“The name Rodrigo Ronconi corresponds to the truth,” says Rodrigo Ronconi, without unlocking his gaze from the data sheet of one very problematic Diablo. “Otherwise there is no truth,” he finishes, looking up through tortoise-shell spectacles.

Righteous words, but Ronconi is not an arrogant man. At least, he doesn’t seem arrogant in the three minutes I’ve known him. He seems industrious, very passionate and, frankly, like he could do without our surprise visit, although he hides it well. His Diablo issue is trivial but, at the same time, not. The owner needs part of the body repainted and wants it done yesterday. Tracking down the code for this ‘unique’ hue so it can be mixed afresh in Milan, and at great expense, has pitched Ronconi onto the trail of two Diablos from the early 1990s. The £160,000 question is: which one exhibits the correct paint code for our beleaguered owner?

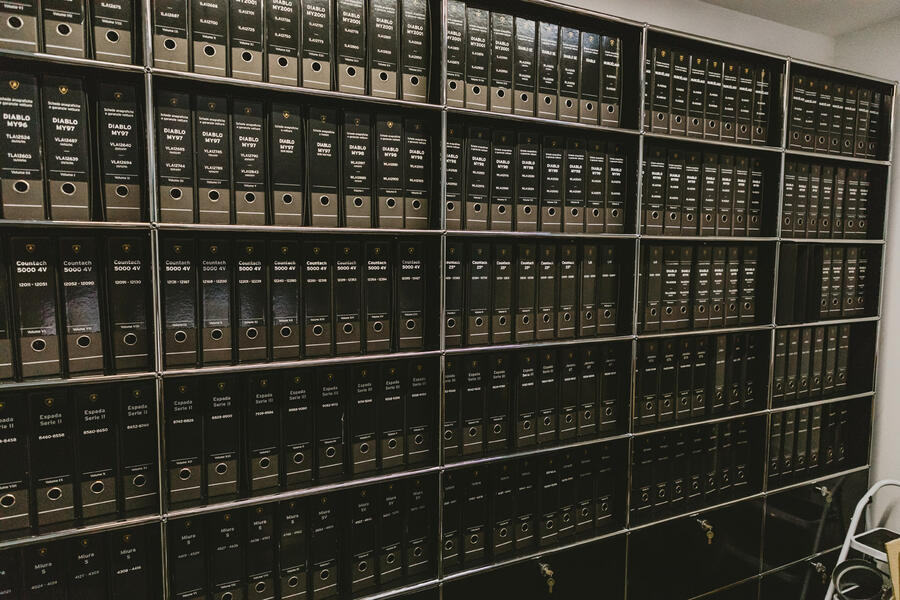

As an archivist at Lamborghini’s Polo Storico department, this is Ronconi’s bread and butter. Time pressure, attention to detail, plenty of cash on the line. All the storied brands now have enterprises that service, restore, promote and authenticate their diasporas of heritage scattered around the globe, and Lamborghini is no different. The market for classics is worth around £1.78 billion annually (enough to buy every Porsche 911 2.7 RS in existence almost twice over) and so there is money to be made, but Lamborghini also seems to have strong altruistic inclinations.

The marque is still young and some of the existing staff were inducted in the 1980s or even the ’70s, not long after Ferruccio and Enzo fell out. Now is therefore the time to begin preserving the brand’s history and exploit the pool of lived experience before it dries up. Lamborghini is now so serious that it even consulted Porsche Classic, masters in the field of conservation, for advice when it established Polo Storico in 2015.

It remains a relatively small operation, not only because the department is younger than the Aventador but also due to the relative scarcity of Miuras, Countachs, Espadas and so on. Lamborghini built just 6900 cars between the initial 350 GT of 1964 and the very last Diablo in 2001, which is nothing. By comparison, Ferrari made around 60,000 cars during the same period and, by Lamborghini’s own admission, the internal library of photos and records at Maranello is astonishing in its depth. Jaguar, meanwhile, built 67,000 E-Types alone between 1961 and 1975.