European plans to tackle vehicle emissions that cause climate change are at risk of coming undone, sending manufacturers like

Daimler AG back to the drawing board to avoid potential fines.

A series of events over the past weeks have highlighted the region’s struggle to contain greenhouse gases and air pollution, wrong-footing carmakers including

BMW AG and

Volkswagen AG that remain reliant on engines running on diesel.

“It’s safe to say our original premises and plans to meet fleet emissions goals are good for the bin,” said Dieter Zetsche, chief executive officer of Mercedes-Benz maker Daimler. “We think we can meet them still, but it’s not totally up to us but depends on how the customer decides to act.”

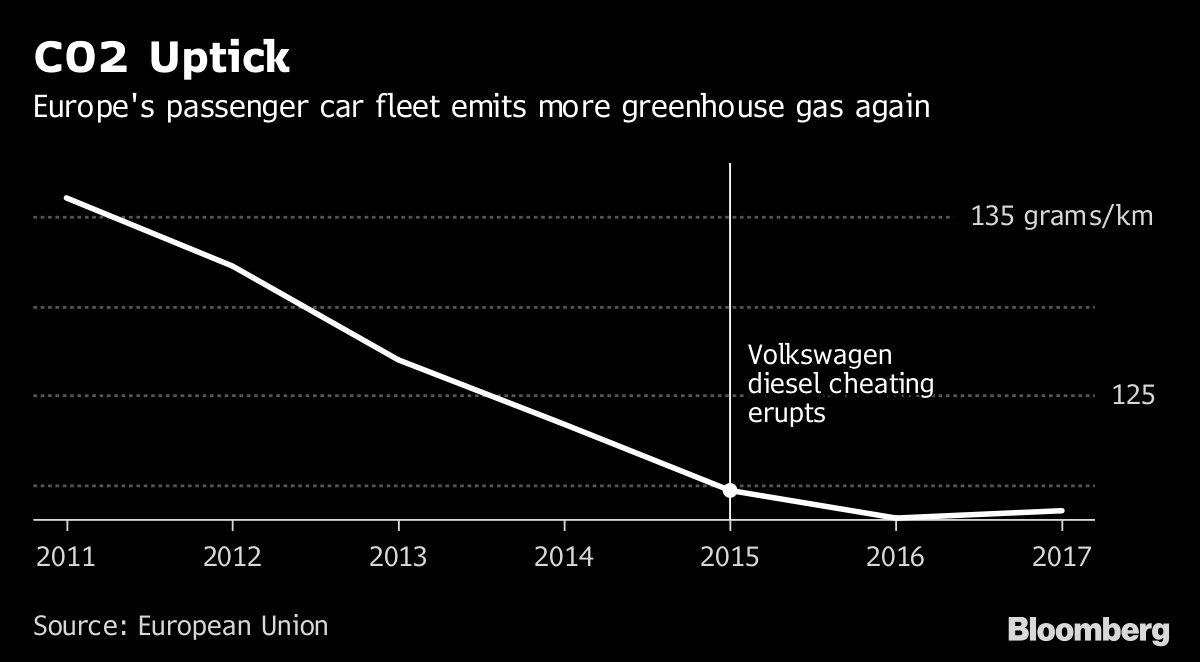

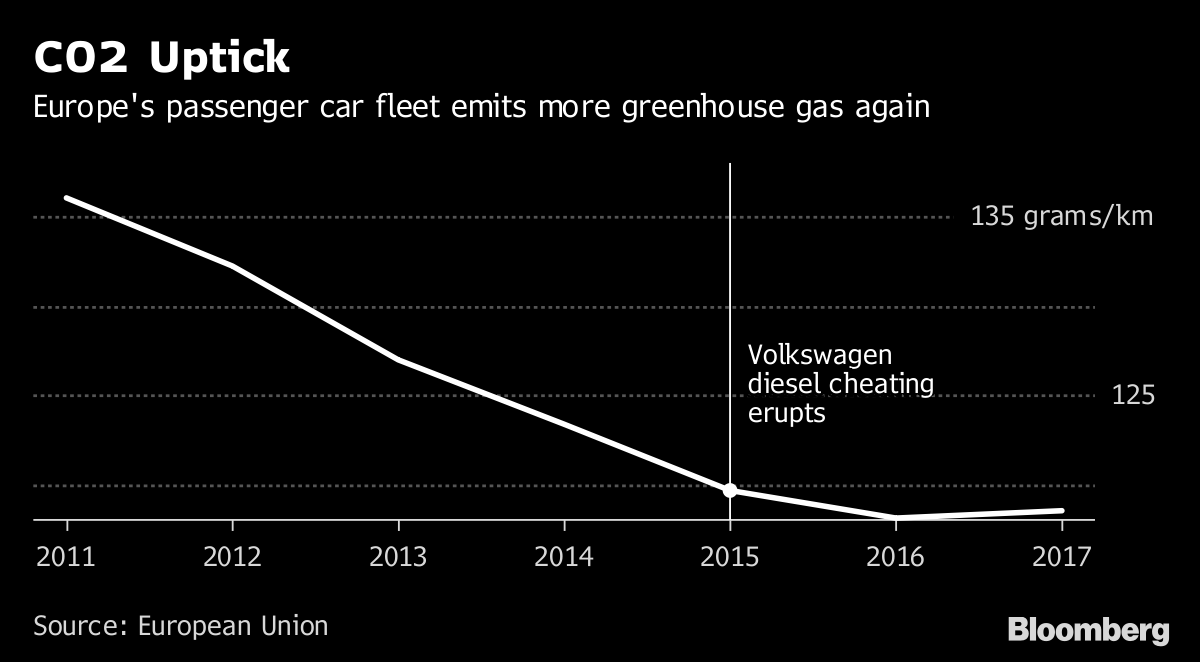

Policies to lower emissions were clouded by the

revelation last month by the European Union that the amount of carbon dioxide produced by new cars rose last year, reversing at least seven years of steady decline of the greenhouse gas in many countries. A further sign of cracks in the system was the bloc’s decision to resort to

suing Germany and five other member states for exceeding air pollution limits. Finally, in a direct blow to carmakers, Hamburg became the first German city to impose

driving restrictions on some cars running on diesel — a fuel that produces less CO2 than gasoline but more harmful air pollutants.

CO2 Uptick

Europe’s passenger car fleet emits more greenhouse gas again

Source: European Union

If manufacturers fail to comply with emissions rules, they are at risk of projected fines of 4.5 billion euros ($5.3 billion), according to study by PA Consulting.

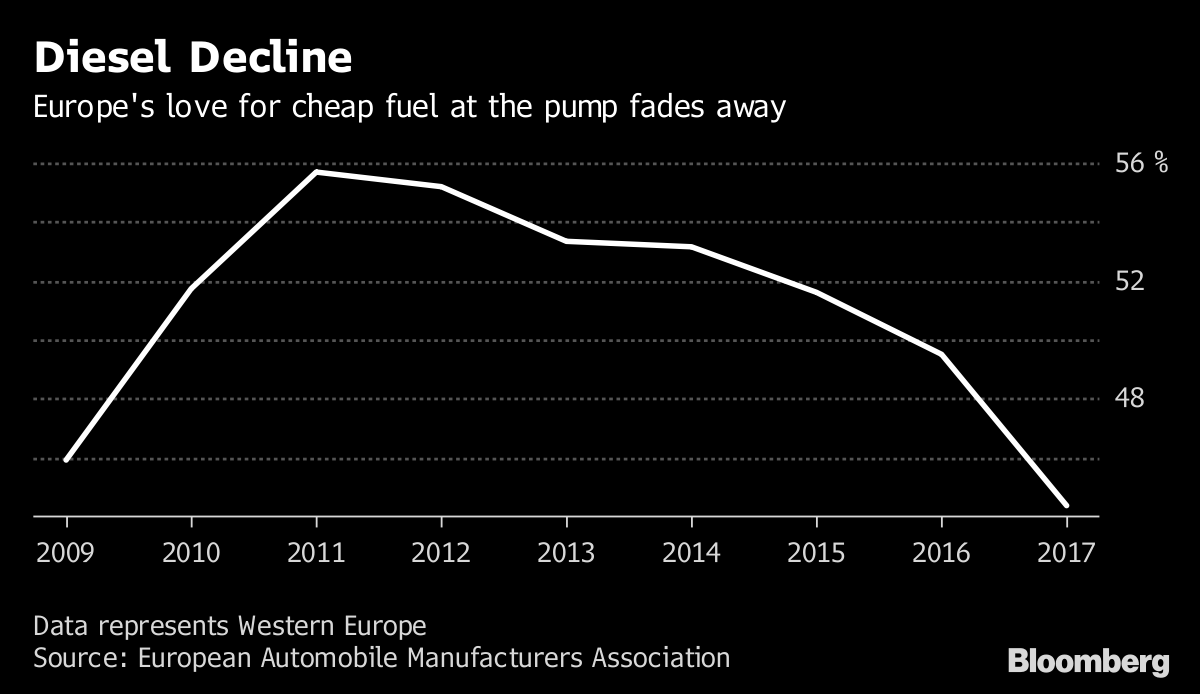

The root of the the European imbroglio over emissions can mostly be traced to Volkswagen’s diesel cheating scandal that erupted in 2015 and caused consumers to shun vehicles running on the fuel partly because of fears they would be

outlawed.

A landmark German court decision in February allowed bans in principle, causing people to give up diesel even faster despite offers from carmakers to clean up older models and take back cars in the event of restrictions.

To read more about diesel’s demise in Europe, click here

Diesel Decline

Europe’s love for cheap fuel at the pump fades away

Source: European Automobile Manufacturers Association

Diesel’s collapse has upended a core plank in the EU’s strategy to lower greenhouse gases: namely to encourage, at least in the short-term, use of the engine technology because it burns hydrocarbons more efficiently than gasoline, thereby cutting carbon emissions.

That policy stemmed from a successful lobbying effort by carmakers in Europe for incentives to make diesel cheaper after the 1997 signing of the global Kyoto protocol climate change agreement, which required signatories to commit to cutting CO2. Manufacturers like BMW, VW and Daimler sought to capitalize on their engineering prowess in diesel technology, while other countries, like Japan, backed research into hybrid and electric cars.

Smog Rises

Lower prices at the pump dramatically boosted diesel’s share by 2006 to over half of all cars sold in Western Europe. But while diesel saves on CO2, it spews out particulate matter and harmful nitrogen dioxide, or NOx, which is expensive to reduce in engines. As diesel proliferated, so did the number of cities failing to meet pollution limits.

Last year, 70 German cities reported excessive levels of NOx, which can cause respiratory problems and premature death. A similar picture emerged in the U.K., France and Italy.

As carbon emissions rise, carmakers are left with two choices — face fines or lower prices for hybrid and electric cars in a bid to jump start sluggish demand. Daimler, for one, is joining rivals in offering electric versions of its vehicles, which don’t emit gases. It’s starting sales of the battery-powered EQ C crossover model next year. A potential damper to sales efforts could be patchy recharging infrastructure for battery-powered cars.

The rise in vehicle-related CO2 emissions is set to get much worse this year, according to Peter Fuss, a partner at consultancy EY. A 0.4 gram increase last year to an average of 118.5 grams per kilometer for new cars sold in the EU highlights the challenge for manufacturers to get within the more stringent 2021 target of 95 grams per kilometer on average. Yet relying on diesel to help is no longer an option, according to the EU’s industrial-policy chief.

“Diesel cars are finished,” European Commissioner Elzbieta Bienkowska said in a May 24 interview. “I think in several years they will completely disappear. This is the technology of the past.”

To read about her views on the future of the region’s car sector, click here

— With assistance by Ewa Krukowska