Will Ohio’s Voltage Valley energize a new era for the US auto industry?

Big things are happening in the Mahoning Valley area of northeastern Ohio. The region, which centers on the city of Youngstown, was a booming center of steel production until the 1970s. Since then, like many other industrial hubs, the area has suffered from a long, gradual decline. When the GM plant in Lordstown, at which some 5,000 workers had produced the Chevy Cruze, closed in early 2019, locals called it Black Monday.

Things soon started to look a bit sunnier, as GM sold the plant to Lordstown Motors, founded by Steve Burns, who previously founded Workhorse Group, an EV builder that’s been around since 1998, and has supplied electric vans to UPS, FedEx and other fleet operators (we ran a feature article on the company in our May/June 2017 issue). Lordstown plans to begin production of an electric pickup at the plant starting in late 2020. Meanwhile, Workhorse continues building electric vans, and GM and LG Chem have announced plans to invest up to $2.3 billion in a battery cell assembly plant in the area. As an ecosystem of EV-related industries begins to develop in the area, some are now calling it Voltage Valley.

Steve Burns was Workhorse’s CEO until late 2019, when he left the company to start the new Lordstown Motors. As you can imagine, he’s a busy man these days. Charged recently chatted with Burns to learn more about the company’s plans.

GM has not invested any cash in Lordstown Motors—it just sold the new company its plant. However, it’s undeniable that GM has invested a chunk of corporate prestige in the deal, and has a vested interest in seeing its former employees find new jobs. The compelling story of a shuttered plant being resurrected by the growing clean energy economy has attracted a lot of press coverage. With the case for commercial EVs growing more compelling by the day, the future for Lordstown Motors looks bright.

Charged: The last time we spoke with you, Workhorse was working on an electric pickup. Now that project has been transferred to Lordstown. What was the rationale for that?

Steve Burns: Workhorse’s primary business is building big electric delivery vans. We realized there’d be a good audience for an electric pickup truck. This was four years ago, and we originally planned on building a plug-in hybrid. We got a very good response—we got some pre-orders from fleets, big fleets, and we started to go down that road, but bringing a pickup truck to market is different than a large UPS van. There are a lot more regulatory issues around it—airbags, crash testing and that sort of thing. It’s a fairly expensive endeavor.

With all the attention they were getting around their delivery vans and the post office bid [Workhorse is one of several companies in the running to provide a new delivery vehicle for the US Postal Service], and the explosion of Amazon and all the last mile delivery stuff, it just made all the sense in the world for Workhorse to focus on just delivery vans.

So, I left Workhorse and formed a new company, specifically to do electric pickup trucks. We purchased the still-warm Chevy Cruze plant in Lordstown, Ohio, and it took about a year to negotiate that. Now we’re retooling it. We’ve been engineering hard for a year.

Our Endurance pickup truck is all electric, and it has a lot of advances. In the last four years, everything’s changed, and we wanted to use all the newer stuff. Our battery pack is very advanced and we’re really excited about it, but battery packs are kind of a given these days. They’re not rocket science anymore, until the next generation [of solid-state batteries] comes out, and then there will be a new wave of innovation.

What really sets us apart is this hub motor configuration. Only four moving parts in the drive train—just the four wheels. It’s super simple—it’s the simplest car ever made. Simpler than a Model T, simpler than a Tesla. There’s not a gear in the vehicle, there’s not a U-joint, a drive axle, a differential, none of that. If you fast forwarded and said, “What’s the simplest, most efficient vehicle?” The answer is: no moving parts except the four wheels. When you do that, you can start with a blank sheet of paper. If I don’t have anything down the middle of the vehicle, can I make it crash test better? Can I make it handle better? The battery pack’s low, but I also have this low weight of the motors, literally right on the ground. It is unsprung mass, and you’ve got to accommodate that. We had to build a suspension and a chassis from scratch that could accommodate a battery pack in between the rails and not just handle the unsprung mass, but make it handle better than any other pickup truck. We started testing the premise of our chassis and our suspension and our software on a test track, and it handles like a sports car. It’s unbelievable.

Charged: Tell us about your current relationship with Workhorse.

Steve Burns: They own 10% of Lordstown. Also, we have a royalty agreement for every vehicle—we pay them a royalty for some of the technology of theirs that we’re using in our trucks—and they have a board seat.

Charged: Is the Lordstown Endurance an evolution of the Workhorse W-15 electric pickup truck design?

Steve Burns: No, the W-15 was what started us thinking about pickup trucks, but the W-15 [didn’t use] a hub motor, and the W-15 was a plug-in hybrid. So it’s pretty different.

Charged: Can you talk me through the purchasing of the plant? You said that GM went above and beyond to sell the plant to a firm that would keep it running.

Steve Burns: Automotive plants come up for sale very infrequently. When we were one of the bidders for the plant, we requested that GM keep it intact, because we’re in a hurry, we want to be first to market with the first electric pickup truck, and if we had to retool it, [it would be tougher financially]. This recipe has been followed a few times. Tesla bought a shuttered plant from GM and Toyota, called the NUMMI plant, out in California [now the company’s Fremont factory]. Rivian bought a five-year-old shuttered plant from Mitsubishi [in Normal, Illinois].

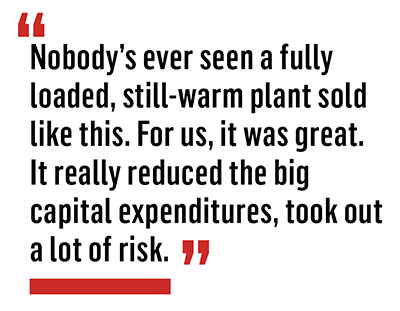

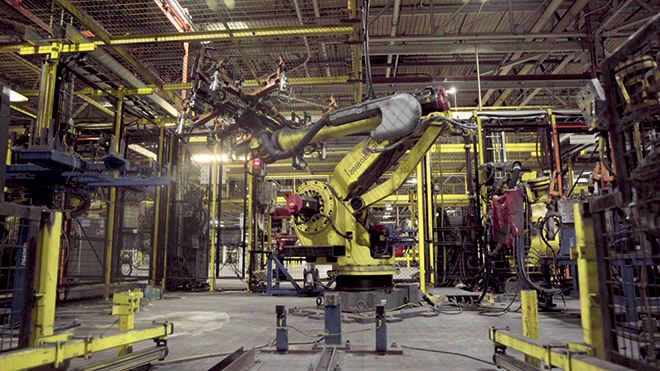

Both of those plants were mostly gutted, because the parts in there can be used in other plants. The robots, paint booths, stamping presses, are all common components. These are very expensive to buy, so when a plant is shuttered, usually the OEM takes out the components to put in another place. Nobody’s ever seen a fully loaded, still-warm plant sold like this. For us, it was great. It really reduced the big capital expenditures, took out a lot of risk. And even if you’ve got a squeaky-clean plant with a nice gray floor, there’s still execution risk. Did you buy the right equipment? Does it all dance together when you orchestrate a dance, all the robots? It’s a lot of expenditure and a lot of risk. It’s why there aren’t really small car companies.

That plant made somewhere around 427,000 Cruzes a year. It’s a very high volume, and to produce that many vehicles, you have to have a lot of high-end equipment—it all has to be good at that level. A lot of stamping, a lot of welding, a lot of robots, a lot of assembly. So, to get that was really a gem, and it is in a factory town or a factory region. Naturally, there’s a lot of great talent here. If we’re in a hurry, where else are you going to find thousands of skilled workers that can put cars together? So, we’ve got a great plant and we’ve got a very excited workforce that wants to get back to work building cars. It’s really perfect.

Charged: How big of an engineering challenge is it to specialize this manufacturing equipment for your needs?

Steve Burns: Fortunately, there is a commonality of robots. They’re not very specialized. They’re industrial, automotive-grade robots and it’s a known science how to program them. We’ve got a lot of high-end production engineers on our team who formerly worked for Volkswagen, Toyota, Ford, Karma, and a lot of Tesla guys. We had to get the best of both worlds: old-school, because there’s 100 years of tribal knowledge that is super-valuable about how to make a car in volume at a profit; and then the idiosyncrasies of EVs has its own set of knowledge. That’s where Tesla, Karma and Workhorse come in.

There’s two big tasks we’re working on. The production team is racing to reconfigure a plant, and that’s a bit of a balance. We want to make 20,000 vehicles our first year, not 400,000, but we don’t want to shrink it down so much that when we’re at 400,000 we say to ourselves, “Boy, I wish we didn’t take that line out.” We think we struck the right balance there. Then reconfiguring, retooling. We’re making our body panels and everything that we need for our vehicle, but at the same time, we have a Detroit office that is doing all the engineering, the regulatory, the crash testing, the airbags and everything it takes to bring a modern vehicle to fruition. Kind of two parallel efforts that hopefully meet up at the same time when we start making vehicles.

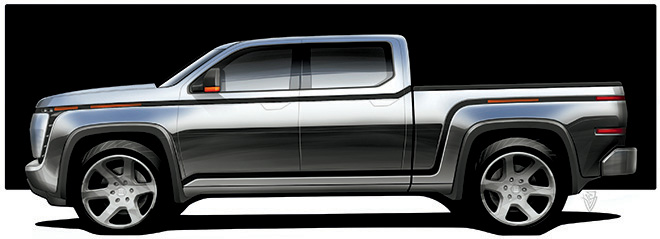

Charged: In terms of vehicle design, can you talk to me about the stage that you’re at now? Are you still evaluating fundamental different designs, or is that locked down?

Steve Burns: At this stage it’s locked down. Effectively, what we decided early on was that a lot of the parts of a pickup truck have been refined over 100 years. Remember, these are top-selling vehicles, both to fleets and consumers. The bed, the cab, the ergonomics of how people sit in it, that has really been refined nicely. We decided not to change that, because it’s a known science. We know how to build it. We’re trying not to reinvent anything we don’t have to reinvent.

As a polar opposite of that, for the Tesla Cybertruck, they decided to reinvent the body and the interior. That was a bridge too far for us, and since we sell to commercial fleets that tend to be rather conservative, we just wanted it to look like a cool new vehicle that you could differentiate from a gasoline pickup truck, but essentially when you looked at it you said, “That’s a pickup truck.” So the bed and ergonomics, and even inside, the armrests, cup holders and USB jacks and all that, we were riding on that known science. That really made it faster and less expensive to get to market.

We focused all our innovation on what’s different about us and hitting a price point. There are a lot of companies that are trying to out-Tesla Tesla, trying to build a very fast, high-end sedan. Sure, new technology typically hits the luxury market first, but we decided the technology is mature enough, and, especially the way we’re doing it with a super-simple design, we can come out for the middle market right away. Fleets buy on total cost of ownership. It has to pencil out. Everybody wants to be green, everybody would like a safer vehicle, everybody would like all these things, but if it doesn’t pencil out, it’s really a hard sell. We had to hit a certain price point to make those curves.

If somebody leases our truck versus leasing the least expensive gasoline truck they can find, we are a lot less expensive when you add your monthly lease payment, your gas for the month and your maintenance for the month. Right out of the gate, first month, the fleet is making money. That’s pretty compelling. But to hit that price point and not start in luxury and move downstream, we said, “We’ve got to make this puppy light so that it can go 250 miles. We can have the minimal pack size, and we have to really minimize the parts in the vehicle.” Hub motors lend themselves to very quick assembly, there’s a lot fewer parts, and the fleets appreciate that out in the field—there’s less to break. You’re never going to have a U-joint or a drive axle, you don’t have to worry about any of that stuff. That’s a big reason for why we’re using these hub motors. They also turned out to be the best handling and the safest, but it all started with the price point.

Charged: You’re shooting for $52,500 as your initial upfront cost?

Steve Burns: Yes, and we’re making sure we qualify for the $7,500 tax rebate, so most fleets will get it for $45,000.

Charged: Are you considering having more than one model? Different-size battery packs or any other options?

Steve Burns: Yeah, but in year one, we’re locked down to one vehicle, one cab. We picked the most popular configuration of pickup trucks for fleets, and that is the crew cab. You got a big back seat and the appropriate size bed. There’s basically one trim package as well. We just picked the sweet spot of what has been selling in fleet pickup trucks. We have to come out at the price point, and we’re racing to be first, because first mover advantage is strong and there’s a lot of pent-up demand. More options would make that more difficult, but we think there are plenty of people who will buy this initial model. And then we will come out with different cabs. You can have no back seats, smaller backseat, different bed lengths. We will start the configurations after the first year, but the first year is just locked down to maniacally focus on this one vehicle. We’ve got to hit it out of the park with the first one.

Charged: When will you unveil the production version?

Steve Burns: We’re planning to show the first vehicles in this summer. So, right now in the background, we’re building 30 vehicles for validation. That will all happen over the summer. Then we iterate, and we’re expecting to get through that cleanly, but there’ll be some changes. We’re starting production in December, pending final regulatory approval. If we have to, we can stockpile them for a few months while we’re waiting for regulators, but we’re planning to start production in December.

Charged: Are there any suppliers of the EV drivetrain components that you can talk about? Anyone that you’re partnering with on the motors or the batteries?

Steve Burns: We’re going to announce our motors partners soon. You can imagine, for hub motors, there’s just not a lot of suppliers. We worked with an existing hub motor company to tweak the design for our purposes, and we’re going to license that now that we’ve proved it out. We’re building the line inside of our plant for building the motor—we’re going to build the motors in America, in Lordstown.

Charged: You going to completely build them from scratch? Assemble the rotors and the stators?

Steve Burns: Yes, winding and everything. Just to control supply and quality and price. And we have a lot of the robots already. We’re going to repurpose those. Similarly, we’re buying our cells, but we’re building our own battery pack line. We’re designing our own battery packs. We worked with a third-party company on the BMS design and then licensed it, similar to the motors. We’re going to announce all those partners soon.

Charged: The electric utility FirstEnergy has placed the first order to buy 250 Endurance electric pickup trucks from Lordstown. There were also a lot of reservations for Workhorse’s pickup truck. Do you still see interest from those fleets?

Steve Burns: Yes, Workhorse had 6,000 pre orders for the W-15, and we’ve touched base with a few of those big order holders. That was across 19 fleets. We expect most of those to switch over to Endurance orders.

Charged: What you think is the best application for the Endurance commercially? Who do you think will be the first customers?

Steve Burns: Well of course the utility companies—they have a lot of pickup trucks, and they make electricity for a living, so it seems like their vehicles should be electric. They are aggressive. We just got a letter of intent from Clean Fuels Ohio to help deploy 500 Lordstown Endurances. We expect orders from a lot of the Clean Cities, a lot of the municipalities. In California, municipalities are only allowed to buy electric. If they want a truck, we will be the only choice for a while. But we get a lot of landscapers with Ford trucks, and florists. Any fleet that stays local lends itself to this. We think it’s going to be a great police car. I treat a police force as a local fleet. Police cars idle a lot, just to keep all their electronics going—obviously there won’t be any idling with us.

There’s been a lot of startups that didn’t get to market in this space. A lot of them get to the point where they have a vehicle, but how are they going to make it? We’re starting with a plant already, which is really powerful. We have really been fortunate to attract so many high-end automotive production and design engineers. But if somebody said, “What’s the secret sauce? Why is this different?” There’s no other hub motor vehicle in production.

A lot of people say, “What’s a hub motor?” and you say, “Well, you see all the electric bikes and electric scooters, those are all hubs.” People can kind of extrapolate that we’ve got four big ones of those in there. We tell fleets: buy it for the economics, but we also intend this to be the safest pickup truck you can put your people in. Best handling, lowest rollover rate, and of course, zero emissions. We’re really trying to make it the best truck they can buy, not just the most economical.

This article appeared in Charged Issue 48 – March/April 2020 – Subscribe now.