United Auto Workers called a strike on Sunday for the first time in over a decade as contract negotiations reached an impasse

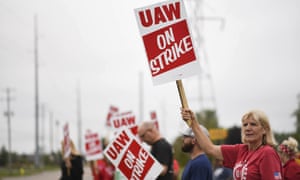

United Auto Workers (UAW) members picket at a gate at the General Motors Flint Assembly Plant on Monday.

Photograph: Bill Pugliano/Getty Images

Uncertainty, apprehension and stress were the words people picketing General Motors workers at the car company’s sprawling Detroit-Hamtramck assembly plant used to describe day one of their strike.

If the strike by United Auto Workers (UAW) members drags on, they could soon end up earning just $250 per week, and there’s fear about what that could mean for their families. But picketers who spoke with the Guardian say they’re also certain about their mission, and accept the need to “sacrifice” while standing up to what line worker James Cotton called “flat out greed” on management’s part.

The UAW called a strike on Sunday for the first time in over a decade as negotiations reached an impasse. Talks began again Monday. Cotton and other workers insist they’re not just there for the 49,000 union employees at GM’s US plants and distribution centers, but for workers across America who aren’t sharing in high corporate profits, as well as their families and their communities.

“We got families to feed, bills to pay just like anyone else, and that’s tough on us, but we have to do what we have to do to make us stronger in the long run,” Cotton said. “It’s not about me, it’s about our kids and families and the people who are coming after us, and our fathers and grandfathers who fought for us before. It’s about all of them, and we don’t want to go backwards.”

Keneisha Williams, who has been with the automaker for four years, echoed that: “We’re fighting for all American workers.”

Willams and Cotton were among several dozen workers picketing and chanting outside each of three entrances around the quiet plant on Monday morning. Striking employees waved signs to a loud chorus of horns from passing cars, trucks, fire engines, rigs and more. Union Ford employees and Detroit police officers dropped off pizza, Dunkin’ Donuts, and cases of bottles of water while offering verbal encouragement.

As they picketed on the side of the deteriorating road that rings the Detroit-Hamtramck plant, workers repeatedly pointed to GM’s strong profits and the concessions made by the UAW in 2007 as the company headed toward its 2009 bankruptcy and bailout.

Over the last two and a half years, the company pulled in over $25bn in profits, while CEO Mary Berra’s $22m 2018 salary – 281 times that of the median GM worker – irked those on the line. The profits come as GM shed 22,000 jobs around the globe during its 2018 restructuring, including 2,800 active hourly positions, while thousands more workers remain at risk. The restructuring is estimated to save GM $2bn.

“It’s like David and Goliath,” Cotton said. “When you’re making more money than you ever made and you don’t want to give some of that to the little guy – that’s not fair.”

UAW Local 22 president Wiley Turnage, who leads about 700 members that work at the plant, added that the workers are prepared to make “a sacrifice and we have to stand up for the things that we need,” including job security and better wages.

“The corporation is making a lot of money and they need to invest some of it back into us,” he said.

Michael Burson, a 15-year company veteran who now works in the plant’s body shop, summed up frustration with the 2007 concessions and company’s recent return to profitability: “They went bankrupt because of poor management and that had nothing to do with us. Now they’re not having a problem making money, and they need to share that.”

Workers here are also focused on what several characterized as “equality” for all employees, including temporary workers and those in different tiers, said Chaz Akers. The West Virginia native moved to Michigan five years ago to work for the automaker and installs passenger side headlights.

Akers said his coworker on the line who installs the drivers side headlights is a temp worker who has been employed for several years, but earns less than Akers, doesn’t receive good benefits, has very few sick days, and generally “gets treated like dirt”.

Akers charged that GM’s heavy reliance on temp workers who maintain that status for years is part of a plan to avoid paying the employees better wages and offering good benefits. He said any new contract must include “a clear path to permanent employment for temp workers”, and called GM’s regular use of temps an attempt “to sow division among the workforce”.

“If I was in management, then I would do that to try to divide the union as much as possible, make it as weak as possible, so I could get as much concessions as possible,” Akers said.

Detroit-Hamtramck employees are also anxious to save their plant, which is among four GM plans to idle as part of the restructuring. It’s slated to close in January, and only around 800 employees remain, though it’s rumored that the automaker is willing to discuss keeping the plant open.

When the UAW last struck in 2007 for three days, its ranks included 22,000 more members.

“We’ve lost lost a lot of union jobs in the area, and all we want is job security, and decent income to support our families and communities,” said Joel Petrimouls, a registered nurse in the plant.

Others voiced frustration with GM for sending jobs to and investing in Mexico, where it’s now the largest auto employer.

“They’re not closing plants in Mexico, they’re growing them, but we need the work here,” Burson said, while plant safety trainer Simon Dandu called GM’s reliance on Mexican and Chinese workforces a “slap in the face”.

Local 22 president Turnage said his “main concern is jobs”.

“We need job security. We have a lot of young, growing families here and we need work for them,” he said. “We have four plants closing … and that would be devastating for the community around us, too.”

GM opened the Detroit-Hamtramck plant in 1985 with the help of hundreds of millions in local, state, and federal tax incentives. It also razed an entire neighborhood and forced thousands of residents from their homes to make way for the plant. Cotton alluded to that controversy on Monday morning.

“Everyone has bent over backwards for General Motors, whether it’s losing wages, losing benefits, homes, businesses – but what do we all get back?” he asked.