The idea that a rookie team could arrive at the Le Mans 24 Hours with an entirely new car and end up in contention for a place on the podium may seem fanciful. However, that is exactly what Scuderia Cameron Glickenhaus (SCG) did with its SCG 007 Hypercar. The eponymously named outfit is the brainchild of owner James Glickenhaus, a film producer and devout collector of historic endurance racing icons. His and the team’s journey to Le Mans began 15 years ago with construction of the P4/5 by Pininfarina, a one-off, Ferrari Enzo-based road car created through a collaboration with the Italian styling house in 2006, with Ferrari’s blessing. That car morphed into the racing P4/5 Competizione, which competed at the Nürburgring 24h in 2011 and 2012, followed by SCG’s first cars built on a bespoke chassis, the SCG 003 and 004, both of which also raced successfully on the Nordschleife in the SP-X class. Glickenhaus has always professed a desire to enter Le Mans and the FIA’s Le Mans Hypercar (LMH) regulations provided him the opportunity to do just that and compete (albeit as an outside bet) for overall honors.

Starting from scratch

Starting from scratch

‘) } // –>

‘) } else { console.log (‘nompuad’); document.write(‘

‘) } // –>

Though technically a US team, SCG has a long-standing relationship with Italian outfit Podium Advanced Technologies, which designed and developed both the 003 and 004 GT cars and would also take on responsibility for constructing the 007 Hypercars. In a shrewd move, Glickenhaus and Podium recognized they did not have the expertise to go it alone and signed up a trio of high-caliber development partners for the Le Mans assault. Endurance stalwart Joest Racing, out of contract with Mazda in the IMSA DPi class, provides trackside operations; Sauber Group was contracted to run the aero program; and Pipo Moteurs was tasked with designing a bespoke engine.

Despite a highly compressed development schedule and the plethora of challenges involved in building an all-new car, SCG made it work. Unlike Toyota, SCG did not have an existing LMP1 as a starting point for its Hypercar design. However, according to Luca Ciancetti, SCG team principal and head of both Podium’s motorsport and automotive engineering businesses, the biggest problem was not creating a chassis, but sourcing the powertrain. “When we started, one of the main issues was finding an engine, because in the beginning, the power level was much higher than what we have now,” he says, referencing the first Hypercar ruleset released in 2019, which placed peak power at 580kW (784bhp).

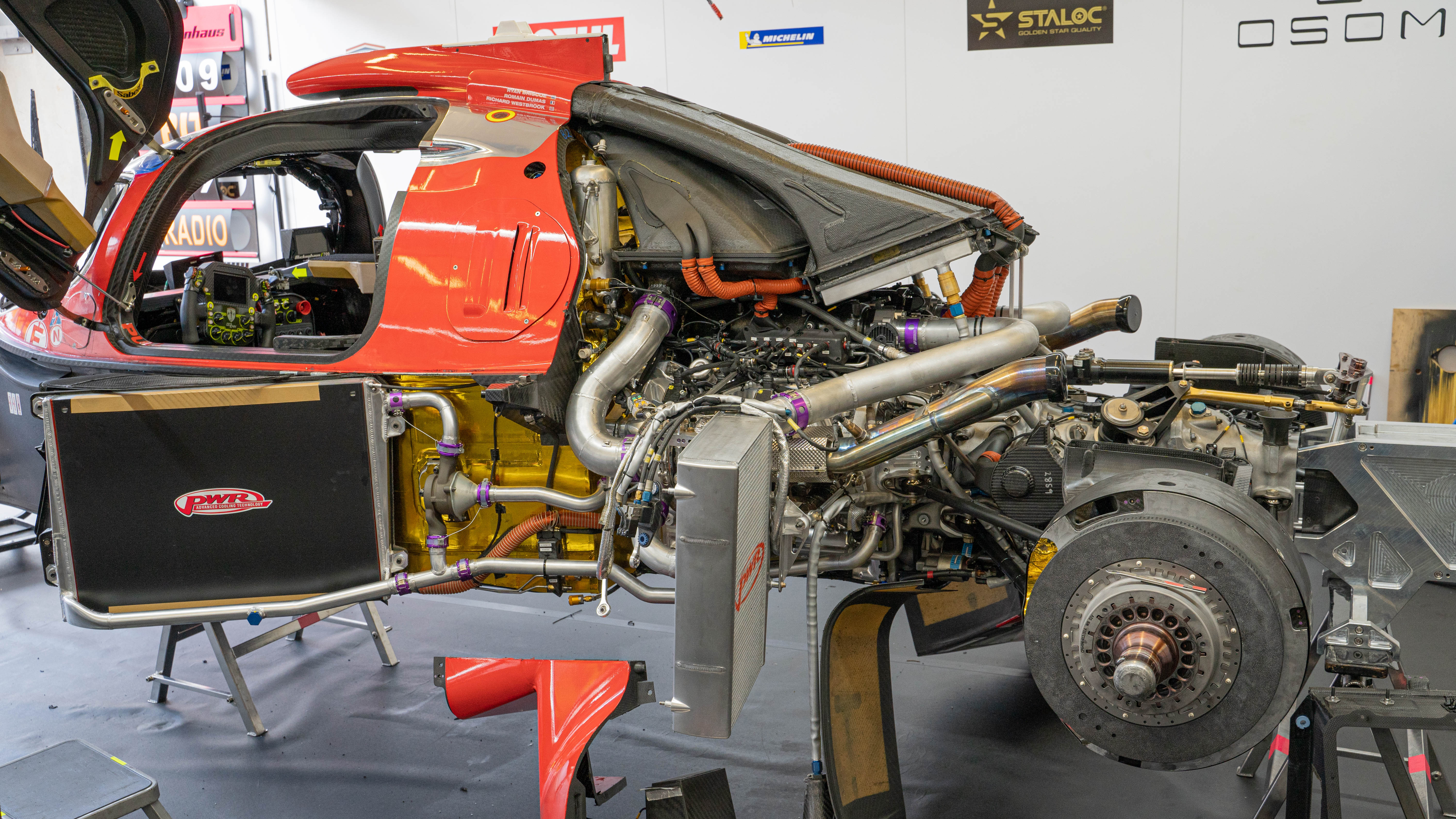

“The reality was there was nothing available, which is why we decided to go for a new development with Pipo. That was one of the first decisions we had to make, because it is such a big part of the car,” he recounts. Podium had no existing relationship with the French engine builder, and the latter had never built an endurance race engine. It is better known for its rallying products, which have equipped the likes of Hyundai and M-Sport’s WRC efforts. Regardless, as Ciancetti explains, “They had the I4, which was capable of good performance and reliability, so we decided to do a development program to mirror that [design]along a common crank [to create a V8].”

The resulting 3.5-liter V8 uses the block and cylinder head technology from the rally engines. Given the I4 WRC motors produce approximately 400bhp and cover thousands of kilometers between rebuilds, by doubling up the top end architecture and detuning it (considerably in the end) it had the makings of an ideal endurance engine package. Ciancetti has been impressed with the engine’s seemingly bulletproof reliability and notes that the synergy between Pipo and the SCG/Podium organizations was excellent thanks to both being “two small companies trying to do the best they can while working very hard.”

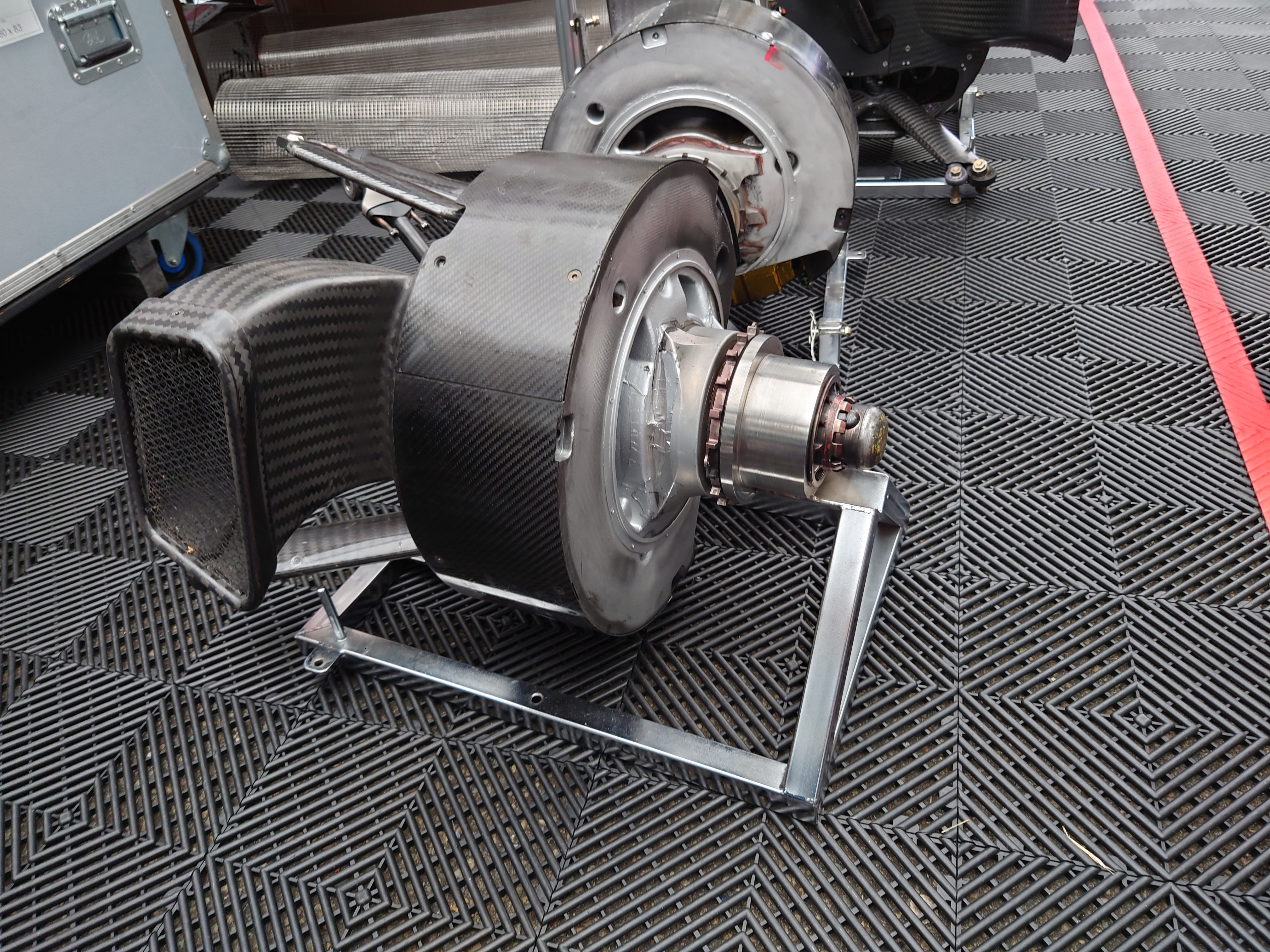

The team opted to use Xtrac for the transmission supply, which was able to provide an almost off-the-shelf gearbox solution. As with the engine package, says Ciancetti, reliability was the order of the day; however, Xtrac’s standard transverse LMP gearbox still had to be validated for use in Hypercar. “We had to run some extra structural checks because the cars are very heavy, to make sure the crash loads could be sustained by the transmission,” he says. The transmission is fitted with a shift system supplied by Mega-Line, again selected for its well-proven reliability. As was the case for Toyota, Ciancetti reveals that the lateness of certain rule changes could not be taken advantage of. “Some of the [key]components had already been released when the rules changed, and we did not have time or resources to update everything. Some areas of the car, for example, could be lighter but we are around 1,030kg. We would be happier if we could carry a bit more ballast, but the weight distribution of the car is the one we designed for and it is working quite well.”

Styling exercise

The SCG 007 is undeniably attractive (particularly when compared with the last crop of LMP1 machines) and James Glickenhaus was adamant the car had to measure up aesthetically. Ciancetti recalls, “The initial shape of the car was directly sketched by Jim and that was the starting input for the aero guys. Jim was adamant that he wanted a cool car, and the aero department was definitely very open-minded to keep it as close as possible to what he envisaged. “Fortunately, though the requirement [regarding aero performance]of the rules is challenging, it is not quite as challenging as it used to be, so we were able to accept some styling guidelines as a starting point. We then had to make up our minds where we wanted to be in terms of other areas of the rules; for example, the size and volume of the crash structures.”

Team technical director Luca Ciancetti

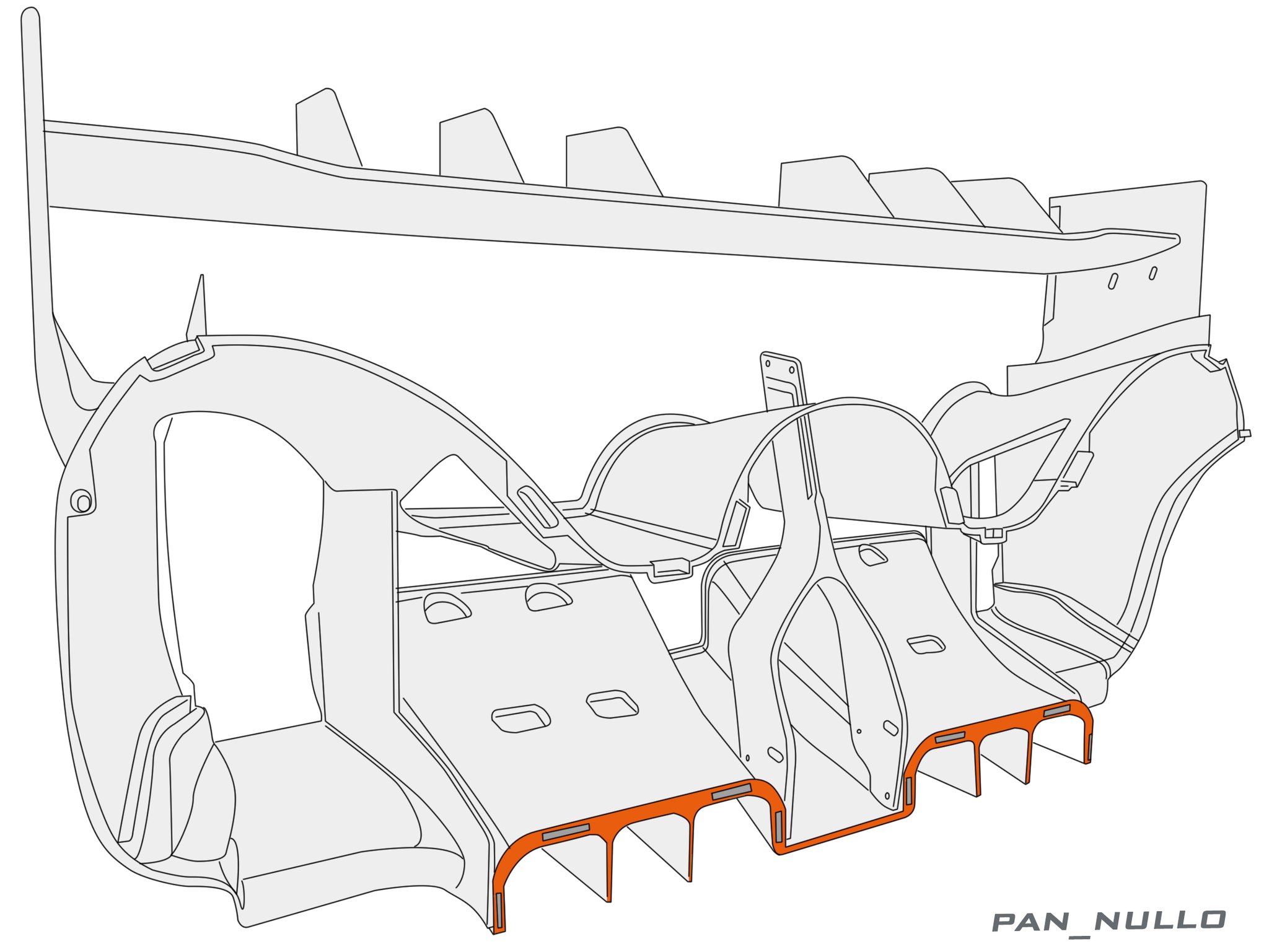

On this last point, both the front and rear crash structures were built to the maximum dimensions permitted by the regulations, ostensibly so that when it came to crash testing sufficient margin of error remained to account for any shortcomings in the team’s finite element analysis (FEA) calculations. This and other aspects of the overall design philosophy were, says Ciancetti, all intended to reduce problems once parts were released for manufacture. “We tried to figure out a comprehensive pre-concept for the car and reduce the risk on the final product,” he explains.

The freedom afforded by the balance of performance-based (BoP) Hypercar rules also forced Podium to revise its approach to the design process. Ciancetti says, “It is definitely a different philosophy because you are generally used to geometry constraints in the rules. Because this is a regulation set based on performance, you must move your mind to work with the huge design freedom you have in terms of shapes and materials, while keeping in mind that whatever you do must match the maximum performance allowed.” Illustrating the scope of this creative freedom, one of the striking elements of the 007’s bodywork is the rear wing, replete as it is with a series of strakes along its upper surface. The Hypercar rules removed the specific requirement for a dorsal ‘fin’ as seen on previous LMP1 machinery. Instead they only demand a set level of lateral stability be achieved, opening the potential for a more imaginative approach. Ciancetti remarks, “In order to [hit the targets]properly we had to add some vertical fins and looked at a number of different solutions; this one worked very well and Jim liked it a lot.”

Competition reality

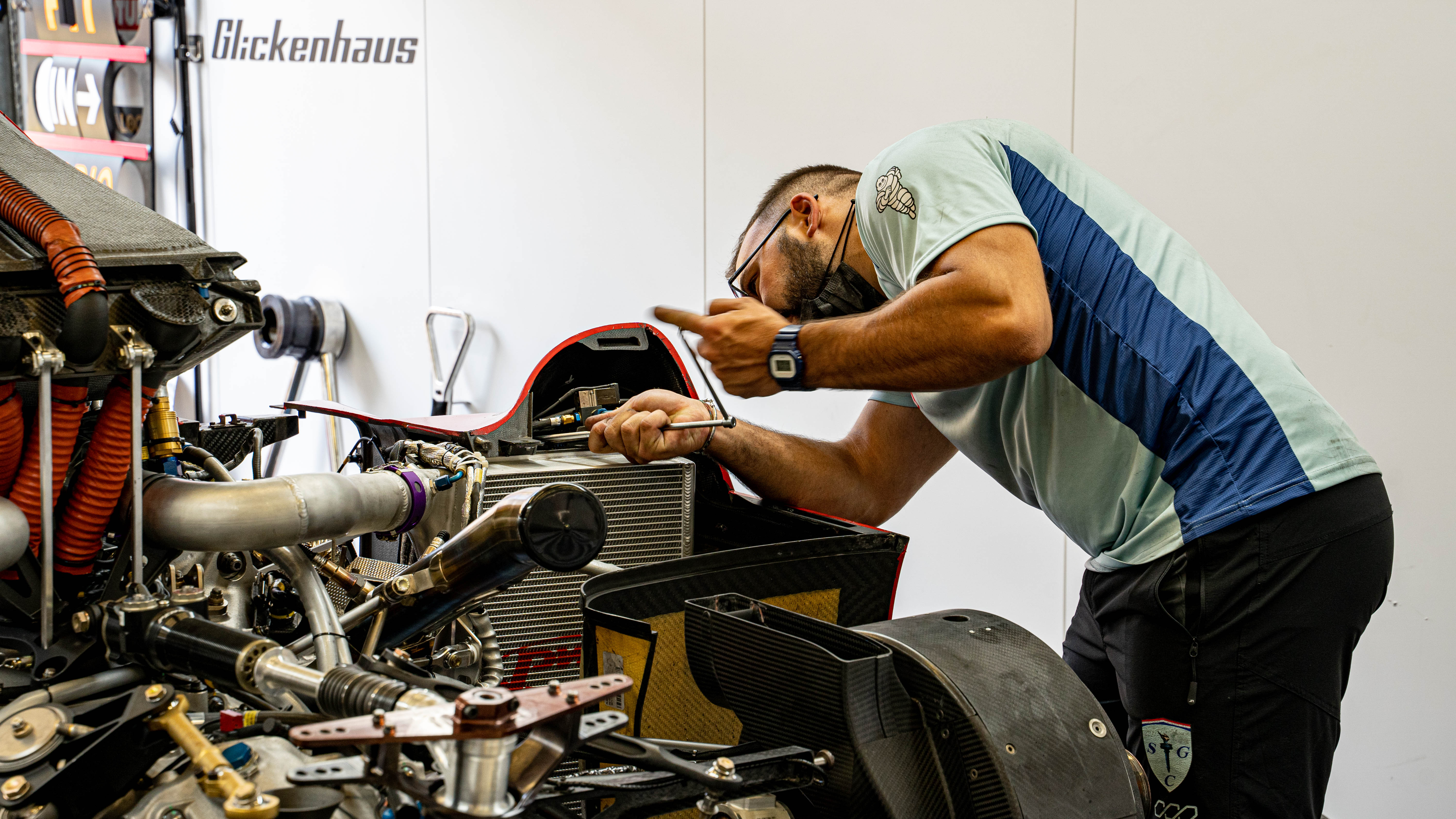

No matter how much faith the team placed in the BoP process, Ciancetti is pragmatic about the fact that SCG was competing against the firepower of established manufacturer Toyota, and a well-proven car in the shape of the grandfathered Alpine LMP1. “If you want to properly manage a program like this, you cannot imagine that because the performance is balanced, it is the same for all teams and budgets,” he muses. “You have to manage your budget in the best way you can, to achieve the best results.” This, he points out, means that areas not governed by the BoP constraints must be executed to perfection. For example, “Reliability becomes even more important. You can get some help from the rules from a performance point of view, but you will never get any from a reliability perspective. You need a car that is at the right performance level, reliable, simple, easy to swap parts on if you have an issue during the race.”

On the subject of serviceability, the Italian says design targets were built in from the start of the project, but it soon became apparent that other areas of the car needed attention once it made its competition debut. For example, based on its running pre-Le Mans, the team expected to experience issues with brake wear. As such, the brake cooling arrangement and caliper/disc change drills were honed. Ciancetti states, “Areas like brake cooling are quite hard to simulate properly, so we had to make some revisions. We got the changes down to 1 min 30.”

However, come the main event, neither SCG 007s suffered any brake woes. There was also some doubt coming into the Le Mans race as to whether the team would be able to triple stint its Michelin tires. “We worked a lot in the time between the [Le Mans] test and now to understand the tire and there is quite a difference in performance as we move between [ambient]conditions,” Ciancetti says. “We have found that we are quite strong when the window is well defined; if it is very cold or very hot, we have a good setup. The middle of the window is a bit trickier for us, it is harder to manage the transition.” Fortunately for SCG, it was able to get on top of wear issues it had experienced earlier in the WEC season, particularly on the rears, which Ciancetti suggests was more due to “the way we were using the car rather than the product”.

Ultimately, SCG achieved what many thought would be impossible: excluding a first lap clash between the #708 and the #8 Toyota, both cars ran almost faultless races at Le Mans, albeit with the #709 never able to match the pace of its sister car. The former was even in contention for a podium place but in the end couldn’t quite match Alpine. James Glickenhaus was upbeat about the car’s performance; however, he cautioned that even for a privateer of substantial means, his continued participation in the WEC beyond 2021 is far from assured and hinges on both customer car sales and bringing more sponsors on board. With the arrival of a swathe of new manufacturers in Hypercar from 2022, Glickenhaus’s best opportunity for a podium at the French classic may have passed, but hopefully conditions will prove favorable for the class’s only privateer to remain.