Last month, Waymo launched its first self-driving taxi service — Waymo One — in Phoenix, Arizona, but you would hardly know it by scrolling through your feed. No Facebook posts, no live-streaming videos, no tweets. We don’t know how many people are using the Google offshoot’s self-driving minivans (Waymo won’t say), but the ones that are have been surprisingly mute on social media.

One exception is Shawn Metz, a 30-year-old HR manager who lives in Chandler, Arizona. Since he was invited to use Waymo One in December, Metz has posted at least a dozen videos on Instagram and YouTube, documenting his experience using Waymo’s self-driving minivans.

He’s become the hero of AV enthusiasts on Reddit for his willingness to answer questions and post unedited videos of his rides. And Waymo, never one to pass up a marketing opportunity, has even featured a softball interview with Metz on its Medium page.

“You would think that if you were in an autonomous vehicle, you would be posting all over social media,” Metz told me after I asked him why he appeared to be the only person posting photos and videos of his trips with Waymo One.

To be sure, Metz is part of a very exclusive club. For a few months in 2018, he was a member of Waymo’s Early Rider program, a group of 400 or so residents of the Phoenix area selected by the company to beta test its self-driving taxi service. Waymo has tightly controlled information about the project, contractually prohibiting Early Riders from discussing their experiences. Waymo One passengers are all former Early Rider, but are not subject to non-disclosure agreements.

“The opportunity to be able to have conversations like this, and share some of our feedback about it, was actually pretty exciting,” Metz said.

Metz says he and his wife use Waymo One around six to eight times a week, for trips to the grocery store, restaurants, or when he knows he’s going somewhere with limited parking. Interestingly, he never used Uber or Lyft prior to signing up with Waymo, and only downloaded the Uber app to compare fares with Waymo One. (“They’re awfully close. I think it was about 20 cents cheaper with Waymo.”)

His vehicle of choice is a bicycle, which he uses to commute nine miles to work as an HR manager in Tempe most days. But on those days when it’s too hot to bike — it got up to 122 degrees in Phoenix last year — Metz will take Waymo One.

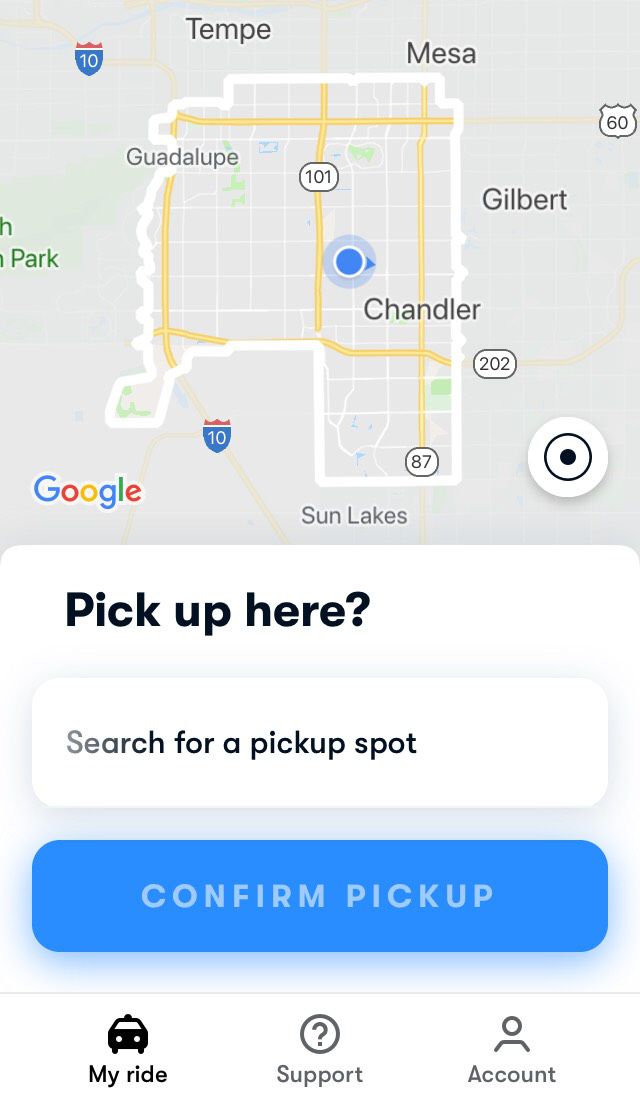

While Waymo has been fairly transparent about some aspects of its business, there is still much we don’t know about it. Specific details, like the number of customers currently using Waymo One, the exact geography of its service area, and when the company expects to remove human safety drivers from behind the wheel, are a big question mark. Waymo says “hundreds” of Early Riders are in the process of being invited to use Waymo One, and the service area of “around 100 square miles” includes the towns of Chandler, Mesa, Tempe, and Gilbert.

There have also been questions raised about the quality of Waymo’s self-driving technology. According to a report in The Information, Waymo’s most advanced vehicles are still occasionally confounded by certain traffic situations, such as unprotected left turns. This suggests the tech — while incredibly advanced — is still not quite ready for the real world.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/13697903/IMG_7698.jpeg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/13697890/IMG_7700.jpeg)

Metz shared a couple screenshots from the Waymo One app, which shows the geography of the service area and some of the accessibility features that are offered. He told me that one question he frequently gets asked is whether Waymo’s vehicles avoid taking freeways. Initially he told me it’s not a question he can really answer, as most of the trips he takes with Waymo One don’t require freeway driving. But after our interview, he sent me a video of a recent nighttime trip that he took from US-60 to Loop 101, after getting a flat tire on his bike.

(He even managed to squeeze his damaged bicycle in the minivan, despite not having access to the vehicle’s trunk. “With the wheels removed, it fits between the captain’s chairs!” Metz wrote on Reddit. “However, I’m not sure that I would do it again. I messaged Waymo Support and profusely apologized after the ride because I think I got some dirt on the ceiling taking it out.”

He recalled a handful of moments when the Waymo vehicle appeared confused by certain situations, such as a crowded parking lot outside Costco. “I was really ambitious and I tried to take it to Costco on the weekend during the holiday season,” he said. “And basically we essentially got kind of stuck outside of entrance.” After several minutes of failing to find a gap through the number of pedestrians streaming in and out of the store, Metz said the vehicle “timed out” and the safety driver had to call Waymo’s remote support center for re-routing help.

Waymo’s remote support workers, located in offices in Phoenix, Mountain View, and Austin, Texas, provide an additional layer of oversight for its autonomous vehicles, with access to video feeds from more than a half-dozen cameras mounted outside and one inside the vans.

Inclement weather, and rain specifically, poses another problem. Metz said he hailed a Waymo vehicle during a recent rainstorm, and when he got in, discovered that the company’s human monitor was driving the car manually. But Metz said he doesn’t fault Waymo for being overly cautious, nor does he sympathize with Phoenix residents who have complained about getting stuck behind a slow-moving self-driving car. “If you’re tailgating and doing ten over [the speed limit], then yeah, you’re going to be angry,” he said.

Recent reports of Waymo vehicles being attacked with knives and rocks by irate Arizonians were shocking to Metz, who says he has never encountered any belligerence while riding in the autonomous vehicles. Chandler police have logged nearly two dozen incidents over the last two years, The Arizona Republic reports. “It is Arizona,” Metz said, laughing.

Pickups and drop-offs with Waymo are fairly seamless, he said, though there was one incident when the minivan dropped him off on the wrong side of the street. “The driver put it in manual mode just because our trip already ended, to take us across the street,” he said.

Tiny corrections like that will become more complicated when Waymo removes its human safety drivers from the vehicles, as is ultimately the goal. Waymo was criticized when it launched Waymo One with human monitors behind the wheel. Some felt the service had been over hyped. The limited rollout of Waymo One has helped reinforce the growing perception that self-driving cars — truly driverless ones that need zero human input within a specific area — are still a long way in the future.

Metz, for one, is happy to wait. The fact that Waymo One isn’t truly driverless doesn’t bother him. At least not yet.

“I would actually like to see the safety drivers stay in the vehicles, for at least another three to six months,” he said. Metz said he wouldn’t know what do as a passenger if the vehicle got stuck, or created a traffic incident, without a human backup driver to take the wheel. “With how much is riding on the technology, I’d rather wait three to six months than have the technology get set back another decade or something because of something happening.”

Metz isn’t an engineer or an expert in computer vision or artificial intelligence. He’s just the guy in the backseat, enthusiastic about the technology, but also keen to get to where he’s going in one piece.