of the DRC’s Katangan Copperbelt, each year, the mine churns out over 20,000 tons of the silvery metal used in cell phone, laptop, and electric car batteries. Largely owned and operated by multinational mining company Glencore, KCC prides itself on supporting the local economy and upholding high labor standards. In 2020, Reuters reported that Tesla inked a deal with Glencore to purchase a quarter of the mine’s cobalt for its EV batteries, a move seen as an attempt to insulate it from allegations of human rights abuses in its supply chain.

The DRC produces roughly 70 percent of the world’s cobalt supply. For years, human rights watchdogs have been raising the alarm about dangerous working conditions and the use of child labor in the artisanal mining sector, where informal workers (workers not employed by a company) mine cobalt by hand using their own resources.

Historically, large, industrial, company-run cobalt mines like KCC have received less scrutiny. But working conditions there are far from ideal, according to interviews with nearly a dozen current KCC employees and contractors conducted by RAID and The Verge. The employees, all of whom requested anonymity due to concerns over company retaliation, described working long hours with limited food and water for pay that often does not cover living expenses. That’s especially true for workers employed through subcontractors, who make up 44 percent of KCC’s 11,000-strong workforce.

Jean, a KCC security guard employed by a subcontractor, earns just $135 a month working 50 hours a week. Another contracted security guard, Marc, makes $300 a month working 66 hours a week. For an average household of four adults and two children, a living wage in the region is $402 per month, according to RAID.

“The food is not sufficient. This salary is nothing. There is no promotion at our company,” Marc tells The Verge.

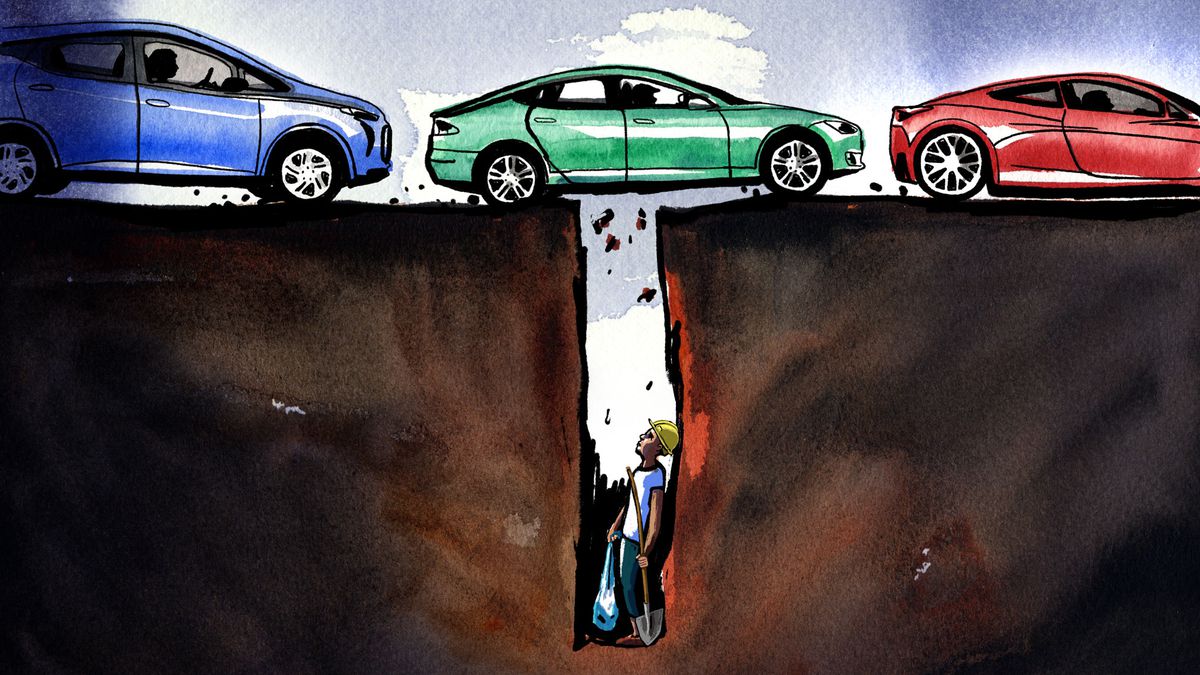

These employees’ accounts are a warning sign that the EV boom is being fueled by exploited labor deep in the supply chain. Mines like KCC are at the center of a geopolitical arms race in which powerful countries and companies are scrambling to acquire the resources needed to dominate the transition to EVs and clean energy — while making investors very rich in the process. But the Congolese workers toiling long hours to wrench this critical mineral from the Earth aren’t getting much in return.

“It is very difficult; I can only fulfill around 25 percent of my needs,” Jean said in an interview with RAID. “If there were other jobs available, I wouldn’t be there.”

In response to detailed questions from RAID about the KCC mine, Glencore emphasized its commitment to worker health and safety, respecting human rights, and “good working conditions and fair salaries,” including for KCC’s suppliers and subcontractors. All direct KCC employees are paid above the DRC’s minimum wage of $3.50 USD per day, the company said, and contractors are also expected to provide “fair remuneration” that is “in line with DRC legislation.” Glencore also said that all KCC employees are supplied with personal protective equipment needed for their jobs and that employees and contractors working underground receive “a minimum” of 1.5 liters of water a day, with an additional 1.2 liters provided to those working 12-hour shifts.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23241324/Industrial_mine_workers_waiting_for_the_company_bus_DRC_2.jpg)

But workers who spoke with The Verge and RAID were more critical of the salaries and working conditions at KCC. In general, workers agreed that the mining company does a good job ensuring workers’ physical safety, although some noted that severe injuries and deaths occur from time to time. (Since 2018, there have been five fatalities at the mine, including two last year, according to Glencore.)

Food and water are a different story: Many workers RAID spoke with, particularly those working underground in the mine, complained of being chronically thirsty on the job due to the labor-intensive nature of the work, high temperatures, and lack of access to taps or fountains inside the mine. A Glencore spokesperson told The Verge that workers can have “as much water as they need” from potable water stations in communal areas.

Monique, who works for a cleaning company contracted by KCC, said that she and her co-workers are not provided with any water and have to ask other KCC employees for it.

“I am often thirsty at work,” Monique, who works about 50 hours a week and earns $350 per month, said in an interview with RAID.

Other employees described going hungry at work. Francois, a KCC employee who works five 12-hour shifts a week, says that he does not have a lunch break and often leaves work without having eaten all day. “I would like to have breaks,” Francois said, but “we are under pressure to produce.” Andre, who also works 12-hour shifts, said that the food quality is “not good” and that there have been no improvements despite complaints from workers.

“The food that is given is not at all comfortable,” said Christian, another KCC employee who works as an electrician. “Many claims have been made but in vain.” Glencore told The Verge that the company provides “a comprehensive, balanced meal” to each mine worker each day.

Many KCC workers interviewed by The Verge and RAID, including some of those employed directly by KCC whose salaries tended to be above $800 a month, said that their earnings were not enough to meet their daily needs. Several also lamented the difficulty obtaining a promotion at the company, alleging that foreigners are hired to fill top positions for salaries far in excess of what the Congolese make.

“They fetch people from elsewhere [for management], which results in no promotion for Congolese,” said Francois. “You can work 10 years and have the same job.”

The difficulty obtaining a promotion is “the negative point of the company,” said Christian, who has worked at KCC for seven years without receiving one.

Glencore told RAID that it is making efforts to boost the number of management positions held by Congolese nationals and that the figure stood at 85 percent as of July 2021. It also said it has promoted more than 3,000 employees in the last five years, most of them Congolese nationals, and that Congolese and non-Congolese employees are “treated equally in terms of benefits and bonuses.” All salaries for foreign and Congolese workers have been “benchmarked and are market competitive,” a spokesperson told The Verge.

The issues raised by workers at KCC are alarming to Anneke Van Woudenberg, the executive director at RAID. But mining companies are often reluctant to make voluntary improvements to their labor practices that could eat into their bottom line, like paying all workers a living wage. Benjamin Sovacool, a professor of energy policy at the University of Sussex who has conducted research on cobalt mining in the DRC, says that companies often match their standards to the requirements of the country they’re operating in: “And Congo has some of the worst best practices there is.”

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23241328/KCC_Uniform_3.jpg)

Compounding the problem, Van Woudenberg says that companies will often tout their adherence to industry human rights standards that target a limited number of issues. For instance, in its most recent impact report, Tesla stated that it only works with cobalt suppliers in the DRC that conform with the Responsible Minerals Initiative Responsible Minerals Assurance Process (RMAP), whose standards focus on forced labor and the worst forms of child labor. While RMAP’s standards are important, they target two “very narrow issues around labor rights,” Van Woudenberg says.

“In effect, the bar is set so low on respect for workers’ rights that it is largely meaningless,” she adds. Tesla disbanded its public relations department in 2019 and no longer responds to questions from reporters.

Sovacool says there’s “obviously more” Glencore can do to improve conditions for workers at the KCC mine. At the same time, he felt that the company is more attuned to labor rights issues than some of its competitors. This impression seems to align with the findings of a recent RAID report, which interviewed workers at KCC as well as four other large industrial mines, including three — Sino-Congolaise des Mines, or Sicomines; Société Minière de Deziwa, or Somidez; and Tenke Fungurume Mining, or TFM —that are majority-owned by various Chinese firms and one, Metalkol, owned by a Luxembourg-based company.

The three Chinese mines provide a steady supply of cobalt to the world’s largest EV market. Desk research by RAID indicates that some cobalt from TFM is also supplied to Umicore’s Kokkola Refinery in Finland and, from there, to Europe’s EV battery supply chain. In December, Umicore and Volkswagen announced a new joint venture to develop EV batteries.

At all of these mines, RAID found a pattern of long working hours, low compensation, and heavy use of subcontracted laborers who tend to earn far less than direct employees. But workers at these other mines also complained of violent abuse, discrimination, and extremely unsafe working conditions. Mine workers described being asked to perform dangerous jobs without proper safety equipment, being told to return to work shortly after experiencing serious injuries, and witnessing preventable deaths. Workers interviewed by RAID also alleged witnessing employees being beaten, kicked, flogged with sticks, and verbally abused by their Chinese supervisors. None of the companies behind these mines responded to requests for comment from The Verge.

“They treated us like animals, not like humans,” said a former employee who worked at TFM as a security guard in 2020, in an interview shared with The Verge.

Investigations like RAID’s put consumer-facing EV companies in a difficult position. A major selling point of EVs is that these cars are better for the planet. But consumers who might be attracted to an EV because of its green credentials could feel differently if they learn that the battery inside it was made with exploited labor.

The reputational risk is severe enough that some companies, like Tesla and General Motors, are exploring new battery chemistries that use less cobalt or replace it with other metals entirely. (Last year, Tesla CEO Elon Musk said on Twitter that the company’s cobalt usage would be “going to zero soon,” although when exactly that will be remains unclear.)

But eliminating cobalt doesn’t change the fact that until the world significantly ramps up EV battery recycling, most battery metals will need to be mined from the Earth. And there are no guarantees that the metals inside a nickel or aluminum-rich battery will be mined under better conditions than cobalt is. At the same time, if powerful players choose to divest entirely from countries like the DRC to avoid reputational damage, that could do more harm to local workers and economies than exploitative mines.

And it may be years before new, cobalt-free batteries that can deliver the same performance as cobalt-rich ones are widely adopted by the industry. While they are in development, the EV boom will continue to accelerate, causing global cobalt demand to rise by up to 20-fold over the next two decades.

As demand surges, advocates like Van Woudenberg are concerned that the plight of Congolese miners will worsen unless the industry is forced to reckon with its labor practices. Mining companies and consumer-facing EV brands both have a responsibility, she says, to apply “much stronger ESG credentials,” including ensuring that all workers in their supply chains are paid a living wage and that none are subject to workplace abuse.

But given the voluntary nature of industry labor standards, Van Woudenberg believes governments will ultimately have to step in and craft new laws and regulations to ensure minerals mined to support the clean energy transition are mined responsibly.

If that doesn’t happen, some of the people least responsible for the climate crisis could wind up paying a steep price to solve it.