Each wave of supply shock to hit the global economy during the pandemic seems to produce a different scapegoat.

First came the shipping container shortage of late 2020, caused largely by American consumers stocking up on everything from backyard games to home-office equipment.

In 2021, companies overordered parts and products to avoid running out, while a series of freak accidents — like the blocking of the Suez Canal — helped shake the global economy close to paralysis.

The first half of this year brought the additional uncertainty of Russian President Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine and China’s strict Covid lockdowns. With the second half of 2022 just underway, there may yet be another culprit for supply stress — labor unrest.

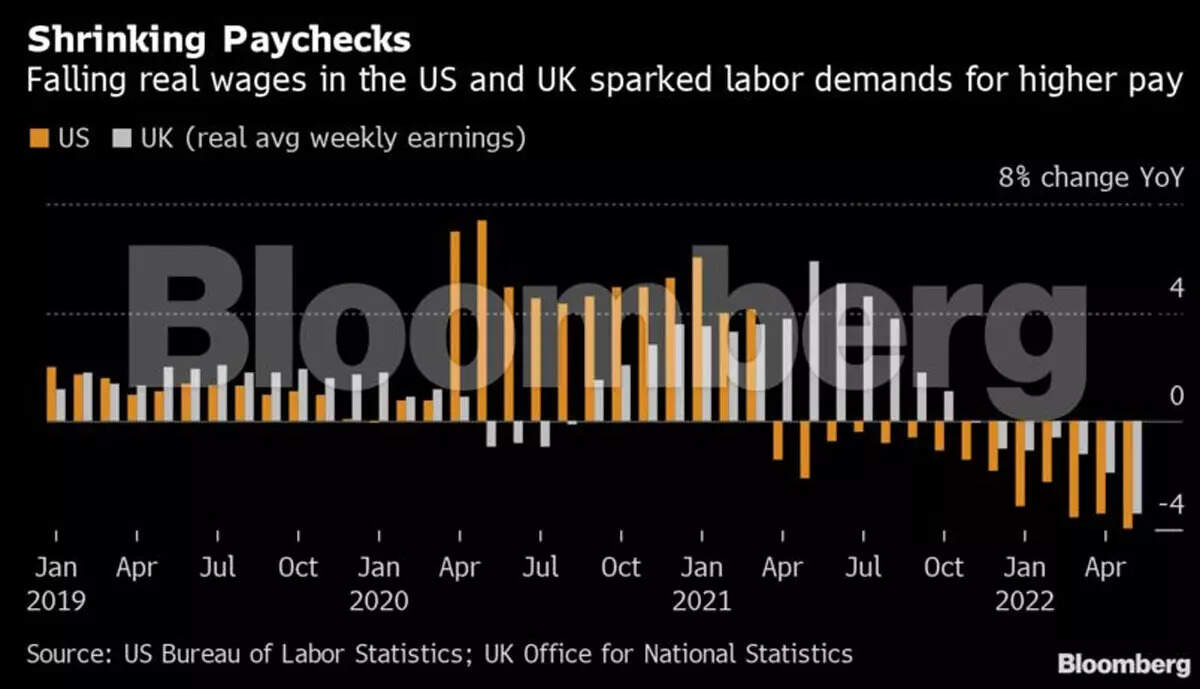

That’s because after years of stagnating wages, workers want to get paid. They’re tired of seeing their incomes evaporate as inflation surges, especially those in logistics or other front-line industries that kept economies functioning during the pandemic. Here’s an example of the pain many are feeling, showing figures on inflation-adjusted earnings receding in the US and UK: Labor is still getting sick in the literal sense and needing to take time off to recover. Ports in northern Europe are among the world’s most congested partly because of Covid outbreaks and sporadic cases of labor stoppages. Using the Bloomberg Terminal’s {MAP <GO>} function, you can see how ship bottlenecks are widening from Antwerp, Belgium, to Hamburg, Germany, as clogged inland rail and trucking networks fail to keep pace with the flow of cargo.

Labor is still getting sick in the literal sense and needing to take time off to recover. Ports in northern Europe are among the world’s most congested partly because of Covid outbreaks and sporadic cases of labor stoppages. Using the Bloomberg Terminal’s {MAP <GO>} function, you can see how ship bottlenecks are widening from Antwerp, Belgium, to Hamburg, Germany, as clogged inland rail and trucking networks fail to keep pace with the flow of cargo.

Even the threat of a major port strike can cause congestion, like the queue of vessels outside the port of Savannah, Georgia — as shown in the map below. Part of the reason is tied to importers rerouting cargo from Asia to avoid any potential labor unrest at the nation’s busiest trade gateways in Los Angeles. The contract for West Coast dockworkers and their employers expired last Friday, and talks are continuing.

As of early this week, there were 31 container ships anchored in the waters off Savannah, leading to waits estimated at eight to 10 days. In the New York area, the delays stretch as long as 20 days for vessels waiting at anchor.

Perhaps the most visible signs of worker discontent appears at airports in the US and Europe, where the passenger carriers are canceling thousands of flights because of shortages of grounds crews, flight attendants and pilots. The return of a healthy summer travel season was supposed to hasten the shift back to normal, but the recovery is hitting some turbulence.

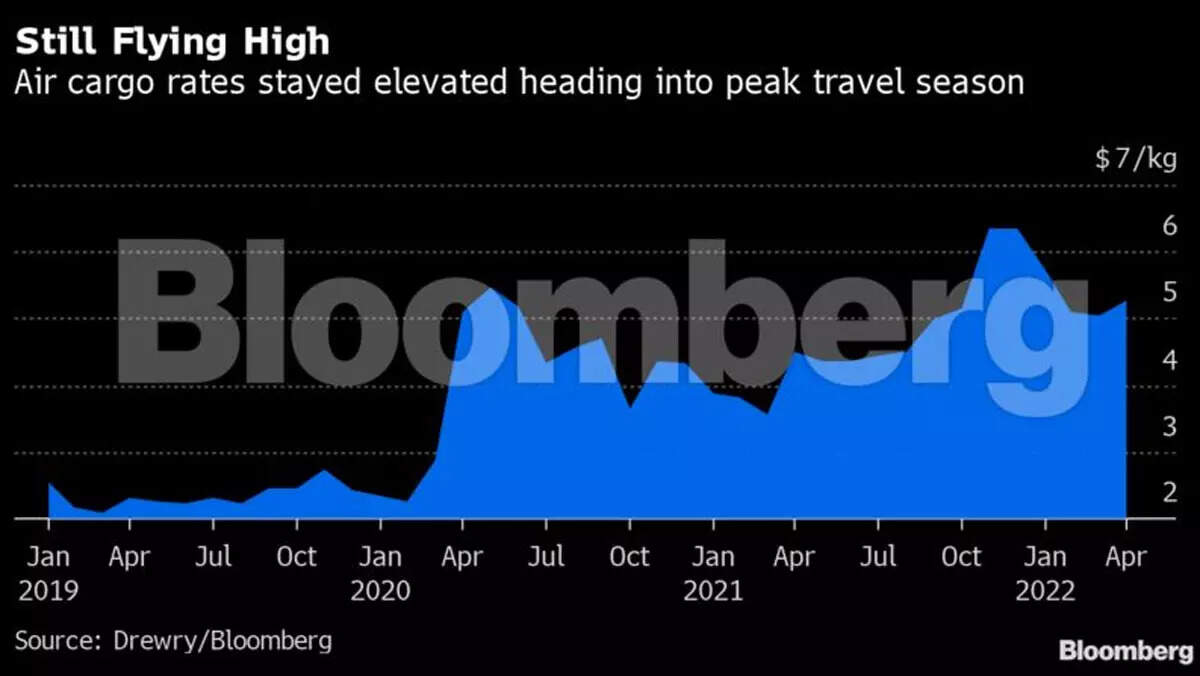

That instability may ripple to the market for air cargo, which tightened considerably over the past two years because so many grounded flights cut capacity in the cargo holds below the passenger cabins. As the Drewry Air Freight index shows, rates have come down some from their peaks, but they’re still more than double pre-pandemic levels. Next thing to watch: how air-freight rates fare when Europe’s temporary rules allowing goods to ride in vacant passenger cabins expire later this month.

Plus, any strike on the US West Coast could boost demand to move goods by plane and send air cargo rates skyward again.