Ride-hail startup Alto thinks the current gig worker-based market is inherently broken. Drivers’ salaries are squeezed by the costs of owning and maintaining a vehicle; riders aren’t guaranteed a high-quality service; cities have had to deal with angry taxi drivers; and the app-based companies themselves that have undercharged users to expand into new markets are still not seeing the profits from a growth-at-all costs mindset.

Alto was founded in 2018 to solve those problems by taking more control over the whole ride-hail experience. The startup actually leases its own fleet of ride-hail vehicles, employs drivers and is regulated as a transportation company. Yes, that means it’s more expensive to ride than your average Lyft or Uber, but CEO Will Coleman says Alto isn’t for everybody; it’s for customers who have a higher willingness to both pay and wait for a good thing.

Hence the name — “Alto” means tall, high, elevated or superior in Spanish.

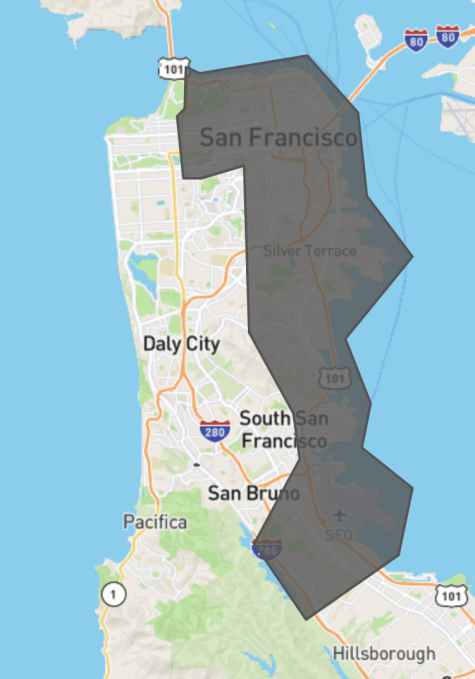

Earlier this month, Alto launched its service in San Francisco, its sixth market across the U.S. The startup also operates in Dallas, Houston, Miami, Washington, D.C. and Los Angeles, and says it is continuing to expand its model. To date, Alto has about 2,000 drivers on its platform driving 400 vehicles, and is awaiting a shipment of 600 more vehicles.

Alto is just one of many new ride-hail startups that are hoping to solve the many flaws of the gig worker model. Revel, for example, has a fleet of Teslas driven exclusively by employees in New York, and Earth is doing something similar in Texas. Meanwhile, worker-owned apps like the Co-Op Ride app is owned collectively by the drivers, which the company says allows drivers to earn 8% to 10% more than those who work for Uber or Lyft.

Alto, which last raised a $45 million Series B in the summer of 2021, says it has grown 420% year-over-year (although the company didn’t say up from what), and attributes this growth to a differentiated level of service.

Map of Alto’s ride-hail service in San Francisco. Image Credits: Alto

“We needed to employ our drivers so that we could not only select and vet, but importantly, train and performance-manage them to drive a consistent high-quality experience for our passengers,” Coleman told TechCrunch. “We own the vehicles so we can clean them, maintain them, keep them safe and ensure that our customer gets the experience that they expect in every single ride.”

The vehicles in Alto’s fleet are all luxury, midsize SUVs — currently Buick Enclaves and VW Atlases — that feature leather interiors, plexiglass partitions and in-vehicle WiFi, according to the company. The goal is to transition to a full EV fleet starting early next year, depending on vehicle availability.

To ensure a smooth transition to EVs, Alto is working on building electric infrastructure charging hubs for its future fleet in all of the cities in which the company currently operates, plus Silicon Valley.

Riders can only access Alto’s service through a membership of $12.95 per month or $99 per year, which Coleman says creates a higher bar to acquisition but one that ensures Alto acquires customers who are more profitable over time because they ride more frequently.

“We don’t have to build to the same peaks that our competitors do,” said Coleman.

While the membership model may be a successful one in the long term, it’s all about how you sell it. Multiple app reviews on the Google Play store and on Apple’s App Store show customers who are disgruntled at being confronted by a request to put in their credit card details immediately upon opening the app, instead of giving them time to play around, review pricing for rides or even determine if Alto services the passenger’s area.

In fact, based on reviews, the app seems to have a number of problems that are putting off users. Over the past year, customers have had problems with pre-booked rides not showing up, the app freezing, inability to get verified, a difficult user interface, no way to contact drivers and more.

“Downloaded, signed up and paid my monthly fee thinking that with employees and such I was paying a premium for a more reliable service,” wrote one app reviewer. “Booked a car for the first time, two days in advance for an airport trip. They no showed and we called and they have no idea why the car isn’t on the way. Ordered a Lyft and it was here before Alto could even figure out what happened. Do not recommend.”

Many reviewers did say their rides were clean and smooth and enjoyed the “vibe” of the service, but were deterred by issues with poor customer service and an unideal app experience.

In response to this, Alto said because it owns and operates its own fleet, capacity is inherently limited.

“The future of ridesharing is in fleets — first electric, then autonomous. In that scenario, supply will always be more constrained than in a gig model,” said Coleman in a follow-up email. “You have to believe that to build a fleet-based, profitable ridesharing company, customers will ultimately be willing to call a ride ~10 minutes ahead (for a better, safer, experience) versus expecting three-minute pickup times.”

Coleman went on to say Alto is constantly working to improve the app experience and grow its fleet to best serve its members.

Employees today, robots tomorrow

“We really think of ourselves as a human-driven autonomous fleet, and then that way we’re also solving for the future,” said Coleman.

Alto’s end game is to create the vehicle-operating platform now that can, in the future, be used with autonomous vehicles. Coleman argues Alto’s tech stack has optimization capabilities that are more cut out for such a transition than Uber and Lyft’s, simply because those companies don’t manage the supply.

“We think about orchestration, how to optimize the best outcome for our entire fleet and customer base, rather than any individual independent contractor, to drive asset utilization and therefore profitability,” said Coleman. “Uber and Lyft have built no operating capability, quite frankly. We’re building the real estate footprint, the charging infrastructure, and just the know-how on how to clean and store and maintain these fleets of hundreds of vehicles in all the cities in which we operate.”

Coleman brings up a good point, namely that it might be easier for a company that has existing operating capabilities to transition to, well, operating a fleet of autonomous vehicles — something that top executives at Uber and Lyft are no doubt crossing their fingers for so they can be done with the pesky problem of dealing with drivers’ rights.

For his part, Coleman doesn’t think either company could even afford to move to an employee-driven model today.

“Their model is predatory towards drivers, and if they can’t make their model sustainable with that, then there’s no way they can make it sustainable with employees,” said Coleman.