Even after central banks recognized they got their inflation calls wrong last year, they’ve continued to flub their policy guidance, threatening greater damage to their credibility, roiling markets and undermining the pandemic recovery.

The Federal Reserve is now expected to hike interest rates by 75 basis points Wednesday, just weeks after Chair Jerome Powell and his team repeatedly advertised a half percentage point move. It’s the latest in a series of misfires, from deeming high inflation “transitory” last year to speeding up the end of its bond-purchase program to accelerating the runoff of its bond portfolio.

European Central Bank President Christine Lagarde has lately also turned more hawkish than she previously indicated, and the Reserve Bank of Australia is among those raising rates faster than policy makers had signaled.

Investors are casting judgment as they fret that the race to make up for past forecasting errors raises the risk of recessions. Global stocks have entered a bear market, US Treasury yields on Monday posted their biggest two-day jump since the 1980s and credit markets are showing signs of increasing stress.

The blunders by monetary mavens tarnish a reputation of ensuring price stability and preventing the kind of inflationary spiral that hammered middle-class incomes in the 1970s. The loss of credibility means even greater policy action may be needed to defuse price pressures.

“Central banks are in a dilemma,” said Sayuri Shirai, a former Bank of Japan board member who’s now a Keio University professor. “To restore confidence, central banks need to raise policy rates” sufficiently to bring down inflation, and that “may lead to a further slowdown in the economic recovery,” she said.

Belief among households and companies that central banks will succeed in meeting their inflation goals over time helps to moderate price pressures. Households might hold off on some purchases, confident some prices will come down in time. And workers would be less likely to embed cost-of-living compensation demands in wage talks.

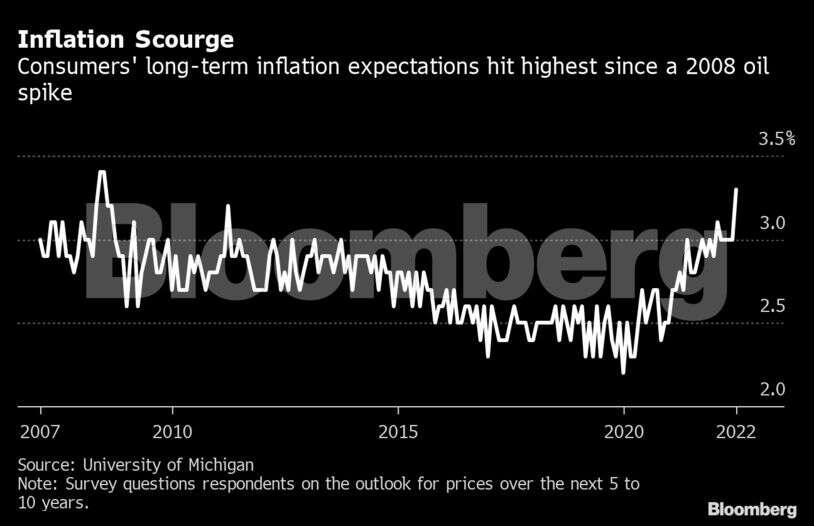

Policy makers until recently highlighted that long-term inflation expectations were contained — a testament to their credibility. Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago President Charles Evans explained in March that current-day inflation wasn’t like the 1980s because “overly accommodative monetary policy” in the 1960s and 1970s had contributed to a buildup of long-term inflation expectations.

Friday’s University of Michigan gauge of longer-term price expectations showed a major crack in that narrative, jumping to the highest since a 2008 oil-price spike.

The Fed, ECB and its peers can’t be blamed for failing to anticipate the price surges stemming from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine or, arguably, the duration of global supply-chain challenges.

Nevertheless, continuing to expand their balance sheets in 2021 and to keep rates near zero even as inflation soared and economies recovered from the depths of the Covid-19 crisis now looks to have helped sow the seeds of current turmoil, critics say.

“That, I believe, will deal a devastating blow to the credibility of central banks — when investors realize that the inflation we face is ‘man-made,’ and central banks have played an instrumental role,” said Stephen Jen, who runs Eurizon SLJ Capital, a hedge fund and advisory firm in London.

Powell took until November to “retire” the description of inflation as “transitory” and last month acknowledged that with “hindsight then, yes, it probably would’ve been better to have raised rates earlier.”

Former Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers, a consistent Fed critic since early 2021, blasted US central bank forecasters’ March expectations for inflation as “delusional when issued.”

The Fed’s preferred price gauge rose an annual 6.3% in April. The median estimate of Fed officials in March was for 4.3% for 2022. Fresh forecasts are due Wednesday.

The US isn’t the only one facing a credibility challenge.

Lagarde and her colleagues are now on course to raise rates by a quarter point in July and 50 basis points in September. That’s after Lagarde said in December it would be unlikely there would be any tightening this year.

“All international institutions, all forecasters of repute have actually made the same mistake” of underestimating the crisis, Lagarde said last week.

RBA Governor Philip Lowe in May said it was “embarrassing” that his previous policy guidance that rates would remain at a record-low until 2024 had proved so wrong.

Among emerging markets, there’s a mixed picture. Some, like Brazil, hiked much faster than developed nations. China has instead focused on offering monetary support amid an economic slowdown.

But in India, the central bank pushed back against suggestions they were behind the curve as recently as April, only to then go on to raise its key interest rate two months in a row. Inflation, meantime, remains well outside its tolerance zone.

For many, polls are showing evidence of public loss of confidence.

A Gallup survey released in May showed just 43% of those polled had a “great deal” or “fair amount” of confidence Powell would do the right thing for the US economy. While not the lowest among recent Fed chiefs, it’s well under the 74% Alan Greenspan got in the early 2000s.

For the first time on record, more people were dissatisfied than satisfied with the performance of the Bank of England when it comes to controlling prices, a quarterly BOE survey showed.

BOJ Governor Haruhiko Kuroda has seen his popularity slump after he said consumers were becoming more tolerant of rising prices. A Kyodo News survey published Monday found 59% deemed him unfit for the job.

Stanley Druckenmiller, who runs Duquesne Family Office, this month warned that because central bank policy a year ago was totally inappropriate, it’s inevitable that investors will lose money.

“If you’re predicting a soft landing, it’s going against decades of history,” said Druckenmiller, 68, who managed money for billionaire George Soros for more than a decade.