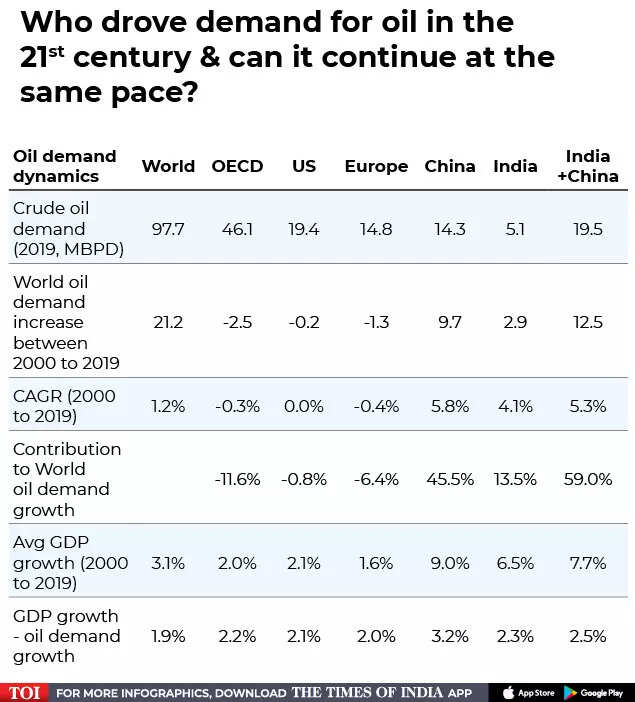

NEW DELHI: China and India together drove the maximum demand for oil in the 21st century.

A whopping 59% of the world’s oil has been driven by China and India between 2000 and 2019, higher than any large country across the same period, noted DSP Investment Managers in a report.

In 2019, China required 14.3 million barrels per day (mbpd) of oil, while India required 5.1 mbpd.

Together, the two nations required 19.5 mbpd.

On the contrary, large economies like the US required 19.4 mbpd while Europe needed 14.8.

And while Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development ( OECD), US and Europe saw their oil demand contract by 2.5%, 0.2% and 1.3% between 2000 and 2019, India and China saw their oil demand rise by 9.7 and 2.9% respectively.

This is primarily because the gross domestic product of China and India grew at a much higher pace than the world and peers between 2000 and 2019. In the next 10 years, the growth rate for both these countries is likely to be lower than the last 20 years.

“Oil demand growth trails GDP growth by about 2% to 2.5%. Assuming China and India growth to slow to 6% & 5% respectively for the next 10 years, oil demand growth is likely to de-grow as well. Therefore, even maintenance of CAPEX could be a threat to prices,” noted the report.

India’s oil thirst

Currently, India is the third largest consumer of crude oil at 5.35 million barrels per day (mbpd), behind US (21.2mbpd) and China (15.1mbpd). India imports nearly 85% of its total crude oil consumption every year.

The country’s own production has been below 700,000 barrels per day for a long time. But India’s energy problems are now tapering as the size of its economy rises.

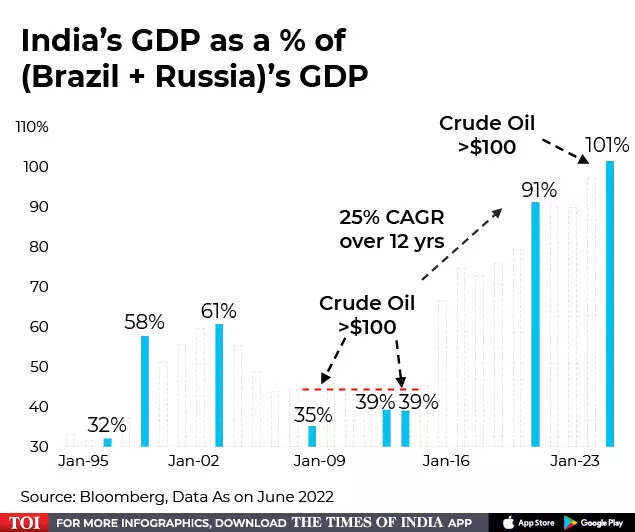

The Indian economy faced debilitating effects from higher oil prices in the past.

On two occasions, when crude oil prices went past $100, the economy slowed appreciably, while the rupee depreciated and bond yields rose.

However, over the years the size of Indian economy has risen swiftly.

It is now as large as the two biggest commodity exporters combined (Russia + Brazil), which means oil prices need to rise a lot more to impact the economy the way it did back in 2008 and between 2011-2014.

The trouble for India: price of oil at this time is beyond $125/barrel for brent crude.

India’s trade deficit—which is difference between the value of its imports and exports—rose to a record $25.6 billion in June 2022, almost three times the figure for the year-ago period driven primarily by higher import value of crude and petroleum products, coal, coke and electronic goods.

A high trade deficit, along with a falling currency, can hurt India’s economy as the current account deficit will widen in the process.

Rating agency ICRA expects the price of the Indian crude oil basket to run in the range of $100-$120 for the remaining period of FY23. The rating agency estimates net oil imports to rise to $145-150 billion from $95.6 billion registered in FY22.

The silver lining

Globally, commodities such as industrial metals and agricultural commodities have seen a sharp decline over the last 3 months, spurred by fears of a looming recession that could tamper demand.

Key industrial metals like copper (-20%), aluminum (-37%) and soft commodities like wheat (-20%) which are closely linked to inflationary trends have faced price erosion.

However, the biggest weight in commodity prices, energy (especially crude oil), is yet to witness a meaningful decline. It is hovering about 10% lower from recent highs.

“Historically, most commodity prices move together. The outliers do not outperform for a long period. It is quite likely that Oil prices will ease in second half of 2022 thereby leading to a change in inflation trajectory in next 6 months,” noted DSP.

Brent crude, the world benchmark, dipped below $100 per barrel for the first time since April before settling at $100.69 earlier on Wednesday.

Analysts say fears of a recession, which could crimp demand for oil and gas, have brought on the price drop.

Central banks across the world are raising interest rates to tame inflation, spurring fears that rising borrowing costs could push countries into recession and reduce oil demand.