The end of the era of the internal combustion engine has been heralded. The national environment ministers of the European Union met on Wednesday night agreed on it, from 2035 only new cars without CO2 emissions will be allowed. However, they agreed on exceptions: combustion engines powered by synthetic fuels may continue to be placed on the market.

The decision, which was largely initiated by Germany, lags behind the more radical demands of the EU Parliament. That had previously decided on a complete ban on combustion engines. But even so it is a cut. “I have every confidence that the European car industry can pull it off,” Frans Timmermans, 61, the Commission Vice-President, told ministers as heated talks in Brussels drew to a close. “Our car manufacturers are among the leading companies in Europe and can remain so if they embrace this global change.”

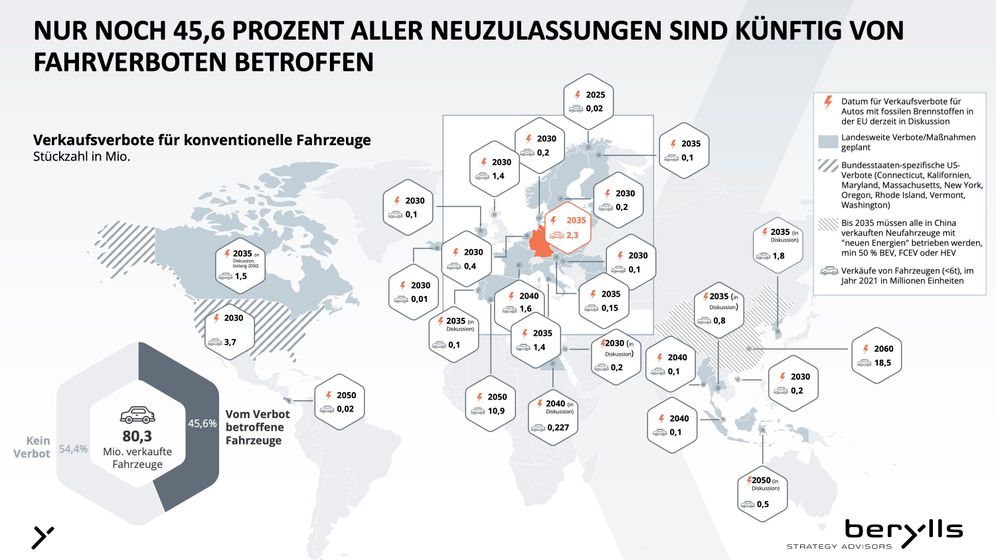

Petrol and diesel engines still clearly dominate. According to the consulting firm Berylls, around 80.3 million combustion engines were sold worldwide in 2021. The announced bans reduce the potential market enormously. “If the sales or registration bans announced worldwide for vehicles with internal combustion engines were to apply today, 36.6 million units or 45.6 percent of the current global sales volume would be affected,” says Andreas Radics, Managing Partner at the Berylls Group. China enters this equation with 18.5 million combustion engines sold in 2021 alone.

So what does the virtual end of combustion engines in Europe mean for the auto industry? The most important questions and answers at a glance.

What exactly have the EU countries decided?

The EU states agreed that the so-called fleet limits for cars should be reduced to zero by 2035. These specify to car manufacturers how much CO2 the vehicles they produce may emit during operation. As a result, new petrol and diesel vehicles sold are likely to be progressively replaced by electric vehicles to meet the targets.

At Germany’s insistence, the decision leaves a back door open for internal combustion engines. The EU Commission should examine whether there could be exceptions for combustion engines if they are operated with synthetic fuels. Such e-fuels are produced using electricity; if it comes from renewable energies, they too can be climate-neutral. However, it is unclear whether they will ever become marketable.

Who is under pressure from the proposal?

The unification of the EU countries primarily requires car manufacturers such as bmw and Porsche under pressure who continue to rely on alternatives to pure electromobility. BMW CEO Oliver Zipse (58), for example, still believes in the combustion engine and thinks a ban from 2035 is wrong. “To put everything on one card these days is an industrial policy mistake,” he said before the agreement on Tuesday. The path to climate neutrality should also be created in a way that is open to technology. According to Zipse, it is still unclear whether the necessary charging infrastructure for e-cars can be built by 2035. It is also unclear how Europe wants to ensure access to the crucial raw materials for all electric cars. New dependencies threatened here.

In addition to successful electric models such as the Taycan, Porsche boss Oliver Blume (53) continues to rely on combustion engines for the 911, for example. He also invested in the development of synthetic fuels and has thus taken a special path within the VW Group. In Chile, the sports car manufacturer invested around half a billion euros in the construction of a plant for the production of e-fuels. However, according to current plans, the substances should only be mixed with conventional petrol. Everything else is “science fiction,” a spokesman told SPIEGEL on Wednesday.

The German Association of the Automotive Industry (VDA) is also skeptical. “A Europe-wide, reliable charging infrastructure is a mandatory requirement for consumers,” said a VDA spokesman. In Germany one is far away from that.

The shares of Mercedes-Benz, Volkswagen and BMW lost above average on Wednesday.

more on the subject

Who looks calmly at the agreement?

A number of car companies are already aiming for an earlier end to the combustion engine. Volkswagen intends to stop selling new petrol and diesel vehicles from 2035 anyway. Group boss Herbert Diess (63) is therefore relaxed in view of the ban from 2035: “It can come – we are best prepared,” he told employees on Tuesday.

Also Audi, ford, Mercedes, Opel and Volvo no longer want to build combustion engines from 2030. At the world climate conference in Glasgow in November, some car manufacturers, including Mercedes and Ford, aggressively called for a ban on sales of combustion engines in the leading markets from 2035. The Mercedes board of directors expressly welcomed the move by the EU Parliament. “By 2030, we are ready to go fully electric wherever market conditions allow,” said the group’s head of external relations, Eckart von Klaeden (56).

Which markets will remain for the automotive industry after 2035?

Outside the EU, too, many countries have now planned bans on the registration and sale of combustion engines or specifically diesel. There are particularly long transitional regulations in China. In the largest car market in the world, a strict sales ban will only apply from 2060. The island of Hainan alone, where 200,000 combustion engines were sold in 2021, has already imposed a sales ban on combustion engines from 2030. In China, 18.5 million combustion engines were sold in 2021. Also in the Autonation United States the ban is still a long way off. In some states, the phase-out of combustion engines is not planned until 2050. 3.7 million vehicles would be affected.

Enlarge image

The groups could therefore still sell combustion cars in important markets even after a de facto ban in Europe. But at least the European manufacturers will hardly base their strategy on this.

Which countries want to phase out before 2035?

Some countries have had an exit date for some time: Norway for example, from 2025 onwards, it no longer wants to allow the sale of vehicles with classic petrol or diesel engines. Great Britain, Sweden, Denmark, the Netherlands and Belgium most recently aimed for the year 2030.

When do the decisions apply?

The decisions of the environment ministers still have to be approved by the Commission and the European Parliament. However, it is considered likely that there will be hardly any significant changes, since the resolutions are based on proposals from the Commission and deliberations in the EU Parliament were partly taken into account. The final agreement is expected by the end of the year.