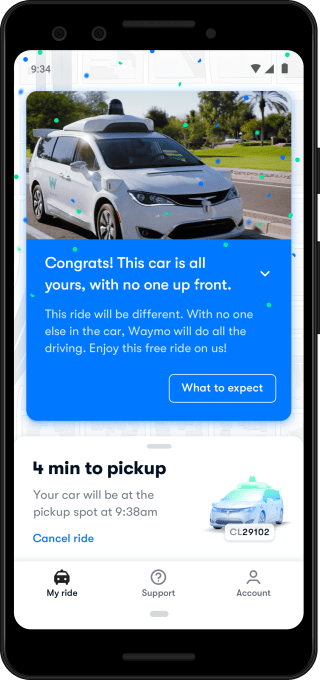

“Congrats! This car is all yours, with no one up front,” the pop-up notification from the Waymo One app reads. “This ride will be different. With no one else in the car, Waymo will do all the driving. Enjoy this free ride on us!”

Moments later, an empty Chrysler Pacifica minivan appears and navigates its way to my location near a park in Chandler, the Phoenix suburb where Waymo has been testing its autonomous vehicles since 2016.

Waymo, the Google self-driving-project-turned-Alphabet unit, has given demos of its autonomous vehicles before. More than a dozen journalists experienced driverless rides in 2017 on a closed course at Waymo’s testing facility in Castle; and Steve Mahan, who is legally blind, took a driverless ride in the company’s Firefly prototype on Austin’s city streets way back in 2015.

But this driverless ride is different — and not just because it involved an unprotected left-hand turn, busy city streets or that the Waymo One app was used to hail the ride. It marks the beginning of a driverless ride-hailing service that is now being used by members of its early rider program and eventually the public.

But this driverless ride is different — and not just because it involved an unprotected left-hand turn, busy city streets or that the Waymo One app was used to hail the ride. It marks the beginning of a driverless ride-hailing service that is now being used by members of its early rider program and eventually the public.

It’s a milestone that has been promised — and has remained just out of reach — for years.

In 2017, Waymo CEO John Krafcik declared on stage at the Lisbon Web Summit that “fully self-driving cars are here.” Krafcik’s show of confidence and accompanying blog post implied that the “race to autonomy” was almost over. But it wasn’t.

Nearly two years after Krafcik’s comments, vehicles driven by humans — not computers — still clog the roads in Phoenix. The majority of Waymo’s fleet of self-driving Chrysler Pacifica minivans in Arizona have human safety drivers behind the wheel; and the few driverless ones have been limited to testing only.

Despite some progress, Waymo’s promise of a driverless future has seemed destined to be forever overshadowed by stagnation. Until now.

Waymo wouldn’t share specific numbers on just how many driverless rides it would be giving, only saying that it continues to ramp up its operations. Here’s what we do know. There are hundreds of customers in its early rider program, all of whom will have access to this offering. These early riders can’t request a fully driverless ride. Instead, they are matched with a driverless car if it’s nearby.

There are, of course, caveats to this milestone. Waymo is conducting these “completely driverless” rides in a controlled geofenced environment. Early rider program members are people who are selected based on what ZIP code they live in and are required to sign NDAs. And the rides are free, at least for now.

Still, as I buckle my seatbelt and take stock of the empty driver’s seat, it’s hard not to be struck, at least for a fleeting moment, by the achievement.

It would be a mistake to think that the job is done. This moment marks the start of another, potentially lengthy, chapter in the development of driverless mobility rather than a sign that ubiquitous autonomy is finally at hand.

Futuristic joyride

A driverless ride sounds like a futuristic joyride, but it’s obvious from the outset that the absence of a human touch presents a wealth of practical and psychological challenges.

As soon as I’m seated, belted and underway, the car automatically calls Waymo’s rider assistance team to address any questions or concerns about the driverless ride — bringing a brief human touch to the experience.

I’ve been riding in autonomous vehicles on public roads since late 2016. All of those rides had human safety drivers behind the wheel. Seeing an empty driver’s seat at 45 miles per hour, or a steering wheel spinning in empty space as it navigates suburban traffic, feels inescapably surreal. The sensation is akin to one of those dreams where everything is the picture of normalcy except for that one detail — the clock with a human face or the cat dressed in boots and walking with a cane.

Other than that niggling feeling that I might wake up at any moment, my 10-minute ride from a park to a coffee shop was very much like any other ride in a “self-driving” car. There were moments where the self-driving system’s driving impressed, like the way it caught an unprotected left turn just as the traffic signal turned yellow or how its acceleration matched surrounding traffic. The vehicle seemed to even have mastered the more human-like driving skill of crawling forward at a stop sign to signal its intent.

Only a few typical quirks, like moments of overly cautious traffic spacing and overactive path planning, betrayed the fact that a computer was in control. A more typical rider, specifically one who doesn’t regularly practice their version of the driving Turing Test, might not have even noticed them.

How safe is ‘safe enough’?

Waymo’s decision to put me in a fully driverless car on public roads anywhere speaks to the confidence it puts in its “driver,” but the company was cagey about the specific source of that confidence.

Waymo’s Director of Product Saswat Panigrahi declined to share how many driverless miles Waymo had accumulated in Chandler, or what specific benchmarks proved that its driver was “safe enough” to handle the risk of a fully driverless ride. Citing the firm’s 10 million real-world miles and 10 billion simulation miles, Panigrahi argued that Waymo’s confidence comes from “a holistic picture.”

“Autonomous driving is complex enough not to rely on a singular metric,” Panigrahi said.

It’s a sensible, albeit frustrating, argument, given that the most significant open question hanging over the autonomous drive space is “how safe is safe enough?” Absent more details, it’s hard to say if my driverless ride reflects a significant benchmark in Waymo’s broader technical maturity or simply its confidence in a relatively unchallenging route.

The company’s driverless rides are currently free and only taking place in a geofenced area that includes parts of Chandler, Mesa and Tempe. This driverless territory is smaller than Waymo’s standard domain in the Phoenix suburbs, implying that confidence levels are still highly situational. Even Waymo vehicles with safety drivers don’t yet take riders to one of the most popular ride-hailing destinations: the airport.

The complexities of driverless

Panigrahi deflected questions about the proliferation of driverless rides, saying only that the number has been increasing and will continue to do so. Waymo has about 600 autonomous vehicles in its fleet across all geographies, including Mountain View, Calif. The majority of those vehicles are in Phoenix, according to the company.

However, Panigrahi did reveal that the primary limiting factor is applying what it learned from research into early rider experiences.

“This is an experience that you can’t really learn from someone else,” Panigrahi said. “This is truly new.”

Some of the most difficult challenges of driverless mobility only emerge once riders are combined with the absence of a human behind the wheel. For example, developing the technologies and protocols that allow a driverless Waymo to detect and pull over for emergency response vehicles and even allow emergency services to take over control was a complex task that required extensive testing and collaboration with local authorities.

“This was an entire area that, before doing full driverless, we didn’t have to worry as much about,” Panigrahi said.

The user experience is another crux of driverless ride-hailing. It’s an area to which Waymo has dedicated considerable time and resources — and for good reason. User experience turns out to hold some surprisingly thorny challenges once humans are removed from the equation.

The everyday interactions between a passenger and an Uber or Lyft driver, such as conversations about pick-up and drop-offs as well as sudden changes in plans, become more complex when the driver is a computer. It’s an area that Waymo’s user experience research (UXR) team admits it is still figuring out.

Computers and sensors may already be better than humans at specific driving capabilities, like staying in lanes or avoiding obstacles (especially over long periods of time), but they lack the human flexibility and adaptability needed to be a good mobility provider.

Learning how to either handle or avoid the complexities that humans accomplish with little effort requires a mix of extensive experience and targeted research into areas like behavioral psychology that tech companies can seem allergic to.

Not just a tech problem

Waymo’s early driverless rides mark the beginning of a new phase of development filled with fresh challenges that can’t be solved with technology alone. Research into human behavior, building up expertise in the stochastic interactions of the modern urban curbside, and developing relationships and protocols with local authorities are all deeply time-consuming efforts. These are not challenges that Waymo can simply throw technology at, but require painstaking work by humans who understand other humans.

Some of these challenges are relatively straightforward. For example, it didn’t take long for Waymo to realize that dropping off riders as close to the entrance of a Walmart was actually less convenient due to the high volume of foot traffic. But understanding that pick-up and drop-off isn’t ruled by a single principle (e.g. closer to the entrance is always better) hints at a hidden wealth of complexity that Waymo’s vehicles need to master.

As frustrating as the slow pace of self-driving proliferation is, the fact that Waymo is embracing these challenges and taking the time to address it is encouraging.

The first chapter of autonomous drive technology development was focused on the purely technical challenge of making computers drive. Weaving Waymo’s computer “driver” into the fabric of society requires an understanding of something even more mysterious and complex: people and how they interact with each other and the environment around them.

Given how fundamentally autonomous mobility could impact our society and cities, it’s reassuring to know that one of the technology’s leading developers is taking the time to understand and adapt to them.